CHAPTER XIII

JACK RATTENBURY

Jack Rattenbury, nicknamed Rob Roy of the West (1778, in Beer, Devon – 1844) was an English smuggler.

WE do not expect of smugglers that they should be either literary or devout. The doings of the Hawkhurst Gang, and of other desperate and bloody-minded associations of free-traders, seem more in key with the business than either the sitting at a desk, nibbling a pen and rolling a frenzied eye, in search of a telling phrase, or the singing of Methodist psalms. Yet we have, in the “Memoirs of a Smuggler,” published at Sidmouth in 1837, the career of Jack Rattenbury, smuggler, of Beer, in Devonshire, told by himself; and in the diary of Henry Carter, of Prussia Cove, and later of Rinsey, we have learned how he found peace and walked with the saints, after a not uneventful career in robbing the King’s Revenue of a goodly portion of its dues as by law enacted. With the eminent Mr. Henry Carter and his interesting brothers we have already dealt, reserving this chapter for the still more eminent Rattenbury, “commonly called,” as he says on his own title-page (in the manner of one who knows his own worth), “The Rob Roy of the West.”

THE SMUGGLERS

We need not be so simple as to suppose that Rattenbury himself actually wrote, with his own hand, this interesting account of his adventures. The son of a village cobbler in South Devon, born in 1778, and taking to a seafaring life when nine years of age, would scarce be capable, in years of eld, of writing the conventionally “elegant” English of which his “Autobiography” is composed. But nothing” transpires” (as the actual writer of the book might say) as to whom Rattenbury recounted his moving tale, or by whose hand it was really set down. Bating, however, the conventional language, the book has the unmistakable forthright first-hand character of a personal narrative.

Before the future smuggler was born, as he tells us, his shoemaker, or cobbler, father disappeared from Beer in a manner in those days not unusual. He went on board a man-o’-war, and was never again heard of. Whether he actually “went,” or was taken by a pressgang, we are left to conjecture. But they were sturdy, self-reliant people in those days, and Mrs. Rattenbury earned a livelihood in this bereavement by selling fish, ” without receiving the least assistance from the parish, or any of her friends.”

When Jack Rattenbury was nine years of age he was introduced to the sea by means of his uncle’s fishing-boat, but dropped the family connection upon being lustily rope’s-ended by the uncle, as a reward for losing the boat’s rudder. He then went apprentice to a Brixham fisherman, but, being the younger among several apprentices, was accordingly bullied, and left; returning to Beer, where he found his uncle busily engaging a privateer’s crew, war having again broken out between England and France, and merchantmen being a likely prey.

So behold our bold privateer setting forth, keen for loot and distinction; the hearts of men and boys alike beating high in hope of such glory as might attach to capturing some defenceless trader, and in anticipation of the prize-money to be obtained by robbing him. But see the irony of the gods in their high heavens! After seven weeks’ fruitless and expensive cruising at sea, they espied a likely vessel, and bore down upon her, with the horrible result that she proved to be an armed Frenchman of twenty-six guns, who promptly captured the privateer, without even the pretence of a fight: the privateering crew being sent, ironed, down below hatches aboard the Frenchman, which then set sail for Bordeaux. There those more or less gallant souls were flung into prison, whence Rattenbury managed to escape to an American ship lying in the harbour. It continued to lie there, in consequence of an embargo upon all shipping, for twelve months: an anxious time for the boy. At last, the interdict being removed, they sailed, and Rattenbury landed at New York. From that port he returned to France in another American ship, landing at Havre; and at last, after a variety of transhipments, came home again to Beer, by way of Guernsey.

EARLY ADVENTURES

He was by this time about sixteen years of age. For six months he remained at home engaged in fishing; but this he found a very dull occupation after his late roving life, and, as smuggling was then very active in the neighborhood, and promised both profit and excitement, he accordingly engaged in a small vessel that plied between Lyme Regis and the Channel Islands, chiefly in the cognac-smuggling business. This interlude likewise soon came to an end, and he then joined a small vessel called The Friends, lying at Bridport. On his first voyage, in the entirely honest business of sailing to Tenby for a cargo of culm, this ship was unlucky enough to be captured by a French privateer; but Rattenbury escaped by a clever ruse, off Swanage, and, swimming ashore, secured the intervention of the Nancy, revenue cutter, which recaptured The Friends, and brought her into Cowes that same night: a very smart piece of work, as will be readily conceded. Those were times of quick and surprising changes, and Rattenbury had not been again aboard The Friends more than two days when he was forcibly enlisted in the Navy, by the pressgang. Escaping from the more or less glorious service of his country at the end of a fortnight, he then prudently went on a long cod-fishing cruise off Newfoundland; but on the return voyage the ship was captured by a Spanish privateer and taken to Vigo. Escaping thence, he again reached home, to be captured by the bright eyes of one of the buxom maids of Beer, where he was married, April 17th, 1801, proceeding then to live at Lyme Regis. Privateering to the west coast of Africa then occupied his activities for a time, but that business was never a profitable one, as far as Rattenbury was concerned, and they caught nothing; but, on the other hand, were nearly impressed, ship and ship’s company too, by the Alert, King’s cutter. Piloting, rather than privateering, then engaged his attention, and it was while occupied in that trade that he was again impressed and again escaped.

He then returned to Beer, and embarked upon a series of smuggling ventures, varied by attempts on the part of the pressgang to lay hold of him, and by some other (and always barren) privateering voyages. Ostensibly engaged in fishing, he landed many boat-loads of contraband at Beer, bringing them from quiet spots on the coasts of Dorset and Hampshire, where the goods had been hidden. Christchurch was one of these smugglers’ warehouses, and from the creeks of that flat shore he and his fellows brought many a load, in open boats. On one of these occasions he fell in with the Roebuck revenue tender, which chased and fired upon him: the man who fired doing the damage to himself, for the gun burst and blew off his arm. But Rattenbury and his companions were captured, and their boat-load of gin was impounded. Rattenbury surely was a very Puck among smugglers: a tricksy sprite, at once impudent and astonishingly fortunate. He hid himself in the bottom of the enemy’s own boat, and by some magical dexterity escaped when it touched shore: while his companions were held prisoners. Nay, more. When night was come, he was impudent enough, and successful enough, to go and release his friends, and at the same time to bring away three of the captured gin-kegs. In that same winter of 1805 he made seven trips in a new-built smuggling vessel. Five of these were successful ventures, and two were failures.

In the spring of 1806 his crew and cargo of spirit-tubs were captured, on returning from Alderney, by the Duke of York cutter. He was taken to Dartmouth, and, with his companions, fined £100, and given the alternative of imprisonment or serving aboard a man-o’-war. After a very short, experience of gaol, they chose to serve their country, chiefly because it was much easier to desert that service than to break prison; and they were then shipped in Dartmouth roads, whence Rattenbury escaped from the navy tender while the officers were all drunk; coming ashore in a fisherman’s boat, and thence making his way home by walking and riding horseback to Brixham, and from that port by fishing-smack.

SCRIMMAGE AND FLIGHT

Soon after this adventure he purchased a share in a galley, and, with some companions, made several successful trips in the cognac smuggling between Beer and Alderney. At last the galley was lost in a storm, and in rowing an open boat across Channel Rattenbury and another were captured by the Humber sloop, and taken for trial to Falmouth and committed to Bodmin gaol, to which they were consigned in two post-chaises, in company with two constables. Travelers were thirsty folk in those days, and at every inn between Falmouth and Bodmin the chaises were halted, so that the constables could refresh themselves. Evening was come before they had reached Bodmin, and while the now half-seas-over constables were taking another dram at the lonely wayside inn called the “Indian Queens,” Rattenbury and his companions conspired to escape. Behold them, then, when ordered by the constables to resume their places, refusing, and entering into a desperate struggle with those officers of the law. A pistol was fired, the shot passing close to Rattenbury’s head. He and his companion then downed the constables and escaped across the moors; where, meeting with another party of smugglers, they were sheltered at Newquay. Next morning they travelled horseback, in company with the host who had sheltered them, to Mevagissey, whence they hired a boat to Budleigh Salterton, and thence walked home again to Beer.

Next year Rattenbury was appointed captain of a smuggling vessel called the Trafalgar, and after five fortunate voyages had the misfortune to lose her in heavy weather off Alderney. He and some associates then bought a vessel called the Lively, but she was chased by a French privateer and the helmsman shot. The privateer’s captain was so overcome by this incidental killing that he relinquished his prize. After a few more trips, the Lively proved unseaworthy, and the confederates then purchased the Neptune, which was wrecked after three successful voyages had been made. But Rattenbury tells us, with some pride, that he saved the cargo. In the meanwhile, however, the Lively having been repaired, had put to sea in the smuggling interest again, and had been captured and confiscated by the revenue officers. Rattenbury lost £160 by that business. Soon afterwards he took a share in a twelve-oared galley, and was one of those who went in it to Alderney for a cargo. On the return they were unfortunate’ enough to fall in with two revenue cutters: the Stork and the Swallow, that had been especially detailed to capture them; and accordingly did execute that commission, in as thorough and workmanlike fashion as possible, seizing the tubs and securing the persons of Rattenbury and two others; although the nine other oarsmen escaped. Captain Emys, of the Stork, took Rattenbury aboard his vessel, and treated him well, inviting him to his cabin and to eat and drink with him. Next day the smugglers were landed at Cowes.

“Rattenbury,” said the genial captain, “I am going to send you aboard a man-o’-war, and you must get clear how you can.” To this the saucy Rattenbury replied, “Sir, you have been giving me roast meat ever since I have been aboard, and now you have run the spit into me.” He was then put aboard the Royal William, on which he found a great many other smuggler prisoners. Thence, in the course of a fortnight, he and the others were drafted to the Resistance frigate, and sent to Cork. Arrived there, our slippery Rattenbury duly escaped in course of the following day, and was home again in six days more.

UNPATRIOTIC

The activities of the smugglers were at times exceedingly unpatriotic, in other ways than merely cheating the Revenue, and Rattenbury was no whit better than his fellows. He had not long returned home when he made arrangements, for the substantial consideration of one hundred pounds, to embark across the Channel four French officers, prisoners of war, who had escaped from captivity at Tiverton. Receiving them on arrival at Beer, and concealing them in a house near the beach, their presence was soon detected and warrants were issued for the arrest of Rattenbury and five others concerned. Rattenbury adopted the safest course and surrendered voluntarily, and was acquitted, with a magisterial caution not to do it again.

Every now and again Rattenbury found himself arrested, or in danger of being arrested, as a deserter from the Navy. Returning on one of many occasions from a successful smuggling trip to Alderney, and drinking at an inn, he found himself in company with a sergeant and several privates of the South Devon Militia. Presently the sergeant, advancing towards him, said, “You are my prisoner. You are a deserter, and must go along with me.”

Must! what meaning was there in that imperative word for the bold smuggler of old? None. But Rattenbury’s first method was suavity, especially as the militia had armed themselves with swords and muskets, and as such weapons are exceptionally dangerous things in the hands of militiamen. “Sergeant,” said he (or says his author for him, in that English which surely Rattenbury himself never employed) “you are surely laboring under an error. I have done nothing that can authorise you in taking me up, or detaining me; you must certainly have mistaken me for some other person.”

He then describes how he drew the sergeant into a parley, and how, in course of it, he jumped into the cellar, and, throwing off jacket and shirt, to prevent anyone holding him, armed himself with a reaphook (sickle) and bade defiance to all who should attempt to take him.

The situation was relieved at last by the artful women of Beer rushing in with an entirely fictitious story of a shipwreck and attracting the soldiers’ attention. In midst of this diversion, Rattenbury jumped out, and, dashing down to the beach, got aboard his vessel. After this incident he kept out of Beer as much as possible; and shortly afterwards was successful in piloting the Linskill transport through a storm that was likely to have wrecked her, and so safely into the Solent. He earned twenty guineas by this; and received the advice of the captain to get a handbill printed, detailing the circumstances of this service, by way of set-off against the various desertions for which he was liable to be at any time called to account.

RIDICULOUS RATTENBURY

Soon after this, Lord and Lady Rolle visited Beer, and Rattenbury’s wife took occasion to present his lordship with one of the bills that had been struck off. “I am sorry,” observed Lord Rolle, reading it, “that I cannot do anything for your husband, as I am told he was the man who threatened to cut my sergeant’s guts out.” Such, you see, was the execution Rattenbury, at bay in the cellar, had proposed with his reaphook upon the military.

Hearing this, and learning that Lady Rolle was also in the village, he ran after her, and overtaking her carriage, fell upon his knees and presented one of his handbills, entreating her ladyship to use her influence on his behalf, so that the authorities might not be allowed to take him. It is a ridiculous picture, but Rattenbury makes no shame in presenting it. “She then said,” he tells us, “you ought to go back on board a man-o’-war, and be equal to Lord Nelson; you have such spirits for fighting. If you do so, you may depend I will take care you shall not be hurt.” To which he replied; “My lady, I have ever had an aversion to [sic] the Navy. I wish to remain with my wife and family, and to support them in a creditable manner,*) and therefore can never think of returning.”

*) By smuggling, presumably.

Her ladyship then said, “I will consider about it,” and turned off. About a week afterwards, the soldiers were ordered away from Beer, through the influence of her ladyship, as I conjecture, and the humanity of Lord Rolle.

And so Rattenbury was left in peace. He tells us that he would have now entered upon a new course of life, but found himself “engaged in difficulties from which I was unable to escape, and bound by a chain of circumstances whose links I was unable to break. … I seriously resolved to abandon the trade of smuggling; to take a public-house, and to employ my leisure hours in fishing, etc. At first the house appeared to answer pretty well, but after being in it for two years, I found that I was considerably gone back in the world; for that my circumstances, instead of improving, were daily getting worse, for all the money I could get by fishing and piloting went to the brewer.” Thus, he says, he was obliged to return to smuggling; but we cannot help suspecting that Rattenbury is here not quite honest with us, and that smuggling offered just that alluring admixture of gain and adventure he found himself incapable of resisting.

RETURN TO SMUGGLING

Adventures, it has been truly said, are to the adventurous; and Rattenbury’s career offered no exception to the rule. There was, perhaps, never so unlucky a smuggler as he. Returning to the trade in November 1812, and returning with a cargo of spirits from Alderney, his vessel fell in with the brig Catherine, and was pursued, heavily fired upon, and finally captured. The captain of the Catherine, raging at them, declared they should all be sent aboard a man-o’-war; but a search of the smuggling craft revealed nothing except one solitary pint of gin in a bottle: the cargo having presumably been put over the side. The crew were, however, taken prisoners aboard the Catherine, and their vessel was taken to Brixham. Rattenbury and his men were kept aboard the Catherine for a week, cruising in the Channel, and then the brig put in again to Brixham, where the wives of the prisoners were anxiously waiting. Next morning, in the absence of the captain and chief officer ashore, the women came off in a boat, and were helped aboard the brig; when Rattenbury and three of his men jumped into the boat and pushed off. The second mate, who was in charge of the vessel, caught hold of the oar Rattenbury was using, and broke the blade of it, and the smuggler then threw the remaining part at him. The mate then fired; whereupon Rattenbury’s wife knocked the firearm out of his hand. Picking it up, he fired again, but the boat’s sail was up, and the fugitives were well on the way to shore, and made good their escape, amid a shower of bullets. They then dispersed, two of them being afterwards re-taken and sent aboard a man-o’-war bound for the West Indies; but Rattenbury made his way safely home again and was presently joined there by his wife.

The public-house was closed in November 1813, smuggling was for a time in a bad way, owing to the Channel being closely patrolled; and Rattenbury, now with a wife and four children, made but a scanty subsistence on fishing and a little piloting. In September 1814 he ventured again in the smuggling way, making a successful run to and from Cherbourg, but in November another run was quite spoilt, in the first instance by a gale, which obliged the smugglers to sink their kegs, and in the second by the revenue officers seizing the boats. Finally, on the next day a custom-house boat ran over their buoy marking the spot where the kegs had been sunk, and seized them all-over a hundred. “This,” says Rattenbury, with the conciseness of a resigned victim, “was a severe loss.”

The succeeding years were more fortunate for him. In 1816 he bought the sloop Elizabeth and Kitty, cheap, having been awarded a substantial sum as salvage, for having rescued her when deserted by her crew; and all that year did very well in smuggling spirits from Cherbourg. Successes and failures, arrests, escapes, or releases, then followed in plentiful succession until the close of 1825, when the most serious happening of his adventurous career occurred. He was captured off Dawlish, on December 18th, returning from a smuggling expedition, and detained at Budleigh Salterton watch-house until January 2nd, when he was taken before the magistrates at Exeter, and committed to gaol. There he remained until April 5th, 1827. In 1829 he says he “made an application” to Lord Rolle, who gave him a letter to the Admiral at Portsmouth, and went aboard the Tartar cutter. In January 1830 he took his discharge, received his pay at the custom-house, and went home.

Very slyly does he withhold from us the subject of that application, and the nature of the Tartar’s commission; and it is left for us to discover that the bold smuggler had taken service at last with the revenue and customs authorities, and for a time placed his knowledge of the ins and outs of smuggling at the command of those whose duty it was to defeat the free-traders. It was perhaps the discovery that the work of spying and betraying was irksome, or perhaps the ready threats of his old associates, that caused him to relinquish the work.

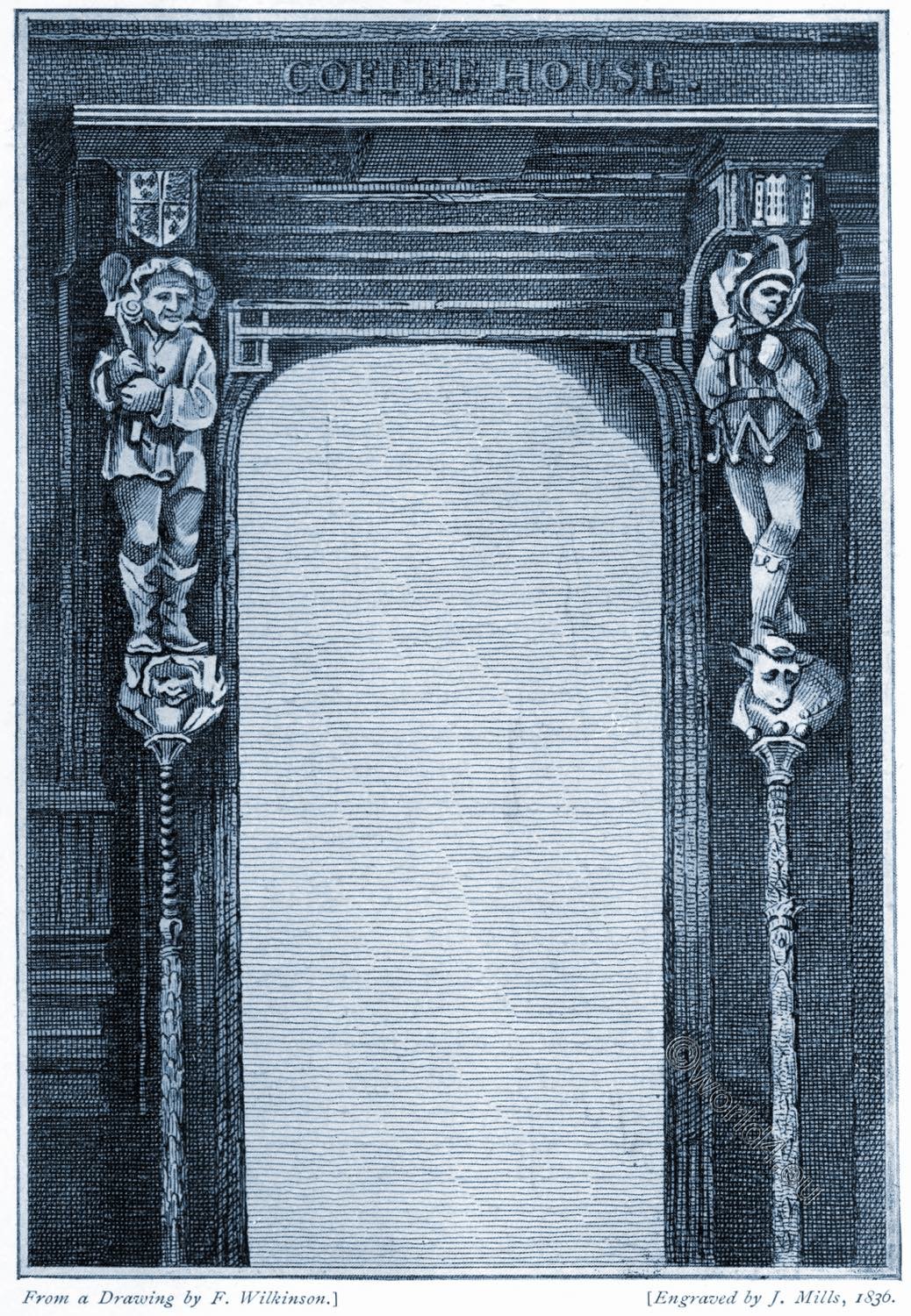

The door way of King John’s Tavern. The statues at the doorway which were well executed appear to have represented a porter or sergeant at mace and a clown or domestic fool. Above the head of the former was a shield of the royal arms of France and England, quarterly; and over that of the latter a shield charged with a castle the armorial ensign of city of Exeter.

However that may be, he was soon at smuggling again, carried on in between genuine trading enterprises; and in November 1831 was unlucky enough to be chased and captured by the Beer preventive boat. As usual, the cargo was carefully sunk before the capture was actually made, and although the preventive men strenuously grappled for it, they found nothing but a piece of rope, about one fathom long. On the very slight presumptive evidence of that length of rope, Rattenbury and his eldest son and two men were found guilty on their trial at Lyme Regis, and were committed to Dorchester gaol. There they remained until February 1833.

Rattenbury’s last smuggling experience was a shore going one, in the month of January 1836, at Torquay, where he was engaged with another man in carting a load of twenty tubs of brandy. They had got about a mile out of Newton Abbot, at ten o’clock at night, when a party of riding officers came up and seized the consignment “in the King’s name.” Rattenbury escaped, being as eel-like and evasive as ever, but his companion was arrested.

Thus, before he was quite fifty-eight years of age, he quitted an exceptionally checkered career; but his wonted fires lived in his son, who continued the tradition, even though the great days of smuggling were by now done.

That son was charged, at Exeter Assizes, in March 1836, with having on the night of December 1st, 1835, taken part with others in assaulting two custom-house officers at Budleigh Salterton. Numerous witnesses swore to his having been at Beer that night, sixteen miles away, but he was found guilty and sentenced to seven years’ transportation; the Court being quite used to this abundant evidence, and quite convinced, Bible oaths to the contrary notwithstanding, that he was at Budleigh Salterton, and did in fact take part in maltreating His Majesty’s officers.

LAST APPEARANCE

Jack Rattenbury was on this occasion crossexamined by the celebrated Mr. Serjeant Bompas, in which he declared he had brought up that son in a proper way, and “larnt him the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments.” (Perhaps also that important Eleventh Commandment, “Thou shalt not be found out!”)

“You don’t find there, ‘Thou shalt not smuggle?'” asked Mr. Serjeant Bompas.

“No,” replied Rattenbury the ready, “but I find there, ‘Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.’ “

The injured innocent, like to be transported for his country’s good, was granted a Royal Pardon, as the result of several petitions sent to Lord John Russell.

The village of Beer, deep down in one of the most romantic rocky coves of South Devon, is nowadays a very different kind of place from what it was in Rattenbury’s time. Then the home of fishermen daring alike in fishing and in smuggling, a village to which strangers came but rarely, it is now very much of a favorite seaside resort, and full of boarding-houses that have almost entirely abolished the ancient thatched cottages. A few of these yet linger on, together with one or two of the curious old stone water conduits and some stretches of the primitive cobbled pavements, but they will not long survive. The sole characteristic industry of Beer that is left, besides the fishing and the stone-quarrying that has been in progress from the very earliest times, is the lace-making, nowadays experiencing a revival.

But the knowing ones will show you still the smugglers’ caves: deep crannies in the chalk cliffs of Beer, that at this place so curiously alternate with the more characteristic red sandstone of South Devon.

Source:

- The smugglers; picturesque chapters in the story of an ancient craft by Charles George Harper. London, Chapman & Hall, ltd. 1909.

- Memorials of old Devonshire by Frederick John Snell. London, Bemrose 1904.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.