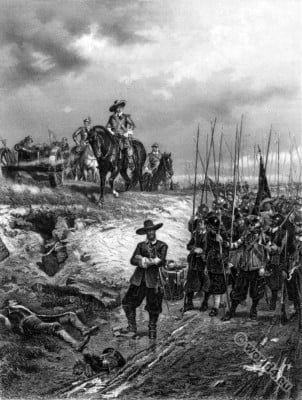

The Battle of Marston Moor.

The Battle of Marston Moor was held on 2 July 1644 near York and was one of the decisive battles of the English Civil War. In her the army of Parliament won his first major victory over the royalists. Northern England was thus lost for the royalists of King Charles I.

The two parties had been for many months engaged in a warfare in which success and defeat so equally alternated that it was difficult to ascertain on which side lay the balance of advantage. That such should have been the result of the contest speaks highly for the courage and discipline of the Cavaliers, for from the very first the strength and resources of the rivals were most unequally divided.

The Parliament commanded London and all the seaports except Newcastle. Through the influence of the Earl of Northumberland, lord high admiral, the entire dominion of the sea was in the hands of the Houses. All the magazines of arms and ammunition were, at the outset of the civil war, seized by the Parliament, whilst the right of levying taxes—a host of strength in itself—could be exercised with profit only by the assembly.

Charles, on the other hand, was deprived of much that his enemies possessed. His revenue had been taken by the Parliament, and he was thus forced to rely on the wealth and generosity of his adherents, and on the taxes levied in the counties that declared for him. He was in supplied with artillery and ammunition, and in order to arm his followers was even compelled to borrow the weapons of the trained bands. The one grand advantage he possessed, and it was an advantage that stood him in good stead in the early part of the war, was in the nature and quality of his troops.

In a conflict between patrician and proletarian it was confidently expected that men drawn from the aristocracy, the landed gentry,and the yeomanry, would prove themselves superior to an army comprised of the rabble of the multitude – the “the poor tapsters” and “town apprentice people,” as Oliver Cromwell called them. Nor were these expectations at first falsified.

The Royalists were victorious at Edgehill; they had reduced Cornwall to submission; at Stratton and at Roundaway Down the troops of Lord Stamford and Sir William Waller were defeated; the great Hampden had perished at Chalgrove Field, an irreparable loss to the Parliament; and Bristol, the second city in the kingdom, had been surrendered by Nathaniel Fiennes with such pusillanimity, that it nearly cost its cowardly defender his head.

The war had not lasted a year, and the advantage was not with the Parliament. Instead, however,of following up his successes by at once marching on London, then in a state of consternation and approaching disaffection, Charles wasted his time by attacking Gloucester. This city was the only remaining garrison in the west possessed by the Parliament, and once reduced, the king held the whole course of the Severn under his command.

The siege was resolutely undertaken by the Royalists, and as resolutely sustained by the defenders. But the gallant city was not to be left long unaided. The progress of the king’s arms, the defeat of Waller, the taking of Bristol, and now the siege of Gloucester, had excited the fears and the indignation of the Parliament. Every effort, it was felt, must at once be made to prevent any further triumphs of the Royalists. Fourteen thousand men were instantly marched westward, and the king was forced to raise the siege.

The battle of Newbury followed. The result was indecisive, and Charles lost on the field his valued friend and faithful adherent Lucius Cary, Viscount Falkland. In the north the Royalists were defeated at Wakefield and at Gainsborough, but shortly afterwards were compensated for these reverses by the total rout of Fairfax at Atherton Moor.

A union with Scotland, however, at this time, gave additional increase to the power of the Parliament, and the Solemn League and Covenant* had been signed at Edinburgh.

Twenty thousand Scottish troops poured into England, and the popular party soon began to acquire ascendency, while the energies of the Parliament were devoted to bring the contest to an issue. In the eastern association fourteen thousand men were levied under the Earl of Manchester seconded by Cromwell, while nearly twenty thousand men under Essex and Waller were assembled in the neighbourhood of London.

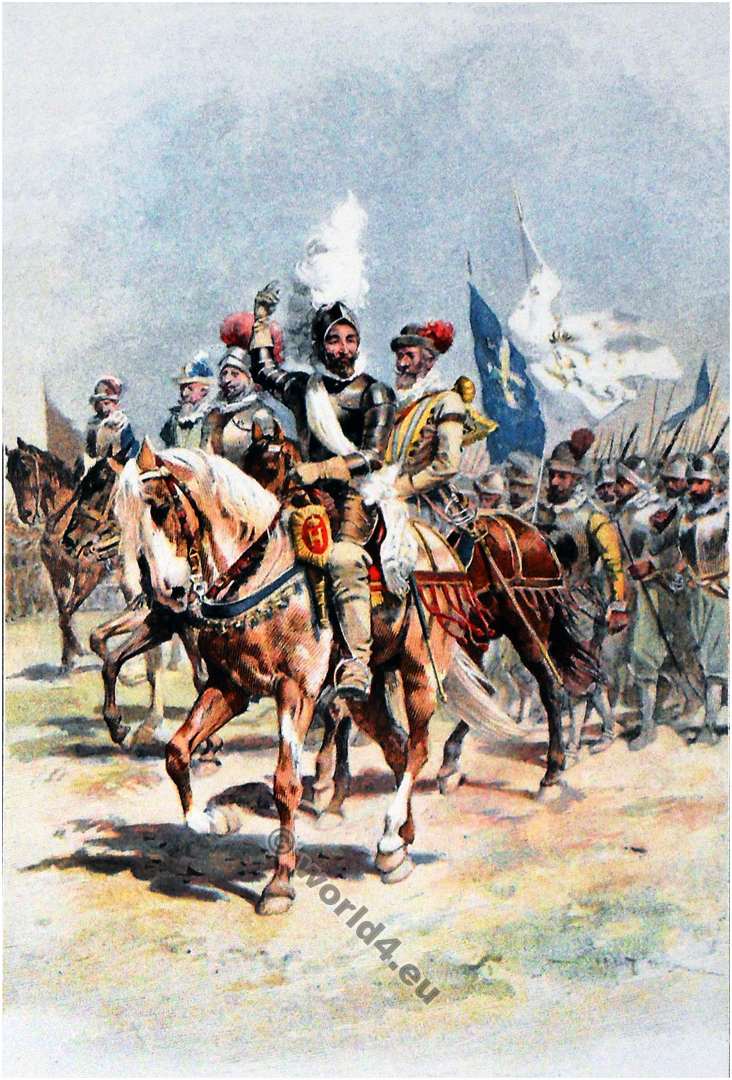

The troops of Essex were to march against the king, while those of Waller were to attack Prince Maurice in the west. The utmost efforts of Charles were barely sufficient to raise ten thousand men. Lincoln had been taken by the Earl of Manchester, whose army now uniting with that of Lords Leven and Fairfax was closely besieging York, then vigorously defended by the Marquis of Newcastle. On a sudden the besiegers were surprised by Prince Rupert.

The forces of the Parliament hastily raised the siege, and drawing themselves up on Marston Moor prepared to give battle to the Royalists. An engagement was now inevitable. After a night spent in anxious repose both armies prepared for action. A large ditch ran in front of a portion of the Parliamentarian force.

Their centre was under the command of Lords Fairfax and Leven. On the right Sir Thomas Fairfax was stationed; Cromwell and Manchester held the left, which was a barren was teending in a moor. The royal forces under Prince Rupert took up their position opposite to Sir Thomas Fairfax, while Cromwell and Manchester on the left were opposed by Goring’s cavalry and several infantry brigades.

At seven in the evening the battle commenced. Manchester’s infantry moved upon the ditch,but whilst endeavouring to form they were mowed down like ripened grain before the murderous fire of the Royalists. Goring now ventured to take advantage of this opportunity and charged with his cavalry,but ere he could advance for that purpose Cromwell wheeled round the right of the ditch and fell full upon his flank.

The right wing of the Royalists essayed to resist, but in vain; they were broken, routed, and fled in every direction. “Colonel Sydney,” says the Parliamentary Chronicle, “son to the Earl of Leicester, charged with much gallantry at the head of my Lord of Manchester’s regiment of horse, and came off with many wounds, the true badge of his honour.” It is also stated that on this occasion, after Sydney had been dangerously wounded and was within the enemy’s power, a soldier stepped out of the ranks of Cromwell’s regiment and rescued him from his dangerous position.

Sydney naturally desired to know the name of his preserver; but the soldier, with that uncouth magnanimity which characterized the men who fought under Cromwell, sternly replied that he had not saved him to obtain a reward, and returned to his place in the ranks without disclosing his name.

General Fairfax had been driven back under the impetuous charge of Rupert, and the prince, believing the day won, eagerly pursued his retreating foe. He had cause to repent his rashness. Whilst turning to break the centre of the Parliamentary force, and finish what he considered to be a complete victory, he suddenly encountered Cromwell, who had simultaneously charged and defeated the centre of the Royalists.

The shock was tremendous, but the result of the conflict was never for a moment doubtful. Prince Rupert was driven back with great loss, and victory declared decisively for the forces of the Parliament. “It was ten o’clock,” writes Mr. Forster in his Life of Cromwell, “and by the melancholy dusk which enveloped the moor might be seen a fearful sight.

Five thousand dead bodies of Englishmen lay heaped upon that fearful ground. The distinction which separated in life these sons of a common country seemed trifling now. The plumed helmet embraced the strong steel cap, as they rolled on the heath together, and the loose love-locks of the careless Cavalier lay drenched in the dark blood of the enthusiastic republican.”

Soon after the battle of Marston Moor York opened her gates, and a large part of the north of England submitted to the authority of the Parliament.

*) This covenant was received by the Parliament of the Assembly of Divines, September 25, 1643. According to Hallam it “consisted in a noath to be subscribed by all sorts of persons in both kingdoms, whereby they bound themselves to preserve the Reformed religion in the Church of Scotland, indoctrine, worship, discipline, and government,according to the Word of God and practice of the best Reformed churches; and to endeavour to bring the churches of God in the three kingdoms to the nearest conjunction and uniformity in religion, confession of faith, form of church government, directory for worship, and catechizing; to endeavour, without respect of persons, the extirpation of Popery, Prelacy (that is, church government by archbishops, bishops, their chancellors, and commissaries, deans and chapters, archdeacons, and all other ecclesiastical officers depending on that hierarchy), and whatsoever should be found contrary to sound doctrine and the power of godliness; to preserve the rights and privileges of the parliaments and the liberties of the kingdoms, and the king’s person and authority, in the preservation and defence of the true religion and liberties of the kingdoms; to endeavour the discovery of incendiaries and malignants, who hinder the reformation of religion, and divide the king from his people, that they may be brought to punishment; finally, to assist and defend all such as should enter into this covenant and not suffer themselves to be withdrawn from it, whether to revolt to the opposite party, or to give in to a detestable indifference or neutrality.” This document was signed by members of both houses, and by civil and military officers. A large number of the beneficed clergy, who refused to subscribe, were ejected.

Source: Pictures and Royal Portraits illustrative of English and Scottish History by Thomas Archer. London 1878.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.