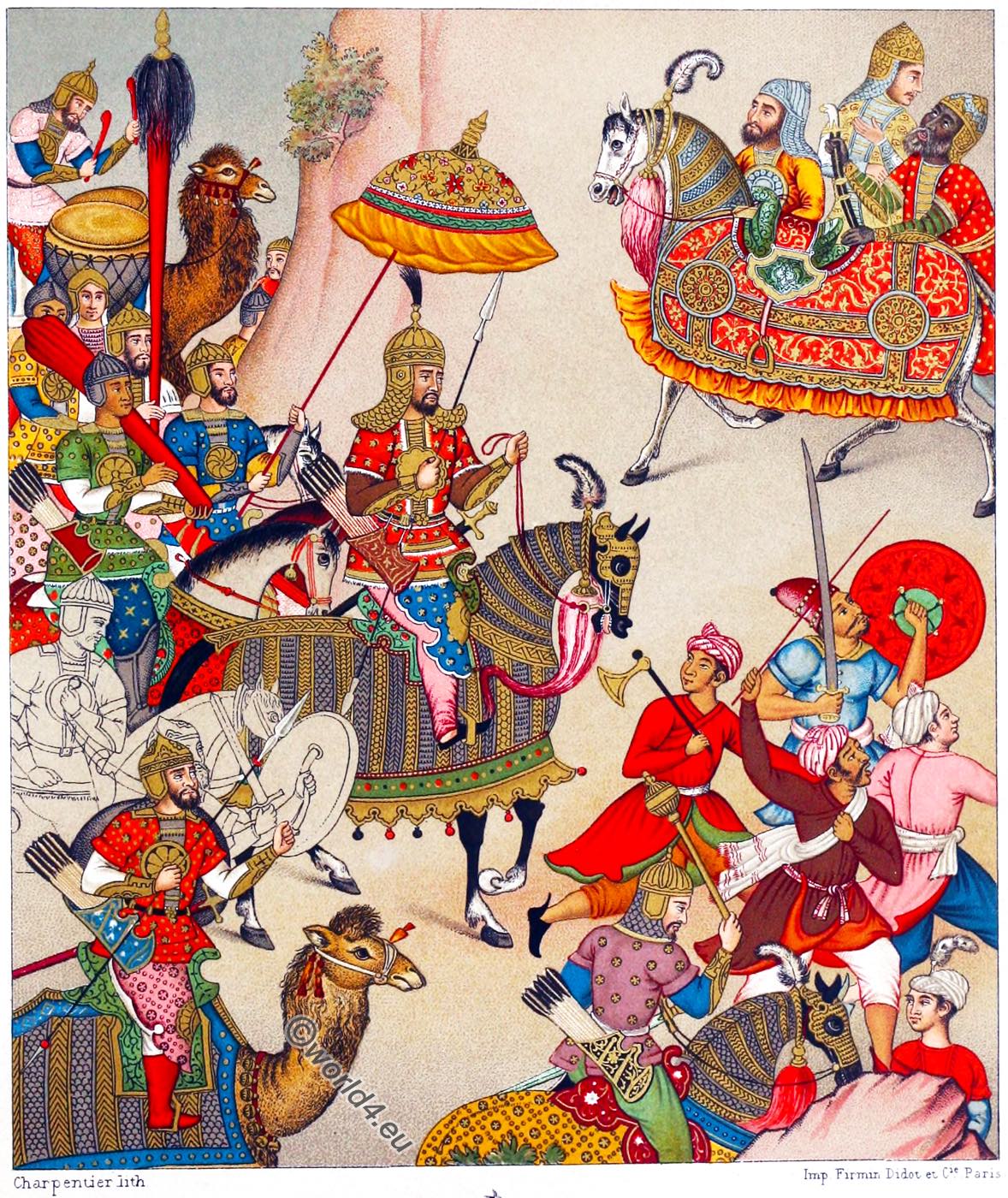

The Indian Uprising of 1857, also called the Sepoy Uprising, was directed against the colonial rule of the British East India Company over the Indian subcontinent. The uprising was mainly limited to the upper Ganga valley and central India. Centres of the uprising were Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, the north of Madhya Pradesh and the Delhi region.

The beginning of the Indian uprising of 1857 is mostly dated to 10 May 1857. On this day there was an open insurrection in Merath by Hindu and Muslim soldiers against their British commanders. The insurrection was generally triggered by the introduction of the Enfield rifle, whose paper cartridges were treated with a mixture of beef tallow and lard according to a rumour widespread among British Indian forces. Since the cartridges had to be bitten before use, their use was a violation of their religious regulations for both believing Hindus and Muslims.

The real causes are the social and economic policies pursued by the British East India Company, which caused large sections of the Indian population to lose land rights, employment opportunities and influence, the increasing efforts to Christianize India in the 19th century, and the annexation of Indian princely states through the application of the Doctrine of Lapse. There is no consensus in historiography as to which of these factors is particularly important. Historians have also weighted the causes of the uprising very differently, depending on their own cultural, religious and political standpoints.

After the suppression, the East India Company was dissolved by the Government of India Act 1858 and British India became a formal crown colony.

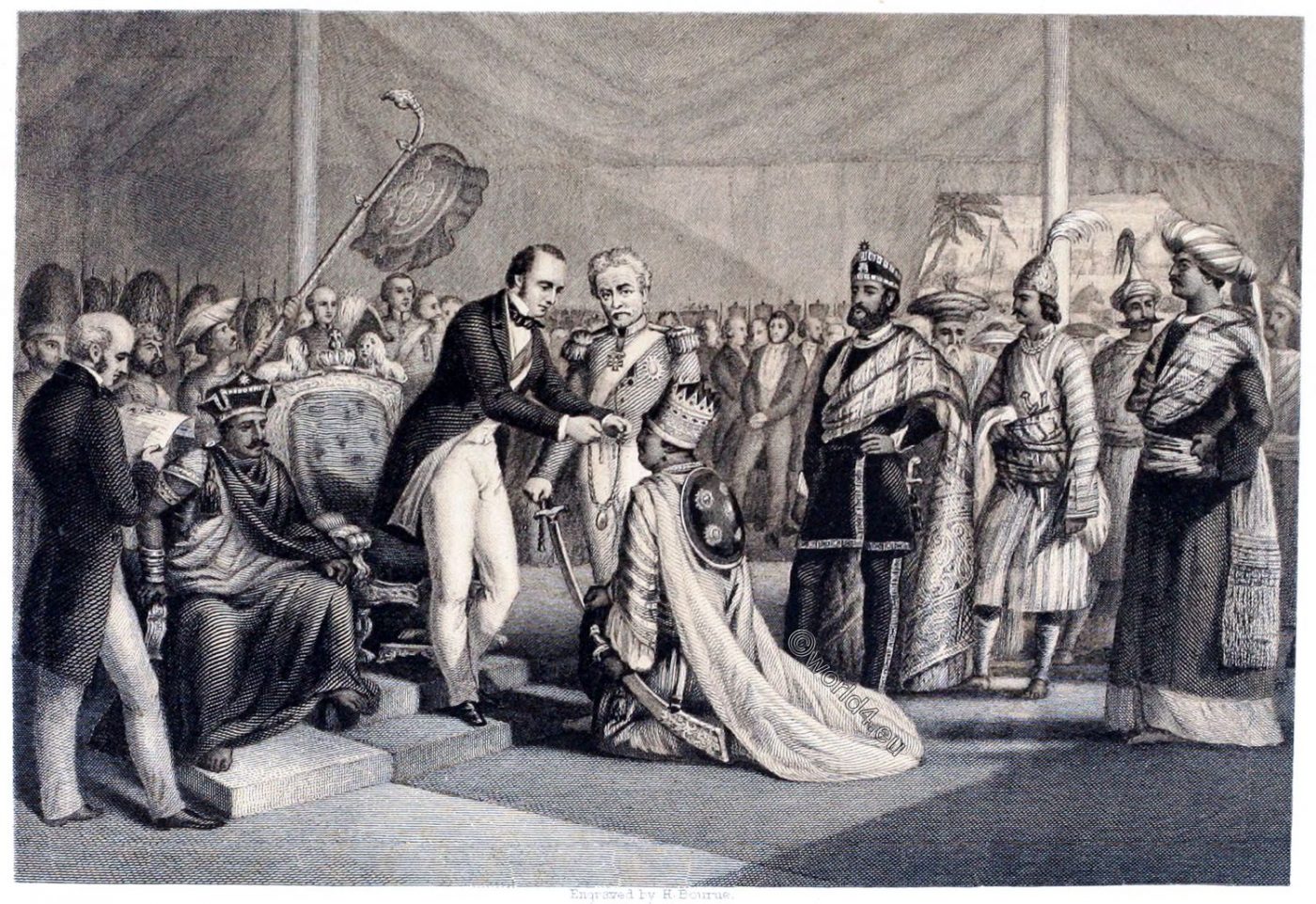

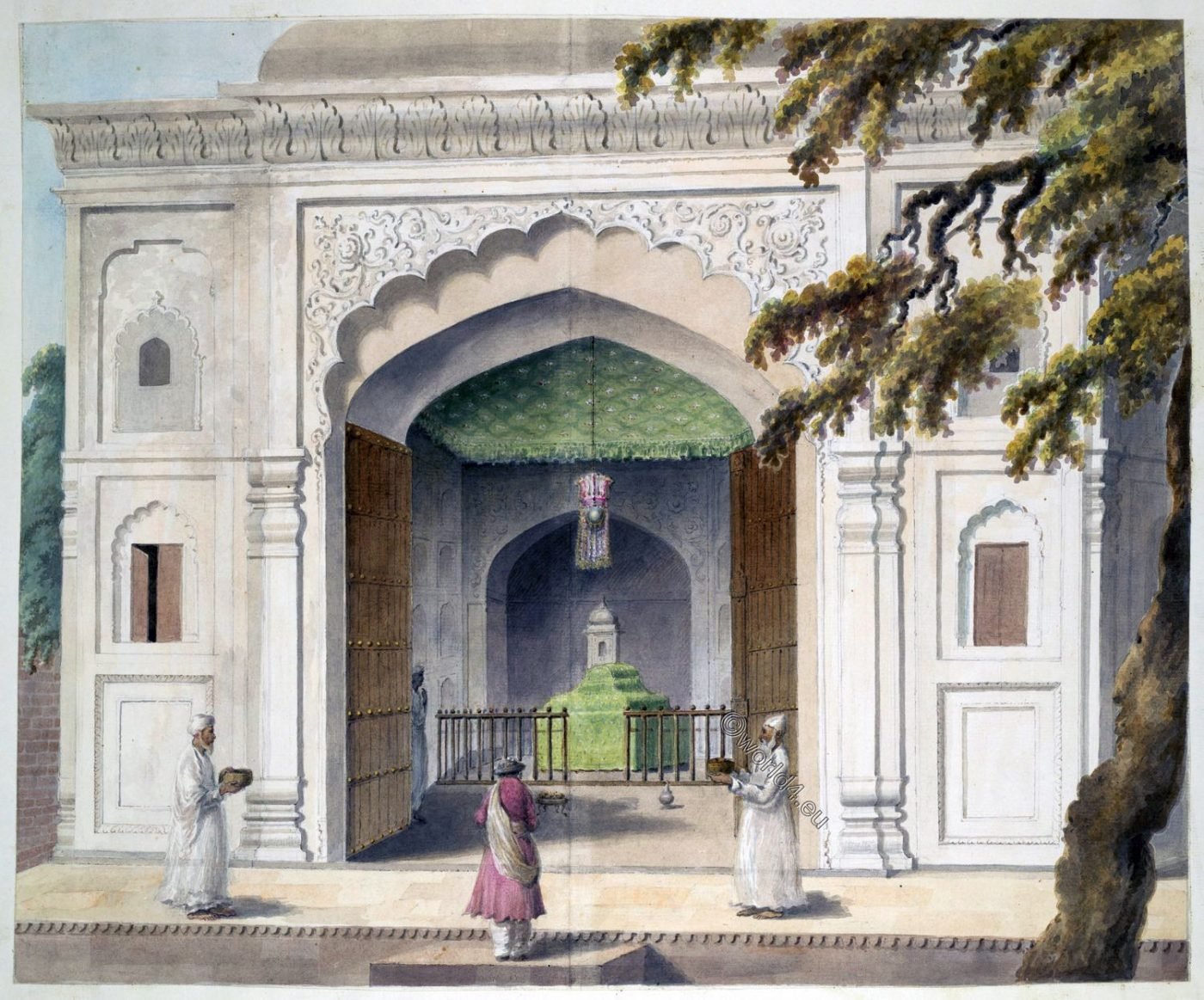

THE GRAND DURBAR AT CAWNPORE.

NOVEMBER 3, 1859.

The more recent public events which have distinguished the present period scarcely yet belong to the domain of history, and few of them have been made the subjects of historical pictures. The vast and rapid progress made by this country during the last quarter of a century baffles the effort to represent either pictorially or by brief description the successive stages of the national advance, nor has a period so crowded with important achievements found many interpreters capable of translating even its more prominent occurrences into the language of art.

One of the foremost of these, the visit of the heir to the throne to India, gave occasion for so many vivid and picturesque descriptions in the public journals that it may some day form the subject of more than one historical painting, especially as the journey made by the prince to the various dependencies had some effect in consolidating the loyalty of representative native rulers and their feudal subjects. That visit may be said to have been an endorsement of the conciliatory measures which were taken after the end of the Indian mutiny in order to confirm the allegiance of native princes and to attest the determination of the English government to rule in accordance with a clement imperial policy.

The relief of Lucknow had followed the taking of Delhi, and the great remaining difficulty was the pacification and territorial settlement of the kingdom of Oude, which was placed under the control of a chief commissioner. The harsh measures by which confiscation of the property of native land-owners was contemplated aroused considerable opposition not only on the part of the East India Company, but in parliament, and it was not till the general scheme of the future government of India was accepted that the question could be finally decided.

On the 8th of July, 1858, the India Bill passed the House of Commons, on the 23rd it passed the House of Lords, and on the 2nd of August, the last day of the session, it received the assent of the crown. By its provisions the East India Company was dissolved, and to quote the words of the bill, “all the powers in relation to government vested in or exercised by the said Company in trust for her majesty, shall cease to be vested in or exercised by the said Company, and all territories in the possession or under the government of the said Company, and all rights vested, or which, if this act had not been passed, might have been exercised by the said Company in relation to any territories, shall become vested in her majesty and be exercised in her name; and for the purposes of this act India shall mean the territories vested in her majesty as aforesaid, and all territories which may become vested in her majesty by virtue of any such rights as aforesaid.”

The mutiny was practically at an end. A strong garrison had been left in Lucknow, and the hill forts in Rohilkhand (Uttar Pradesh) to which the rebels had retired were taken and their defenders put to flight. Sir Colin Campbell had directed these movements with consummate skill, courage, and perseverance, and for his distinguished services was elevated to the peerage with the title of Lord Clyde. A general pacification was promoted by the transference of the entire government of India to the British crown, and when the royal proclamation was published by the governor-general, Lord Canning, on the 1st of November, 1858, it called forth several native addresses to the queen expressive of loyalty and attachment.

The proclamation itself was well calculated at once to impress and to conciliate the native chiefs and their followers. It announced that all engagements which had been made with the native princes by the East India Company would be scrupulously maintained and fulfilled, that no extension of territorial possession was sought, and that no aggression upon it should be tolerated or encroachment upon that of others sanctioned. It held the British government bound to the natives of our Indian territories by the same obligations of duty which bound it to the other subjects of the British Empire.

Upon the important subject of religion, in which the rebellion was said to have originated, the declaration said: “Firmly relying ourselves on the truth of Christianity, and acknowledging with gratitude the solace of religion, we disclaim alike the right and the desire to impose our conviction on any of our subjects. We declare it to be our royal will and pleasure that none be in any wise favored, none molested or disquieted, by reason of their religious faith or observances, but that all shall alike enjoy the equal and impartial protection of the law; and we do strictly charge and enjoin ail those who may be in authority under us, that they abstain from all interference with the religious belief or worship of any of our subjects, on pain of our highest displeasure.” It was added that all of whatever race or creed were to be freely and impartially admitted to such offices in her majesty’s service as they were qualified to hold.

Those who inherited lands were to be protected in all rights connected therewith subject to the equitable demands of the state, and in framing and administering the law due regard was to be paid to the ancient rights, usages, and customs of India, With regard to the late rebellion the proclamation declared :- “Our clemency will be extended to all offenders, save and except those who have been or shall be convicted of having directly taken part in the murder of British subjects. With regard to such, the demands of justice forbid the exercise of mercy.

To those who have willingly given an asylum to murderers, knowing them to be such, their lives alone can be guaranteed; but in apportioning the penalty due to such persons full consideration will be given to any circumstances under which they have been induced to throw off their allegiance; and large indulgence will be shown to those whose crimes may appear to have originated in too credulous acceptance of the false reports circulated by designing men.

To all others in arms against the government we hereby promise unconditional pardon, amnesty, and oblivion of all offense against ourselves, our crown, and dignity, on their return to their homes and peaceful pursuits.

It is our royal pleasure that these terms of grace and amnesty should be extended to all those who comply with these conditions before the first day of January next. When, by the blessing of Providence, internal tranquillity shall be restored, it is our earnest desire to stimulate the peaceful industry of India, to promote works of public utility and improvement, and to administer its government for the benefit of all our subjects therein. In their prosperity will be our strength, in their contentment our security, and in their gratitude our best reward. And may the God of all power grant to us, and to those in authority under us, strength to carry out these our wishes for the good of our people!”

The proclamation promised an amnesty to all those who returned to peaceful pursuits and to their homes before the 1st of January, 1859, but much had to be accomplished for the final pacification of Oude, where the Begum issued a counter proclamation. The rebels had made this province their place of shelter and rallying point, and such decisive measures had to be adopted as could only be justified by the necessity of the case and the dangerous attitude of the enemy. Fort after fort was taken, however, and that of Shunkerpoor, for the reduction of which the whole British force in the district had been concentrated, was at last surrendered by Bainee Madhoo, an insurgent chief, who escaped probably to the hills of Nepaul, where only a cold reception awaited the vanquished rebels. 1)

Thither Nana Sahib was driven after a ruinous defeat, to become an outcast and a hunted fugitive, and to this quarter also his brother Bala Rao betook himself, after attempting a final stand in which his troops were beaten and dispersed almost without resistance. During this time, however, the pacification of the province was being effected by the constant submission of chiefs who went to the chief commissioner at Lucknow to tender their adhesion; and though desultory hostilities continued for some time afterwards they were all successfully checked, the contest in Oude was brought to an end, and the resistance of 150,000 armed men had been subdued with a very moderate loss to the British force, and with remarkable forbearance towards the misguided rebels.

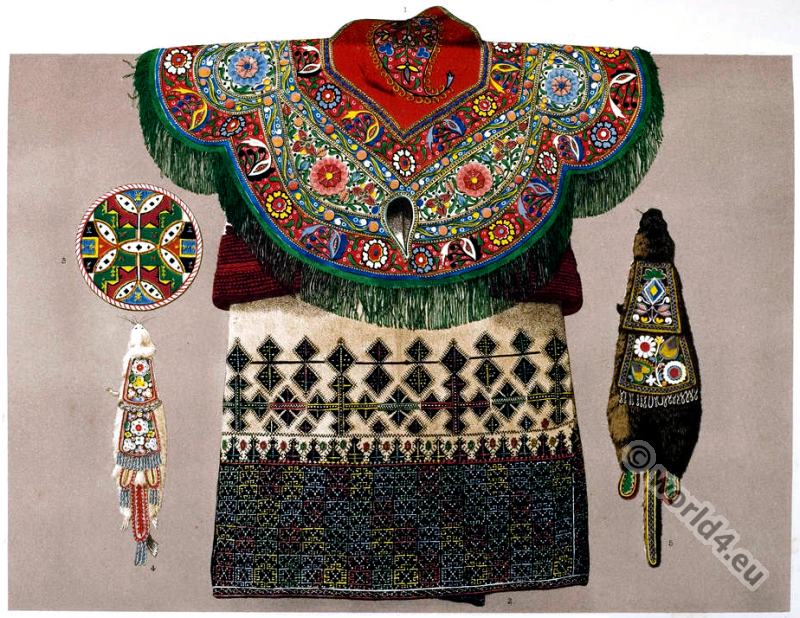

On the 12th of October, 1859, the governor-general commenced a tour through the provinces, and his journey may be said to have represented a royal progress, marked at the principal stations by the assembling of grand durbars or levees, to which the loyal chiefs were invited, and where they were received with due magnificence, that they might be presented with robes of honor, collars, chains, and various ornaments in recognition of their allegiance during the mutiny.

The most imposing of these ceremonies was the Grand Durbar which was held at Cawnpore on the 3d of November, 1859, at two o’clock in the day, in a great tent lined with yellow. In the centre of the farther side of this tent was Lord Canning’s chair, on his right was all the rajahs, on his left the chair of the commander-in-chief, and beyond that, the places reserved for Sir Richmond Shakespear, Generals Birch and Mansfield, Colonel Beecher, and Colonel Stuart. Behind them the governor-general and chief’s staff, and then a number of civilians, beyond whom were about 200 military officers.

By the appointed time all were in their seats, and the sight was a gorgeous one, because of the great variety of costumes and the brilliancy of colour. The representative rajah in point of magnificence was he of Rewah, who occupied a chair on the right hand of the viceroy. He was described at the time as a big burly man of tall stature, with a heavy grossly sensual face, and yellow complexion. His hands, fat and shapeless, were covered with dazzling rings. He wore a light yellow tunic with a black and white scarf that looked at a distance like a boa-constrictor’s skin.

On his head was a handsome towering cap composed entirely of gold and diamonds, which evidently made an inclination of the head difficult. On his right sat Mr. Cecil Beadon, the home and foreign secretary, and next him the Benares rajah, quietly dressed and with a white shawl turban. Next him again was the rajah of Chikaree, an elderly handsome man dressed in red; and besides there were above a hundred other chiefs of various degrees, not two of whom were similarly attired, so that the contrasts of colour were remarkable, and often very striking.

A passage-tent kept by the grenadier company of the 35th Regiment as a guard of honour led to the durbar tent, and soon after two o’clock the military orders, concluding with “Present arms!” announced the arrival of the viceroy, whose presence was saluted by the firing of a round of guns. He entered the durbar tent preceded by his chief secretaries of state and aides-de-camp, the assembly rising on his entrance, and remaining standing till he reached the chair of state and sat down.

Then came the presentations of the rajahs, Mr. Beadon, the home and foreign secretary, introducing the more important chiefs, and another officer the less distinguished ones, Each rajah made his most graceful obeisance, an act accompanied in every case with a nuzzur (or present), which was also in each case, after being touched by the vice-regal hand, taken from the officer by the people of the Tosha Khana department.

Then came the presentation of khelats. The principal rajahs had chains fastened on their necks, but only to one, the Rewah rajah, was this done by Lord Canning personally. To give him his chain his lordship rose and passed it round his neck. The others had their collars of honour put on by the secretaries, Lord Canning merely touching each chain when presented to him for that purpose.

The Rewah rajah, the Benares rajah, and the Chikaree rajah were each addressed by Lord Canning in English on their khelats being given them; but to the Chikaree rajah a great honour was paid, for, after saying a few words to him, Lord Canning, turning to the commander-in-chief, who on being addressed immediately stood up, the whole of the English officers present standing also, said, “Lord Clyde, I wish to bring to your notice the conduct of this brave man, who showed marked devotion to the British cause by acting on the offensive against the rebels of his own accord, and when besieged in a fort refused to give up a British officer, offering his own son as a hostage instead; and I trust,” said Lord Canning, “that every officer of the queen now present will remember this, and should they ever come in contact with this rajah, act accordingly.”

This was the crowning ceremony of the Great Durbar at Cawnpore, which may itself be regarded as the special demonstration of the British government to imply that by the pacification of the province where some of the foulest deeds of the mutiny had been committed, and where the rebellion made its last ineffectual stand, the authority of the queen had been established, and the relation between India and Great Britain had been permanently restored.

1) South Asia Archive: The Indian Empire > Chapter XXVI. Campaign in Oude;

Source:

- Pictures and royal portraits illustrative of English and Scottish history, from the introduction of Christianity to the present time : Engraved from important works by distinguished modern painters, and from authentic state portraits. With descriptive historical sketches by Thomas Archer. London: Blackie & son, 1880.

- The Queen’s Empire; or, Ind and her pearl by Joseph, jr. Moore. Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott company, 1886.