THE IMAGES REPRESENT THE FOLLOWING IN THE MANUSCRIPT:

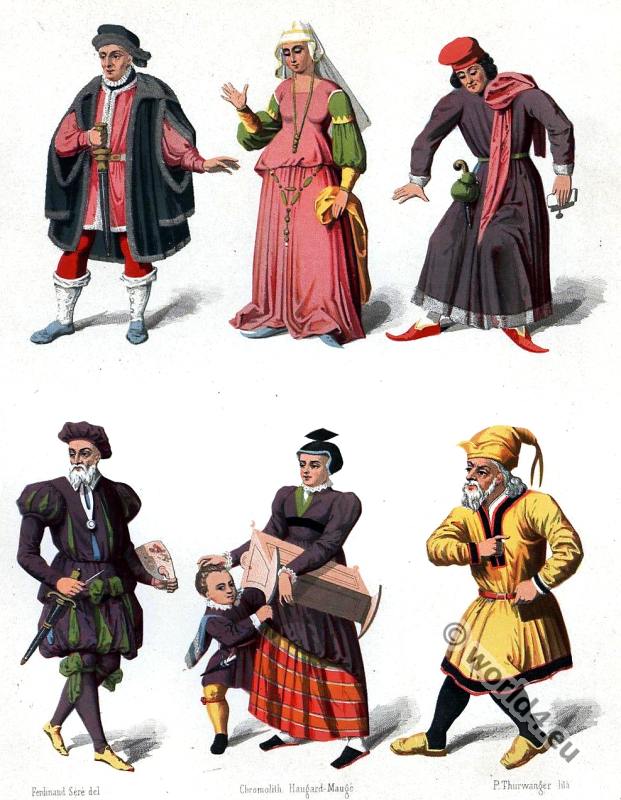

- No. 2. A sick queen, bleeding a knight in arms.

- No. 3. A shield-armed knight who draws his sword.

- No. 4. A squire (damoiseau).

- No. 5: King Arthur.

- No. 6 and 7. Queen Isolde, who is brought to the King of Cornwallis by a Knight of the Order of the Garter.

- No. 8. A knight in cloak.

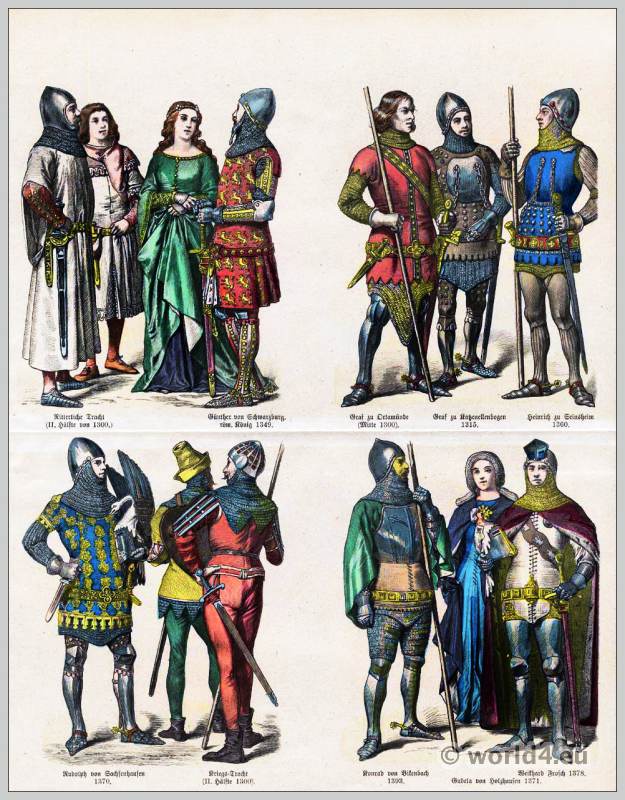

EUROPA. MEDIEVAL 14TH CENTURY. CIVIL AND WAR COSTUMES.

Medieval civil and war costumes of the 14th century.

The figures of this table are from an Italian manuscript of the XIVth century, a novel of the Holy Grail. (Mser. 6964 in the National Library of Paris).

The close costume of the 14th century appears in the north of France around 1340 under the reign of Philip of Valois. It had been worn in Marseille for a number of years, and according to the Italians, who gave it Catalan origin, it was common to all the cities of the Mediterranean Sea from Barcelona to Genoa.

In place of the long skirts came the tight and short jacket, which received the name jaquet or jaquette, and the pourpoint or gipon, a body skirt heavily lined with hair or tow, which served as an overskirt and could be opened at the front or sides. The leggings, which were fastened over the thighs, had feet, which were reinforced by socks and provided with soles. In good weather no shoes were needed, in bad weather wooden or iron-fitted galoshes were tied underneath.

These footwear were pointed, and this point gradually became longer and longer. It was supported by whalebone and was not missing from the ordinary shoes and boots, nor from the knights’ greaves. These shoes were called poulaines (beak-shaped shoes), an expression derived from polonaises.

After they had gone out of fashion in Western Europe, they reappeared in Poland and returned from there to the West as a novelty. The English called them crakowes (Krakowers). In the 14th century, beak-shaped shoes took on such unusual dimensions that even their tips were bent over to allow walking and attached to the shin with a string.

Knights and squires also adopted the habit of dressing their legs in two different colours: one leg was white, yellow, green, the other black, blue or red. They even wore shoes of different colours. This type of multi-coloured division of clothes was called Mi-Parti.

The state costume of judges, lawyers, scholars and similar persons, who wanted to document a certain dignity in their outward appearance, retained the wide overcoats and cloaks in contrast to the tight costume of the dandies. The men were then divided into two classes: the gens de robe courte and the gens de robe longue.

The costume we depict was common in Italy, France and England at the same time. The jacket has only half sleeves up to the elbow, whereas the sleeves of the skirt reached up to the wrist. To make them fit better, they were buttoned from the elbow on.

The jacket had to cling so tightly to the body that it did not crease. Therefore the fabric was padded and stuffed around the body. This padding gradually developed into a kind of hump, which soon took on a large size and was called a goose belly. The belt was worn below the hips, sometimes just above the border or on the edge of the jacquet itself; only the dagger was attached to it.

The Jaquet is closed at the front by a row of buttons, the buttonholes are sewn with silk. The jacquard was not decorated with embroidered coats of arms at that time. However, you can see from our illustrations that the initials of the wearer (in the case of King No. 5) and geometric figures in silk and pearls were sewn or embroidered on the fabric.

Pearls were then worn everywhere, on belts, crowns, hats and even on shoes. The leg dresses were made of cloth; particularly in use were the scarlet (écarlate) of Brussels, the yreigne, a thin spiderweb-like fabric of Ypres (Belgium) and other fabrics from Rouen and Montivilliers.

The headgear of No. 4 consists of a hood and a stiff, conical hat that is placed on top of it. The ostrich feather was a rarity at that time, which was balanced with gold.

The coat of No. 8, which is open at the side, was called a Tabard (cloche), which corresponds to the German name Hoike (heuke). The Tabard was a sleeveless, bell-shaped, almost calf-length cloak of the Middle Ages, which was closed over the shoulder for men, but put over the head for women. It was worn from the 13th century onwards, but particularly frequently by men at the beginning of the 14th century, when fashion shifted to richly woven garments. A special example was the Spanish version, which was hooded. The Tappert is identical with the Houppelande from France and Burgundy. The Tappert was worn in numerous variations, half-long and long, sleeveless and open at the sides, with wide arm slits or with sleeves of varied, extensive shape.

Around 1340, under Philip of Valois, the war dress and armour had also undergone a complete change. The weapons skirt reached only down to above the hip, and the whole costume became tightly attached. The front of the body is protected by plates which are attached to the mesh shirt with straps. The joints of the shoulder and elbow are protected by round plates. The thighs are covered with boiled leather leg splints, which also receive special knee protection. The thighs are also protected by steel plates, as are the forearms, which are inserted into complete iron tubes (called canons).

Even the footwear, which, as already noted, followed the uncomfortable fashion of poulaine shoes, was made of movable steel plates. The helmet, the bascinet (also Bacyn, bassinet, basinet, or bazineto), was not put on the striped hood, as in former times, but directly on the head. The hood serving as neck protection was only attached to the lower edges of the helmet. The face was protected by an iron mask with holes to see and a bulge to accommodate the nose, which was attached to the helmet by a hinge.

This mask is the visor that remained in use for a long time. Around 1300, the hood was separated from the gorget. At the same time the custom of helmet decorations, the crest (cimiers) appeared. With time, they took on grotesque forms and large dimensions. There were those of two feet height. The fingers of the iron gloves are jointed as well as the feet. The wheel spur was in use since the end of the 13th century.

The knight put on the gorget first, because the armour was fastened to them with straps. The helmet made the end. It was provided with a fold, and this connected it directly to the gorget or the ring collar, so that the head could be moved sideways. It also had a chin piece and a neck umbrella, the former was fastened to the neck mountains with a hook and thus held the helmet. Chin piece, mouthpiece and visor were held together by a screw at the helmet and were fastened under themselves by hooks. The omission of this hooking at a tournament cost the life of Henry II, King of France, on 10 July 1559.

The main piece of clothing for women at that time was the cotte hardie, a close-fitting, short-sleeved skirt, which made the body shapes stand out plastically. These skirts were decorated with trimmings on the neckline, sleeves and shoulders. The hair was parted in the middle and then fell loosely onto the back.

The Litter (palanquin) was an open or roofed bed, which was carried by two horses. It was mainly used by women and sick people and also served to remove the wounded from the show grounds.

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Albert Charles Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.