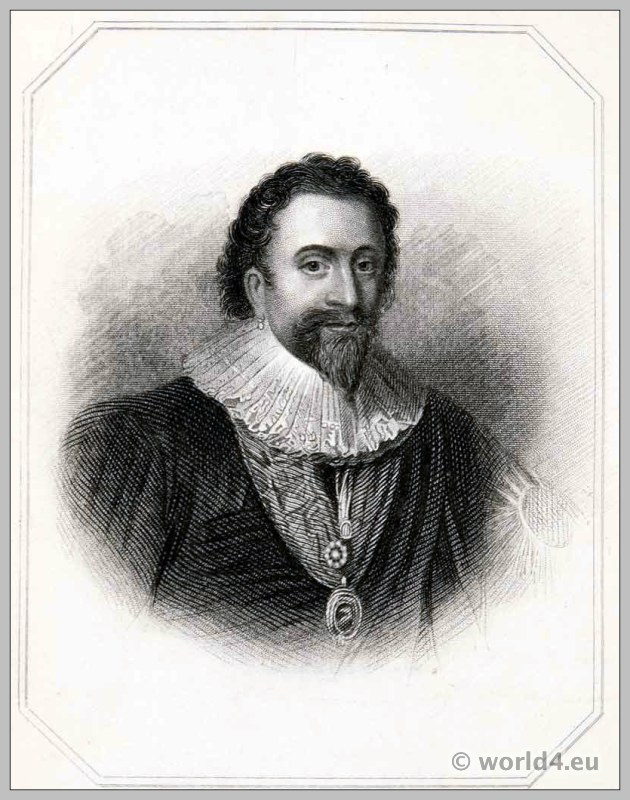

WILLIAM, THIRD EARL OF PEMBROKE.

(8 April 1580 – 10 April 1630. )

As Chancellor of Oxford University he founded Pembroke College with Jacob I. He was very interested in the colonization of America. From 1615 to 1625 he was Lord Chamberlain of the Household and from 1626 to 1630 Lord Steward. He is considered a patron of William Shakespeare.

SIR ANTHONY VAN DYCK.

87 in. H. 54 in. W. Canvas. Double Cube Room at Wilton house .

Full length, standing, turned slightly to his left; dark hair, pointed beard and mustachios; dressed in black silk with a gold embroidered sword-belt over his hip, full pendant ruff, cloak with Garter Star; a medal and jewel suspended round his neck. The left hand holds a wand and the right is extended downwards. A crimson curtain and pillar form the background.

If painted, as tradition says, from a bronze statue, which was itself executed from a design and not from the living model, this portrait is a fine example of the genius of the master; for in the painting of the head he has retained all the vigor of handling, freshness and sharpness of tone, which is almost invariably wanting in a posthumous portrait. I am not satisfied that this is the picture referred to by Gambarini, whose description runs as follows: “A moveable piece (in the great room) broader than high (done by Vandyke) viz. William Lord Stewart, whose face he (Vandyke) painted from a brass statue moulded by … from Rubens’ design, and since given by this Lord (who died a very few months since) to the University of Oxford.”

It seems improbable that Gambarini would describe this picture, which certainly occupied its present position in his time, as a movable piece, even taking the statement that it is broader than high as a printer’s error: at the same time it is only fair to point out that he would be very unlikely to omit a picture of such importance as this portrait from his catalogue.

The statue mentioned above is the work of Hubert le Sueur or Soeur, being, according to Granger, with the exception of the equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross, the only specimen of his art which now exists in England. The Rev. L. R. Phelps, of Oxford, gives the following account of its presentation to the University: “I find no trace of any signature by le Sueur on the monument to the Earl of Pembroke now in the Bodleian. It is assigned to him by Gutch, a very respectable antiquary, who was registrar of the University at the end of the 18th Century. The tradition as to the statue is curious, viz., ‘That a deputation from the University visited Lord Pembroke, then Chancellor, at Wilton. Then after dinner (honi soit qui mal y pense) their host offered to give them the statue. That the learned doctors next morning, fearing a change of mind on the part of the Chancellor, unscrewed the head and carried it off with them. The trunk followed very reluctantly.’ Such is the gossip of the day.”

The inscription below is as follows: “Hanc Patrui sui magni effigiem ad formam quam finxit Petrus Paulus Rubens aere fuso expressam D. D. Thomas Pembrochiae et Montgomeriae Comes, Honorum et virtutum Haeres. A.D. MDCCXXIII. Gulielmus Pembrochiae Comes Regnantibus Jacobo et Carolo I Hospitii Regni Camerarius et Seneschallus, Academiae Oxoniensis Cancellarius Munificentissimus.”

It is remarkable that the arms on the pedestal are those of Philip, fourth Earl of Pembroke.

In Hearne’s Diaries (§ 96, p. 1 I) is the following amusing note on the letter of thanks from the University authorities:

“April 19th Friday 1723.- 0n Wednesday last at two o’clock in the afternoon was a convocation in which a letter was read to give thanks to the present Earl of Pembroke for a fine brass statue his Lordship hath presented to the University representing one of his ancestors, viz, that Earl of Pembroke that gave the University the Baroccian collection of Greek MSS. I am told that this letter is very silly and poor and that among other things his Lordship is told in it that the statue is placed in ‘aede immortalitatis.’ Now what this ‘aedes immortalitatis,’ Church, Temple, or Chappel of immortality is I cannot conceive, but am sure that ye statue is at present fix’d in the Picture Gallery, adjoyning to the Bodleian Library.”

William, third Earl of Pembroke, eldest son of Henry, 1) second Earl, by his third wife, the famous Mary Sidney, 2) was born at Wilton on the 8th April, 1580; 3) he became a nobleman of New College, Oxford, in Lent term, 1592, aged thirteen, and continued there about two years. 4) He was made a Knight of the Garter in 1603, 5) having succeeded to the family honors two years previously. Sir Dudley Carleton mentions this investiture as taking place at Windsor on the Sunday before the 28th June, the other recipients of the honor being the Duke of Lennox, and the Earls of Mar and Southampton. 6)

In 1608 the Earl gained much honor in a quarrel with Sir George Wharton, son of Philip, Lord Wharton: “On Friday was seven night my Lo, and Sir George, with others, played at cards, where Sir George showed such choler that my Lo. of Pembroke tould him. Sir George, I have loved you long, and desire still to do so; but by your manner in playing, you lay it on me either to leave to love you, or to leave to play with you, wherefore, choosing to love you still, I will never play with you more.” 7)

In 1607 he was made Governor of Portsmouth, 8) and on the 20rd December, 1615, “the King returned to Westminster and delivering the Staff to the Earl of Pembroke, appoints him to be Chamberlain.” (Camden.)

1) There is no portrait of Henry, second Earl of Pembroke, at Wilton; an account of his life is given in Appendix III.

2) See GEERARTS.

3) On the south entrance of the old church at Wilton was the following tablet: “Be it remembered that at the eighth day of April 1589 (sic) before 12 of the clock at night of the same day, was born William Lord Herbert of Cardiffe, first child of the noble Henry Herbert Erle of Pembroke, by his most dere wyfe Mary, daughter to the Right Hon. Henry Sidney, Knight of the most noble order etc: and the Lady Mary, daughter to the famous John Duke of Northumberland, and was Xt’ned the 28th day of the same Month in the manor of Wilton. The God-mother, ye mighty and most excellent Princesse Elizabethe by the Grace of God Queene of England, by her deputye the most virtuous Lady Anne Countice of Warwick; and the God-fathers were the noble and famous Erie Ambrose Erle of Warwick, and Robert Erle of Lycester, both great-uncles to the infant by the mother’s side, Warwick in person and Lycester by his deputy Philip Sydney Esq, uncle by the mothers side to the forenamed Lord Herbert of Cardiff, whom the Almighty and most gracious Lord blesse, with his mother above named, with prosperous life in all happiness, in the name of God. Amen.”

4) Wood, Athenae Oxonienses, vol. i, p. 546.

5) Annal. R. Jac. per Camden.

6) Nichols’ Progresses of K. James I, p. 190. Sir Dudley Carleton to Sir Thomas Parry.

7) Ibid, vol. ii, p. 430.

8 Pat. 7, Jac., p. 38.

At the funeral of Queen Anne four years later he was one of the Pall-bearers, his brother, then Earl of Montgomery, bearing the Great Banner with the Earl of Tullibardine.1)

In 1626 he was unanimously elected Chancellor of the University of Oxford,2) and about that time was made Lord Steward of the King’s Household, and to these dignities he added those of Warden, and Chief Justice of all the forests south of Trent, and Warden of the Stannaries. 3)

The Earl married 4) in 1604 Mary, eldest daughter of Gilbert Talbot, seventh Earl of Shrewsbury, and by her had two sons, James, born in 1616, and Henry, born in 1621, both of whom died in infancy.

A curious account is given of his death, which took place at Baynards Castle 5) on the 20th April, 1630: “A short story,” says Clarendon, “may not be unfitly inserted, it being very freely mentioned by a Person of known integrity, whose Character is here undertaken to be set down, and who, at that time being on his way to London, met at Maidenhead some persons of quality, of relation or dependence upon the Earl of Pembroke, (Sr Charles Morgan commonly called General Morgan, who had commanded an army in Germany and defended Stoad; Dr Field then Bishop of St Davids; and Dr. Chafin the Earls then Chaplain in his house, and much in his favor): at supper one of them drank a health to the Lord Steward: upon which another of them said, ‘That he believed his Lord was at that time very merry, for he had now outlived the day, which his tutor Sandford had prognosticated upon his Nativity that he would not outlive; but he had done it now, for that was his birthday which had completed his age to fifty years;’ the next morning by the time they came to Colebrook they met with the news of his death.”

1) Camden’s MS. (Harl. MSS., 5176). A drawing by Sir William Camden of the funeral procession of Queen Elizabeth in the year 1603 exists in the British Museum showing “The Great Embrothered Banner of England borne by Ye Erle of Pembroke, assisted by ye L. Howard of Effingham.”

2) Wood, Athenae Oxonienses, vol. i, p. 546. Pembroke College, originally Broadgates Hall, was refounded (by Thomas Tesdale and Richard Wightwich) in 1624 [sic] during the time of his Chancellorship, and received its name from him, but nothing else save a piece of plate now (1894) no longer in existence.-Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. vi, p. 219.

3) Collins.

4) Rowland Whyte, in a letter to Sir Robert Sydney, dated the 5th of December, 1595, writes: “Sir George Carey takes it very unkindly that my Lord of Pembroke broke off the match intended between my Lord Herbert and his daughter, and told the Queen it was because he would not assure him 1000l. a Yeare which comes to his daughter as next a Kinne to Queen Anne Bullen.”-Sydney Papers, vol. i, p.372.

5) Kennet states that he supped with the Countess of Bedford at Bishops Gate on his birthday, 10th April, 1630, and died the same night of an apoplexy, aged 70; he is obviously in error as regards the Earl’s age.

Among the Ashmole MSS. is a note to the effect that” William Earle of Pembroke, who dyed 10 Ap. 1630, had his nativity calculated by Mr Sandford his tutor, who judged that he should not live beyond such a day, and yt night he dyed of an Apoplex.” 1) Wood in his Athenae gives the credit of the prediction to a Mr. Tho. Allen of Gloc [?GloucesterJ Hall. Granger adds the following strange note to his account of the Earl’s death: “When his body was opened, in order to be embalmed, he was observed, immediately after the incision was made, to lift up his hand. This remarkable circumstance, compared with lord Clarendon’s account of his sudden death, affords a strong presumptive proof that his distemper was an apoplexy. This anecdote may be depended on as a fact, as it was told by a descendant of the Pembroke family, who had often heard it related.”

Commanded as a youth to the Court, where his father was in high favor, Lord Herbert seems to have disappointed his friends by not taking advantage of his position to improve his fortunes. “Now that my Lord Harbert is gone,” writes Rowland Whyte, “he is much blamed for his cold and weake Maner of pursuing Her Majesties Favor, having had soe good Steps to leade him unto it. There is a want of Spirit and Courage laid to his Charge, and that he is a melancholy young man.” This lack of enterprise was due partly, no doubt, to the fact that his father was about this time seriously ill, his temporary absence from the Court being due to this cause; but it was this same negligence to promote his own fortunes to the detriment of others that earned him the admiration and respect of his countrymen. A year later, in 1600, he roused himself from his melancholy. “My Lord Harbert,” says Whyte in a letter to Sir Robert Sidney, “resolves to show himself a man of arms, and prepares for it; and because yt is his first time of running, yt were good he came in with some excellent devise,” and in the following letter, “my Lord Harbert is practising at Greenwich: he leapes, he daunces, he sings, he gives counterbuffes, he makes his horse move with more speede,” etc.

Strangely differing in character from his brother Philip, the Earl earned a magnificent tribute from Lord Clarendon.

“The Earl of Pembroke,” he writes, “was a man of another mould and making, and of another fame and reputation with all men, than Lord Arundel, being the most universally beloved and esteemed of any man of that age; and having a great office in the court, he made the court itself better esteemed, and more reverenced in the country. And, as he had a great number of friends of the best men, so no man had ever the confidence to avow himself to be his enemy. He was a man very well bred, and of excellent parts, and a graceful speaker upon any subject, having a good proportion of learning, and a ready wit to apply to it and enlarge upon it; of a pleasant facetious humour, and a disposition affable, generous, and magnificent.

1) MSS. Ashmole, 174, fol. 149.

He was master of a great fortune from his ancestors, and had a great addition by his wife, heir of the Earl of Shrewsbury, which he enjoyed during his life, she out-living him: but all served not his expense, which was only limited by his great mind and occasions to use it nobly.

“He lived many years about the court, before in it, and never by it; being rather regarded and esteemed by King James, than loved and favored. After the foul fall of the Earl of Somerset, he was made lord chamberlain of the King’s house, more for the court’s sake than his own; and the court appeared with more lustre because he had the government of that province. As he spent and lived upon his own fortune, so he stood upon his own feet, without any other support than of his own proper virtue and merit: and lived towards the favorites with that decency, as would not suffer them to censure or reproach his master’s judgment, and election, but as with men of his own rank. He was exceedingly beloved at court, because he never desired to get that for himself which others labored for, but was still ready to promote the pretenses of worthy men. And he was equally celebrated in the country, for having received no obligation from the court, which might corrupt or sway his affections or judgment: so, that all who were displeased or unsatisfied in the court, were always inclined to put themselves under his banner, if he would have admitted them; and yet he did not so reject them, as to make them choose another shelter, but so far suffered them to depend on him, that he could restrain them from breaking out beyond private resentments and murmurs.

“He was a great lover of his country, and of the religion and justice, which he believed could only support it; and his friendships were only with men of those principles. And as his conversation was most with men of the most pregnant parts and understanding, so towards any such, who needed support or encouragement, though unknown, if fairly recommended to him, he was very liberal. Sure never man was planted in a court, that was fitter for that soil, or brought better qualities with him to purify the air.

“Yet his memory must not be flattered, that his virtues, and good inclinations may be believed; he was not without some alloy of vice, and without being clouded with great infirmities, which he had in too exorbitant proportion. He indulged to himself the pleasures of all kinds, almost in all excesses. To women, whether out of his natural constitution, or for want of his domestic content and delight (in which he was most unhappy, for he paid much too dear for his wife’s fortune, by taking her person into the bargain), he was immoderately given up. But therein he likewise retained such a power and jurisdiction over his very appetite, that he was not so much transported with beauty, and outward allurements, as with those advantages of the mind, as manifested an extraordinary wit, and spirit and knowledge; and administered great pleasure in the conversation. To these he sacrificed himself, his precious time, and much of his fortune. And some, who were nearest his trust and friendship, were not without apprehension, that his natural vivacity and vigour of mind began to lessen and decline by those excessive indulgences.

“He died exceedingly lamented by men of all qualities, and left many of his servants and dependants owners of good estates, raised out of their employments and bounty. Nor had his heir cause to complain. For, though his expenses had been very magnificent (and, it may be, less considered, and his providence the less, because he had no child to inherit), so much as he left a great charge on the estate; yet, considering the wealth he left in jewels, plate and furniture; and the estate his brother enjoyed in the right of his wife (who was not fit to manage it herself), during her long life, may justly be said to have inherited as good an estate from him, as he had from his father, which was one of the best in England.”!

Wood’s estimate of his character and person is equally interesting: “The Earl of Pembroke,” he writes, “was not only a great favorer of learned and ingenious men, but was himself learned, and endowed to admiration with a poetical geny, as by those amorous and poetical aires and poems doth evidently appear; . . . he was the very picture and viva effigies of nobility. His person was rather majestic than elegant, and his presence, whether quiet or in motion, was full of stately gravity. His mind was purely heroic, often stout, and never disloyal; and so vehement an opponent of the Spaniard, that when that match fell under consideration in the latter end of the reign of James I, he would sometimes rouse to the trepidation of that King, yet kept in favour still; for his Majesty knew plain dealing (as a jewel in all men so) was in a privy counsellor an ornamental duty; and the same true heartedness commended him to Charles I.” 2)

Ben Jonson’s Epigram on the Earl runs as follows:

I do but name thee, Pembroke, and I find

It is an epigram on all mankind;

Against the bad, but of, and to the good:

Both which are ask’d to have thee understood.

Nor could the age have miss’d thee, in this strife

Of vice and virtue, wherein all great life

Almost is exercised; and scarce one knows,

To which, yet, of the sides himself he owes.

They follow virtue for reward to-day;

To-morrow vice, if she give better pay:

And are so good, and bad, just at a price,

As nothing else discerns the virtue or vice.

But thou, whose noblesse keeps one stature still,

And one true posture, though besieged with ill

Of what ambition, faction, pride can raise;

Whose life, even they that envy it must praise;

That art so reverenced, as thy coming in,

But in the view, doth interrupt their sin;

Thou must draw more: and they that hope to see

The commonwealth still safe, must study thee. 3)

1) Clarendon, vol. i, p. 56.

2) Athenae Oxonienses, vol, i, p. 546.

3) Epigrams, Lib. i, ep. 102.

Some of the amatory poems ascribed to the Earl of Pembroke are neat, lively, and polished. They were addressed, it seems, to Christiana, daughter of Lord Bruce of Kinloss, one of the favorites of James I, who, to facilitate her match with William, Lord Cavendish, gave her a fortune of £ 1O,OOO. 1) This lady in her youth was the platonic mistress of Lord Pembroke, 2) who, according to the romantic gallantry of his age, composed many poems in her praise. These her ladyship seems to have carefully treasured and committed to the editorial care of the son of Dr. Donne (John Donne inscribes the volume “to the right honorable Christiana Countess of Devonshire, dowager”), who with Waller and Denham probably formed part of the bevy of wits that assembled at the Countess’s literary coterie. 3) These poems were published with this title:

“Poems written by the Right Honorable William Earl of Pembroke, Lord Steward of his Majesties Household whereof many of which are answered by way of Repartee by Sr Benjamin Ruddier 4) Knight with several distinct Poems written by them Occasionally and Apart. London Printed by Matthew Inman, and are to be sold by James Magnes, in Russel-street, near the Piazza, in Covent-Garden, 1660.”

The following verses are a good example of his style:

A PASTORAL.

LOVER P(EMBROKE).

Shepherd, gentle Shepherd hark,

As one that canst call rightest,

Birds by their Name,

Both wild and tame,

And in their Notes delightest:

What Voice is this, I prithee mark,

With so much Musick in it?

Too sweet methinks to be a Lark,

Too loud to be a Linnet.

Nightingales are more confus’d,

And discant more at random,

Whose warbling throats,

(To hold out Notes)

Their airy tunes abandon.

Angels stoop not now adaies,

Such Quirresters forsake us;

Yet Syrens may

Our Loves betray,

And wretched Pris’ners make us;

Yet they must use some other way,

Than singing to deprive us

Of our poor lives, since such sweet lays

As these would soon revive us.

SHEPHERD R(UDYARD).

‘Tis not Syren we discry,

Nor Bird in Grove residing,

Nor Angels Voice,

Although as choice,

Fond Boy thou hearst dividing;

But one if either thou or I

Should face to face resemble her,

To any of these would blushing cry,

Away, away Dissembler.

1) Collins, vol. i, p. 300.

2) Notes on the portraits at Woburn Abbey by H. W., 1791.

3) Walpole, Royal and Noble Authors, ed. 1806, vol. ii, p. 254.

4) Generally spelt Rudyard.

Thomas Park, in his notes on Walpole’s Royal and Noble Authors, gives two examples of the Earl’s poetry: “the first, as seeming to claim a place in Dr. Aiken’s selection of ingenious and witty songs; the second as vying with the elegant conceits of Waller or Carew.” The so-called Sonnet, however, is generally accepted as the work of Sir Walter Raleigh.

SONNET.

Wrong not, dear Empress of my heart,

The merits of true passion,

With thinking that he feels no smart

Who sues for no compassion.

Since, if my plaints seem not to prove

The Conquest of thy Beauty;

It comes not from defect of Love,

But from excess of duty.

For knowing that I sue to serve

A Saint of such perfection,

As all Divine, but none deserve

A place in her affection;

I rather chuse to want relief

Than venture the revealing:-

Where glory recommends the grief,

Despair destroyes the healing.

Thus those desires that climb too high

For any mortal Lover,

When Reason cannot make them dye

Discretion doth them cover:

Yet when Discretion both bereave

The plaints which I should utter

Then thy Discretion may perceive

That silence is the suitor.

Silence, in Love, betrays more wo

Than words, though ne’er so witty;

The beggar that is dumb, you know,

May challenge double pitty.

Then wrong not, dear heart of my heart,

My true though secret passion;

He smarteth most that hides his smart

And sues for no compassion.

TO A LADY WEEPING.

Dry those fair, those Christal Eyes,

Which like growing Fountains rise

To drown their Banks; Grief’s sullen Brooks

Would better flow from furrow’d looks:

Thy lovely Face was never meant

To be the Seat of Discontent.

Then clear those wat’rish stars again,

That else portend a lasting Rain,

Lest the Clouds which settle there

Prolong my Winter all the year;

And thy Example others make

In Love with sorrow for thy sake.

“The Epistle Dedicatori” of the first folio edition of Shakespeare’s Plays (1623), by John Heminge and William Condell begins thus:

“To the most noble

and

incomparable paire

of brethren

WILLIAM

Earle of Pembroke &c Lord Chamberlaine to the

King’s most Excellent Maiesty

and

PHILIP

Earle of Montgomery, &c, Gentleman of his Maiesties

Bed-Chamber. Both Knights of the most Noble Order

of the Garter and our singular good

Lords.”

So much has been written for and against the theory that the Mr. W. H. to whom Shakespeare’s Sonnets were dedicated was William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, that I shall not venture into the troubled waters of that controversy. Mr. Thomas Tyler in his introduction to the Sonnets (London, 1890), propounds a very fair case in favour of the Herbert proposition.

Shakespeare’s comedy of Twelfth Night is said to have been first acted before James I at Wilton in 1603, the author being present at the representation. In 1593 the Earl of Pembroke sheltered under his protection a company of players, who made a profession of acting as a mode of livelihood, and who were more desirous of profit than emulous of praise. This company began to play at the Rose on the 28th October, 1600. 1) It is possible that the play was presented by this company.

Shortly after succeeding to the earldom, Lord Pembroke fell into disfavor on account of a liaison with Mary Fitton, one of the Queen’s ladies. Sir Robert Cecil in a letter to Sir George Carew, dated 5th February, 1601, writes: “We have no news, but there is a misfortune befallen Mistress Fitton, for she is proved with child, and the Earl of Pembroke being examined confesseth a fact, but utterly renounceth all marriage. I fear they will both dwell in the Tower awhile, for the queen hath vowed to send them thither.” 2) Again, Tobie Mathew in a note to Dudley Carleton, dated 25th March, 1601, writes: “The Earl of Pembroke is committed to the Fleet: his cause is delivered of a boy who is dead.” For this misdemeanor the Queen also revoked the gift of the office of Constable of St. Briavels, in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire; Sir Edward Winter received the appointment, but surrendered it on 10th January, 1608, when it was regranted to Lord Pembroke, then reinstated in the royal favour. 3)

1) From An apology for believers of the Shakespeare Papers, 1797, Anon.

2) Calender of Carew MSS.

3) Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1603-1610.

FLEMISH SCHOOL (SEVENTEENTH CENTURY). WILTON HOUSE PICTURES.

WILLIAM, THIRD EARL OF PEMBROKE(?).

Flemish School.

16 in. H. 13 in. W. Panel. Single Cube Room.

Head and shoulders turned to his left, wearing a black doublet slashed with yellow, a broad falling ruff, and a broad blue riband with pendant jewel round his neck. The background is dark and upon it is the following inscription: “William Earl of Pembroke ob 1630.”

On the back of the panel is a parchment on which are the following lines from Shakespeare’s eighty-first Sonnet:

Your monument shall be my gentle verse,

Which eyes not yet created shall o’er-read;

And tongues to be, your being shall rehearse,

When all the breathers of this world are dead;

You still shall live—such virtue hath my pen—

Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men.

Below this are the lines:

William Earl Pembroke died suddenly April 10th 1630. When his body was opened in order to be embalmed he was observed, on the incision being made, to lift up his hand. This circumstance may be depended on as a fact, having been related by a member of the family, and was considered by the faculty to afford strong presumptive evidence that the distemper of which he died was apoplexy.

This account, taken directly from Granger’s Biographical History 1) shows that the parchment was not added before 1769, when that work was published. The presence of the Sonnet has been claimed as evidence that William, Earl of Pembroke, was the H. W. of Shakespeare; the style of the writing, however, is that of the latter end of the eighteenth century, if not later, and I think it probable that the parchment is forged and affixed to a Flemish portrait of the school of Gonsales Coques, which probably did not originally represent the Earl, and a reproduction is given of the picture in the hope that it will lead to the identification of the original portrait.

An account of William, third Earl of Pembroke, is given under Vandyck.

1) The exact wording of Granger’s account is as follows: “When his body was opened, in order to be embalmed, he was observed, immediately after the incision was made, to lift up his hand. This remarkable circumstance, compared with Lord Clarendon’s account of his sudden death, affords a strong presumptive proof that his distemper was an apoplexy. This anecdote may be depended on as a fact, as it was told by a descendant of the Pembroke family, who had often heard it related.”—History of England (ed. 1804), vol. i, p. 330.

Source: Wilton house pictures; containing a full and complete catalogue and description of the three hundred and twenty paintings which are now in the possession of the Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery at his house at Wilton, in the county of Wiltshire: illustrated by seventy-two reproductions in photogravure of the most celebrated pieces by Sidney Herbert Earl of Pembroke. London, Printed at the Chiswick press, 1907.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.