Richard I the Lionheart 1157-1199.

Richard I in French Cœur de Lion, actually Richard Plantagenet; was from 1189 to his death King of England. From 1172 to the year of his coronation was Richard Duke of Aquitaine. Then he held the title of Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou. Richard was the third son of King Henry II. Of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine.

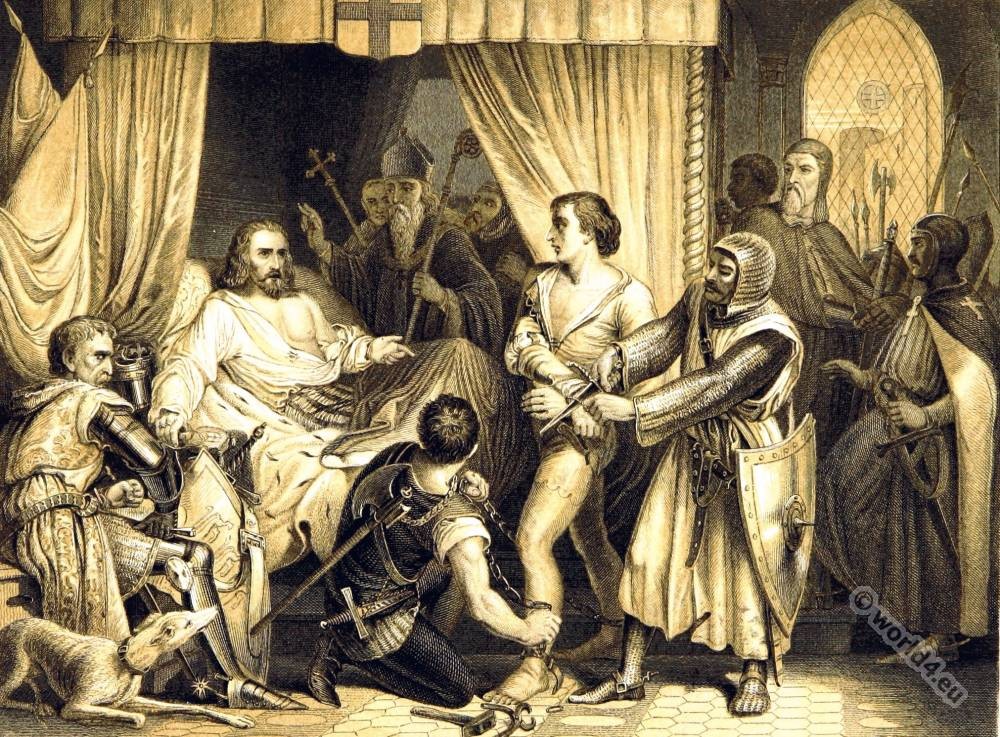

Bertran de Gurdun also known as Pierre Basile and John Sabroz. According to the legend Richard let Pierre Basile, the enemy’s skirmishers of the deadly bolt, looking after winning the battle and bring to him and knighted him with the words:

“Anyone who is capable to kill me, the King, it is worthy to be a knight.”

To what extent this is true, is no longer to be clarified. The facts speak against it, because the shooter was skinned after the death of Richard of his relatives and tortured to death.

THE LION-HEART.

In Richard of Aquitaine, or, as he was for some time called, of Poitou, there seemed to revive some of those personal qualities which were conspicuous in William the Conqueror. Henry II. had exhibited some thing of the statesmanship and the executive control which distinguished the first Norman ruler; and his son Richard, though he scarcely equalled him in administrative ability, yet possessed those personal qualifications which gave him an heroic aspect and signalized him as a leader of men; fitted alike by an imposing figure and by an undaunted courage to command those by whom he was surrounded. It is scarcely to be wondered at that, while Coeur de Lion is so prominent a figure in what may be called the romance of history, he is so differently regarded by various writers who discuss his character and influence.

While on the one hand he is represented as a Troubadour knight, speaking the language of Southern France and possessing the accomplishments of those poet-warriors of Aquitaine of whom he was the companion in arms,— he is on the other side represented as a fierce and ruthless conqueror delighting in battle and with a propensity to coarse and almost brutal indulgences.

There can be little doubt that he combined something of both characters— that while he exhibited the strong characteristics of the Vikings, from whom he could claim direct descent, his habits were greatly modified by the influences of early training and education as well as by the influence of his mother, the heiress of the land south of the Loire.

There was the commanding presence which overawed opposition, and seemed to stamp him as a natural leader of men; there was the chivalrous yet somewhat stern courtesy; there was the uncompromising pride; there was the adventurous spirit,in which the love of fame and the lawless greed of acquisition seemed to be blended in almost equal proportions; there was the devotion to a great purpose of an enthusiast, often distracted for a moment by the temptation of immediate adventure and gain, but using even these distractions as new instruments inits further prosecution; there was the thirst for battle, and the delight in the mere physical contest, and yet the common sense and shrewdness of perception which could see the limits of acquisition and of fame, and could turn away from fruitless laurels (Sanford’s Estimates ofEnglish Kings).

The vicissitudes which Richard I. suffered, and the treachery and cruelty of his enemies, never seemed to subdue his spirit; and though he sometimes made severe reprisals, he was not wanting in an impulsive and noble generosity. As an example of his unconquerable courage may be cited the boldness with which, after enduring sickness and a long imprisonment in the castle of Tiernsteign, where the base and cowardly Henry, emperor of Germany, loaded him with chains, he maintained his cause by frank and noble speech in presence of the council before which he was brought, proudly declaring that as King of England none there had a right to call him to account, but flinging back the foul charges brought against him.

His revenge was, it is true, shown by the refusal to release the Bishop of Beauvais, a relative of the French king and one of Richard’s bitterest enemies, who was taken prisoner while fighting in complete armour by Marchadee, the leader of the Brabanters, who was in Richard’s service during the long war with Philip of France.

The king ordered him to be loaded with irons and imprisoned in the Castle of Rouen. When two of the bishop’s chaplains waited on Richard to ask for milder treatment for their master, he answered them by saying, “You yourself shall judge whether I am not justified. This man has done me many wrongs. Much I could forget, but not this. When in the hands of the emperor, and when, in consideration of my royal character, they were beginning to treat me more gently and with some marks of respect, your master arrived, and I soon experienced the effects of his visit; overnight he spoke with the emperor, and in the morning a chain was put upon me such as a horse could hardly bear.”

The bishop afterwards implored the intercession of the pope (Clementine), who, however, upbraiding him with his departure from canonical rules, consented only to ask for mercy as a friend and refused to interfere as pope. He wrote to Richard, however, requesting him to pity his son the bishop; to which entreaty the king responded, by sending to the pontiff the blood-stained coat of mail which the bishop wore when he was taken prisoner, with a scroll attached to it inscribed with the words, “This have we found, know now whether it be thy son’s coat or no.”

The ready and noble generosity of Coeur de Lion may be illustrated by his prompt forgiveness (at the intercession of his mother Eleanor) of his despicable brother John, who had done all he could to ruin and supplant him. There was perhaps something a little contemptuous, however, in his remark: “I forgive him, and hope I shall as easily forget his injuries as he will forget my pardon.” It is scarcely to be wondered at that this bold frank man should have exacted from his equally chivalrous foes an admiration which in some instances led them to regard him with a kind of loyal friendship.

There can be no doubt that he and Saladin, the accomplished and warlike chief of the Saracens, respected each other; and we can scarcely wonder that the battle of Jaffa should have made the English king famous both among friends and foes. Deserted by the French and Germans under their treacherous leaders, Richard had fallen back upon Acre, and Saladin, ever vigilant, at once came down from the mountains of Judea and took Jaffa all but the citadel. The king immediately ordered his few stanch troops to march by land to its relief, while he and a small retinue of knights took seven vessels and hastened to make the journey by sea.

On arriving in the roadstead they found the beach occupied in force by the enemy; but rejecting the advice of his companions, Richard at once leaped into the water, exclaiming, “Cursed for ever be he that followeth me not.” There was enough force in that great stalwart frame and strong arm to represent half-a-dozen ordinary men, and one and all sprang after him with a shout and a fierce onslaught that dispersed the best of the Saracens and retook the town.

The next day Saladin appeared with the main body of his army, and Richard’s troops had also arrived though they were greatly inferior in number. Here was an occasion when as general and leader Coeur de Lion made up for the want of a more numerous army. His dispositions were so well ordered, his personal valour so conspicuous, that victory was the result. Every champion who met Richard that day was dismounted, and his untiring arm smote on till nightfall.

The generous admiration of Saphadin the brother of Saladin was so moved that when the king’s charger was killed he sent him two magnificent horses as a present. There was something wildly chivalrous about the feeling of these warriors towards each other. Every time that Coeur de Lion headed the charge the Saracens broke and fled. No wonder that his name became a word of fear among the Mussulmans and of fame amongst friends and enemies alike.

Tall above the middle height, but more remarkable for his broad chest and strong yet pliant sinews, he was by general confession physically the strongest of living men of his time, and he was also the least accessible to fear and the most self-confident in his strength.

Strange that after all, this great warrior should be slain by an arrow from a rebel among his Poictevin vassals. For some time a ballad had been known to exist in Normandy, the burden of which was that Limousin the arrow was making by which the tyrant would die; but this, perhaps, was common during the reign of Henry also, for he was shot at more than once by these disaffected men of the south.

The exact occasion of Richard’s death-wound is perhaps uncertain, but the most fully accredited account is that it was during a visit to Vidomar, Viscount of Limoges, who had found a treasure, and refusing to give up the due share to Richard as his lord, was being besieged by the king in his castle of Châlus.

Richard, with Marchadee, the captain of his Brabant mercenaries, was viewing the stronghold to see where a breach might best be effected, when a youth named Bertrand de Gurdun recognized him from the ramparts, and at once discharged an arrow which entered the king’s shoulder. Soon after, the castle was taken by assault, and the wound, which was not in itself very dangerous, had been made mortal by unskilful attempts to extract the arrow head. Bertrand de Gurdun, who was among the few of those who remained alive after the victory, was brought before Richard.

“Wretch” said the king, “what harm have i done to thee that thou shouldst seek my life?” to which the man made answer, “You slew my father and my two brothers with your own hand, and you had intended now to kill me; therefore take any revenge on me that you may think fit, for I will readily endure the greatest torments so long as you have met with your end after having inflicted evils so many and so great upon the world.” “Youth, I forgive thee,” cried Richard; “loose his chains and give him a hundred shillings;” but the youth stood before the king, and with scowling features and undaunted neck did his courage demand the sword.

“Live on,” said Richard, “although thou art unwilling, and by my bounty behold the light of day. To the conquered faction now let there be bright hopes and the example of myself.” Richard was frequently addicted to gross and sensual indulgence, but his fits of penitence seem to have been sincere; and he had a real respect for religion, though he did not always forbear jesting with the clergy, and making shrewd and pungent speeches at their expense. Indeed his wit was caustic, and his ability as a serious lampooner was an accomplishment which properly belonged to him as a poet knight of Languedoc.

Perhaps the most remarkable instance of it was his retort to the bishop, who, coming to visit him on his death-bed, and being asked by the king what he should do, replied, “Consider of disposing of thy daughters in marriage and do penance.” This confirms what I said before,” said the king, “that you are jesting with me, for you know that I never had either daughters or sons.” “Of a truth, O King,” rejoined the bishop, “you have three daughters, and have had and nourished them long; for as your firstborn daughter you have Pride; as your second, Covetousness; as your third, Self-indulgence. These you have had and have loved out of all reason from your very youth.”

“True, it is,” said the king, “that I have had these, and thus it is that I will bestow them in marriage. My first-born, Pride, I give to the Templars (The Crusades. The Knights Templar.), who are swollen with insolence and puffed up beyond all others. My second, that is Covetousness, I give to the Gray Friars, who with their covetousness molest all their neighbours like mad devils. My last, however, namely, Self-indulgence, I make over to the Black Friars, who devour roast meat and fried, and are never satiated.”

A strange contention this at the death-bed of a king, but not out of keeping with a time which has grown almost as unfamiliar to many of us as that of which we read when we take up the history of Greece or Rome. Richard of the Lion-Heart was a great man—of an English pattern, however. Not without some of the diplomacy of his father Henry, but with more warlike ability and robust physical force. He was only forty-two years old when he died, after reigning ten years, all of which were years of strife.

His body was carried to Fontevraud, where it was buried at the feet of his father. His heart was deposited in two caskets of lead and deposited in the Cathedral at Rouen, where it was discovered “withered to the semblance of a faded leaf” on the 31st July, 1838. It was then in a cavity in the lateral wall near the effigy which was hidden beneath the pavement of the choir. The thin leaf of silver which had inclosed the heart in the inner casket was rudely inscribed,

+ Hie Jacet : Cor : Ricar. di : Regis : Anglorum :

Source: Pictures and Royal Portraits illustrative of English and Scottish History by Thomas Archer. London 1878.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.