CHAPTER X

THE PERFUMERS ART IN ITALY AND IN FRANCE

THE art of perfumery began to be cultivated in Italy early in the sixteenth century, when Venice became the centre for the trade in aromatic gums and sweet-smelling woods, brought to that city from Constantinople and the East by the ships of the merchants.

A demand arose from the princes and nobles, who at this time began to use perfumes largely in their palaces in the city of the Doges.

The monks, who had long cultivated flowers and plants in the monastic gardens and knew something of botany and chemistry, appear to have been the first to supply the demand.

The fashion soon spread south to Florence, for as early as 1508 a laboratory for the manufacture of perfumes was founded in the monastery of Santa Maria Novella in that city. It was established by the Dominicans, who, like most of the monastic orders, were skilled in the medicinal use of herbs.

Each director is said to have set himself out to devise some new recipe to add to the fame of the order, and so the preparations made in the monastery became celebrated, not only throughout Italy, but also in other countries.

Fra Angiolo Paladini originated sevei al applications for the skin and devised an almond paste, a lily-water, and a cosmetic vinegar which achieved renown among the ladies of the Tuscan Court. Fra Cavalieri invented a Cinchona Elixir in 1659 which was highly valued for fevers. Another director, Fra Ludivico Berlingacci, in 1707? discovered and made his famous “Life Elixir”; and Pope Innocent XI presented the Order with a wonderful recipe for burns which became known as “Balsam Innocenziano.” *)

*) This balm was mainly used for healing wounds previously cleaned by means of cooked leaves of fig, horehound and clover as well for healing bruises and sciatica. It was also an excellent medicament for spleen and stomachache.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the laboratory became well known for its scents, which were placed in tiny bottles in small boxes or cases, often in the shape of a book, the cover being stamped with ornamental devices in gold or colour.

In one of the recently published “Pepys letters,” from his nephew John Jackson, who was making the grand tour in Italy, there is an allusion to one of these little cases in the form of a book. Among the articles he sent his uncle from Leghorn he mentions “one small book of Florence essences,” which there is little doubt was one of the products of the Santa Maria Novella laboratory. He also alludes to “a franchepan ball,” probably a preparation of the famous Frangipani perfume that was then so much used in Rome, and a “small paper of pastilles to burn for fumigation,” which were at that time evidently a curiosity.

The story of the origin of the perfume known as Frangipani is an interesting one. The formula is said to have been first devised by a Roman nobleman, a member of the Frangipani family, whose name is said to have been derived from an office performed by its members, who had the right to supply the wafer or bread to the Church for sacramental purposes.

Originally the perfume was in the form of a dry powder and was used in little bags or in a soft mass for the cassolette. The liquid scent is said to have been first made by Mercutio Frangipani, a grandson of the inventor, who found that by digesting the dry ingredients in spirit of wine he obtained a more lasting perfume. It is stated that he was a learned student of botany and accompanied Columbus on his voyage to the West Indies.

It was he who told his fellow-voyagers that the perfume which was wafted to them on approaching the Island of Antigua came from the flowers, which they found in great quantities. The Plumiera alba, which has a very powerful odour, was among them, and the inhabitants of the island still call it the Frangipani flower.

Another member of the family served in the Papal Army in France in the reign of Charles IX, and to his grandson, the Marquis Frangipani, is attributed a process for perfuming gloves, known as Frangipani gloves, which became fashionable at that time.

In connexion with Italy, mention should be made of the “Golden Rose,” the special gift of the Popes to royal personages or distinguished women, as the highest mark of their esteem. It is said to have originally taken the form of the model of a single flower in gold, but in more recent times it has been made in the shape of a small tree with several flowers, mounted on a golden stand. It is sometimes richly ornamented and studded with precious stones, and the flowers are perfumed with ambergris, musk, and other aromatics.

Before the fifteenth century it was simply anointed with balsam and perfumed with musk, the thorns and the petals being tinged red to symbolise the Passion, but latterly, the “Golden Rose” has been blessed by the Pope each year with a certain ritual. After this he takes it in his left hand and blesses the people, and this is followed by the celebration of Mass in the Sistine Chapel.

King Henry VIII received the “Golden Rose” from Pope Clement; in 1861 it was awarded to the Queen of Spain; and in 1862 it was given to the Empress of the French.

France has been associated with the cultivation of sweet-smelling flowers from early times, and there is a tradition that the Romans imported and obtained many of their perfumes from ancient Gaul. It was customary with them to place perfume boxes with the dead, but it was not until the time of Francis I and Catharine de’ Medici that perfumery may be said to have become an art.

As early as 1190 there is record that there were makers and sellers of perfumes in Paris, and under Colbert the perfumers obtained patents registered in Parliament, and their fraternity was established at St. Anne’s Chapel in the Church of the Innocents.

By patents granted by King Henry VI of England and France in 1426 the arms of the perfumers were registered in the Armorial General of France. They are interesting as showing their connexion with the art of perfuming gloves, and are represented by three red gloves and a gold perfume box or cassolette.

Catharine de’ Medici brought among her entourage from Italy, Cosmo Ruggiero, her astrologer and alchemist, who is said to have made her essences, perfumes, and powders. He had an apartment allotted to him in the Tuileries which was connected with those of the Queen by a secret staircase. She also had in her train a Florentine named René (René the Florentine, commonly known as Maître Rene), who was expert in the art of making perfumes. He opened a shop in Paris which soon became the meeting-place of the fashionable world of the period. His scents and cosmetics speedily became famous and were used by all the beauties of the Court.

Dumas gives an interesting and picturesque description of the shop of René at the close of the sixteenth century. He says: “In the midst of the houses which bordered the line of the Pont-Saint-Michel, facing a small islet, was a house remarkable for its panels of wood, over which a large roof impended. The low facade was painted blue with rich gold mouldings, and a kind of frieze, which separated the ground from the first floor, represented groups of devils in the most grotesque postures imaginable. It was in the shop on the ground-floor that there was the daily sale of perfumery, unguents, cosmetics, and all the articles of a skilful chemist.

“In the shop, which was large and deep, there were two doors, each leading to a staircase. Both led to a room on the first floor, which was divided by tapestry suspended in the centre, in the back portion of which was a door leading to a secret staircase. Another door opened to a small chamber, lighted from the roof, which contained a large stove, alembics, retorts, and crucibles; it was an alchemist’s laboratory.

“In the front portion of the room on the first floor were Ibises of Egypt; mummies with gilded bands; the crocodile yawning from the ceiling; death’s heads with eyeless sockets and gum less teeth, and here old musty volumes, torn and rateaten, were presented to the eye of the visitor in pell-mell confusion. Behind the curtain were phials, singularly-shaped boxes and vases of curious construction; all lighted up by two silver lamps which, supplied with perfumed oil, cast their yellow flame around the sombre vault, to which each was suspended by three blackened chains.”

A romantic story is related of the tragic end of the beautiful Gabrielle d’Estrées when she was sent by Henry IV from Fontainebleau to Paris.

He had arranged for her to go to the house of Zametti, an Italian Jew, who had originally come to France in the household of Catharine de ’Medici and had become chief money-lender to the King. He lived in great style in a magnificently furnished palace near the Arsenal.

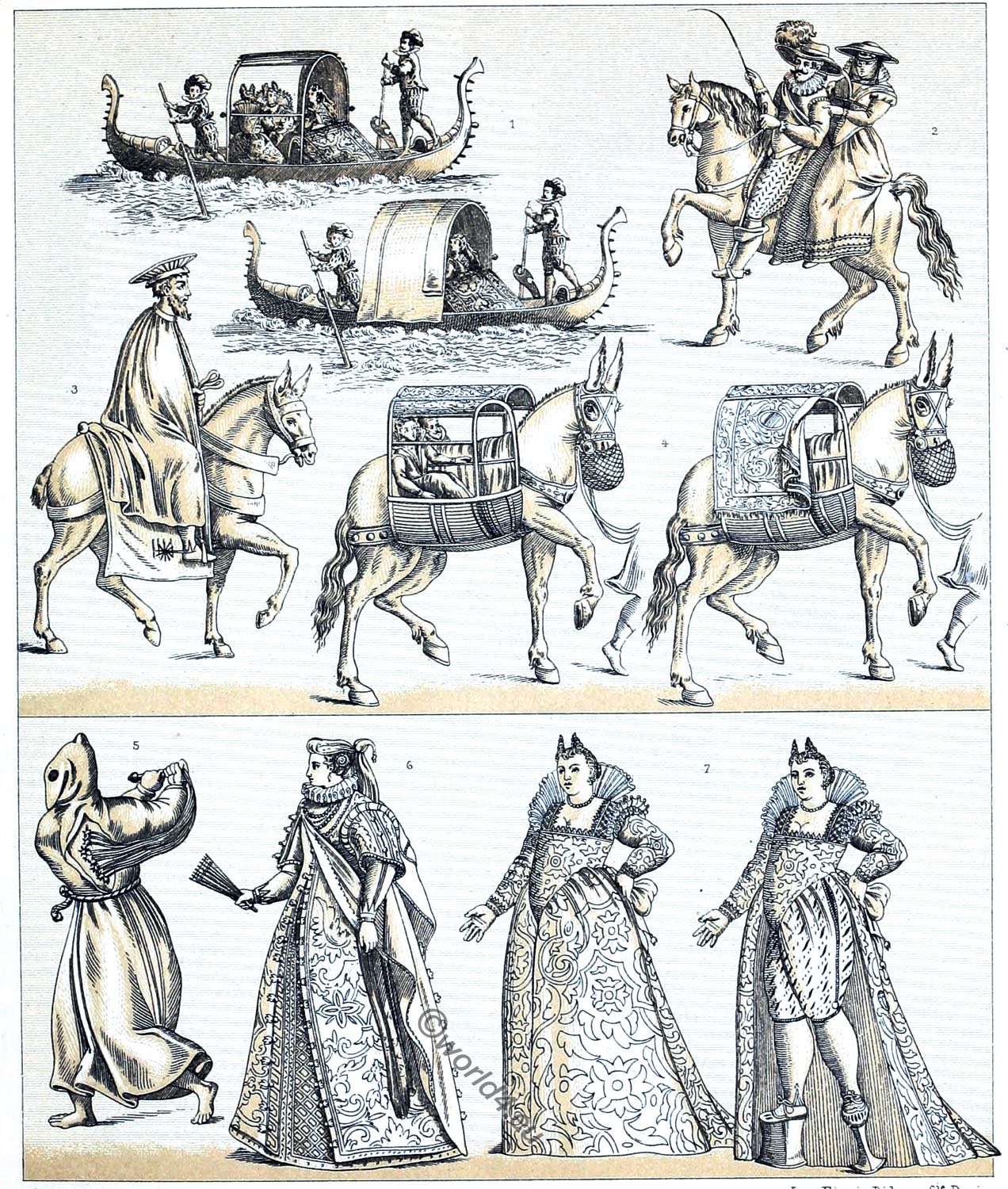

Although reluctant to go to Zametti, as if she had a premonition of evil, after a tender farewell from the King, Gabrielle embarked in a royal barge, which was attended by a flotilla of boats decorated with flags and streamers in the Venetian style.

On arrival in Paris, she was met on the quay by Zametti and a number of nobles and attendants, who escorted her to her lodging.

After sleeping the night, she arose early to attend Mass in a church close by, but before leaving the palace, Zametti presented her with an exquisitely decorated scent-bottle containing a strong perfume. During the service she fainted, and was carried back to the palace and placed at her own wish in the garden.

Another fainting attack followed, from which she was revived with difficulty. When she recovered, she ordered a litter to be instantly prepared, in which she was borne to the house of her aunt near the Louvre. Here she was put to bed and “lay with her eyes opened and turned upward, her face livid and her mouth distorted.” She called constantly for the King, but was too ill to write to him.

She was shortly seized with convulsions and died soon afterwards, it was believed poisoned by the perfume in the filigree scent-bottle, or by means of some food of which she had partaken while at the palace of Zametti.

Thus ended the romantic life of Gabrielle d’Estrées, but whether her death was due to the perfume or to natural causes we shall never know.

In 1548 the authorities of the city of Paris paid six golden crowns to one Georges Marteau for herbs and plants to perfume the public fountains on the occasion of a festival.

During the reign of Henry III the popularity of perfumes had so increased that in 1582 we find Nicolas de Montant reproving the women for using “all sorts of perfumes, cordial waters, civet, musk, ambergris, and other precious aromatics to perfume their clothes and linen, and even their whole bodies.”

Diana of Poitiers was one of the leading patronesses of perfumes and cosmetics of her time, and attributed the preservation of her beauty to their aid, and so was able to outshine all her rivals.

During the time of the Valois the use of perfumes among the higher class increased, but afterwards it appears to have waned until Louis XIII and Anne of Austria came to the throne, when the fashionable world again veered round in their favour.

Although Louis XIV is said to have discouraged their use at Court, according to Fournier, he had a great love for perfumes, and is described by him as “the sweetest-smelling monarch that he had everseen. ”He used to receive Martial, his perfumer, in his private closet to compose the odours he employed on his sacred person.

It was customary at that time for persons of rank and fashion to superintend the making of the special perfumes they favoured; thus the Prince of Conde always had his favourite snuff scented in his presence.

The names of distinguished people were often associated with both perfumes and cosmetics; thus the celebrated Poudre à la Maréchale, which was introduced about this time, took its name from Madame la Maréchale d’Aumont, who is said to have originated it.

During the Regency all the Court beauties used perfumes lavishly. Ninon de Lenclos claimed to have preserved her beauty until her sixtieth year by the aid of the wonderful cosmetics she constantly used, and the Du Barry, whose appearance suggested perennial youth, was said to have obtained the secret recipes for her toilet preparations from the notorious Cagliostro.

Perfume reached its zenith under Louis XV in the 18th century. His court was nicknamed “la cour parfumée” (the perfumed court). Madame de Pompadour ordered large quantities of perfume and the king requested to have a different fragrance in his apartment every day. Perfume was not only applied daily to the skin but also to clothes, fans and furniture, replacing soap and water. It was known “a la mode de Montpellier” because of the extra ingredients to enhance its fragrance.

Richelieu was a firm believer in the revivifying power of perfumes, and during his last illness insisted on sweet-smelling powders being diffused in his room by means of a bellows.

The household expenses of Madame de Pompadour at Choisy show her fondness for perfumes, the bills for which at one time amounted to 500,000 livres a year.

Marie Antoinette is said to have set the fashion in using the perfumes of violet and rose, which she preferred to the more powerful odours usually affected before her time.

The use of the perfumed bath, which Voltaire terms the “luxury of luxuries,” was revived towards the end of the eighteenth century. Madame Tallien favoured a bath of crushed strawberries and raspberries, after which she was gently rubbed with sponges soaked in perfumed milk.

The art of perfumery in France began to be studied scientifically towards the end of the seventeenth century, and the first work treating the subject from this point of view was published by Liebault in 1628.

Flowers began to be specially cultivated for the purpose of extracting their sweet odours, and the sun-warmed hills of the Var commenced to be famous for the production of the delicate and fragrant perfumes which are now known throughout the world.

Source: The mystery and lure of perfume by C. J. S. Thompson (1862-1943). Publisher London: John Lane, 1927.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.