EVERY English cathedral is famous for someone feature connected with its building, position or history which gives it its own peculiar charm. The west-front of Peterborough, the position of Durham, the calm beauty of Wells, each gives the individual character which is such a delightful feature of our great churches. At Canterbury it is the historic associations of the cathedral and its archbishops which appeal most strongly to every visitor as he approaches through the quaint narrow street and stately gateway.

The history of the see is practically the history of the Church in England, and very largely of the English people. As we glance through the list of primates there rise before us scenes which have made the history not only of Britain but of Europe and the world. Augustine, Dunstan, Lanfranc, Anselm, Langton, Chichele, Cranmer, Laud, Sancroft — what strivings, what victories, what disappointments such names recall! The rise of the people, the spread of learning, the reform of the church, the growth of the constitution, all are intimately bound up in the lives and doings of the archbishops.

But among such an army of great and wise men two stand out far above all others when we think of Canterbury—Thomas Becket, martyr and saint; Edward, the Black Prince, the national hero of the age of chivalry. These two surpass all others in the romantic associations which their names recall and claim a first place in the affections of all English-speaking people.

The importance of St. Thomas in the medieval world was immense. Canonised three years after his death heat once became the most popular saint in Europe. A vast revenue flowed into the monastery, and the choir, the longest in England, was built to accommodate the eager throngs of pilgrims. Kings and Emperors came to implore his aid or to return thanks for his protection, and even Henry the Eighth, the ultimate destroyer of the magnificent shrine, did not neglect to come and bring his imperial guest, Charles V.

The cathedral stands on the site of the Roman basilica which was given to St. Augustine by King Ethelbert in 597. Various additions and alterations were made before this church was finally swept away in 1067 and Lanfranc began his cathedral. It was not til the rebuilding of the north-west tower in 1840 that the church reached its present state after a lapse of nearly eight hundred years. Christ Church was once part of a great Benedictine monastery founded by Lanfranc. Of the monastic buildings many beautiful fragments remain, but none more beautiful than the stairway near the northern entrance to the Close. As an example of Norman domestic architecture it is unrivalled.

Canterbury by Arnold Fairbairns.

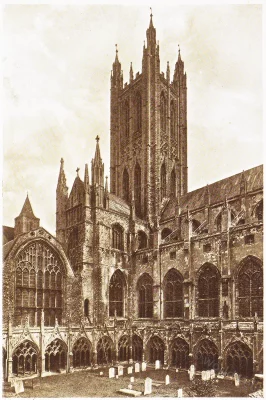

THE CATHEDRAL, FROM CHRIST CHURCH GATEWAY

AS it stands to-day Canterbury cathedral covers almost exactly the same ground as Lanfranc’s church. The only noticeable addition is the east end, which was greatly extended after “the glorious choir of Conrad” had been burned down in 1174. The small square towers built into the eastern transepts are the most striking remains of this earlier building, and give some idea of the wealth of carving which made it so famous.

At the west end Lanfranc’s towers have been replaced by later builders in the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Of remarkable beauty is the turret of the south transept.

THE CENTRAL TOWER FROM THE CLOISTERS

THE Bell Harry Tower, built by Prior Goldstone in 1495, is the crowning glory of the cathedral. It is 235 feet high, only surpassed by Lincoln which is 271, and being placed in the midst of an unusually long, low church, gains immensely in dignity. The name Bell Harry is given it because of the great bell of three tons and three hundredweight which hangs in it.

The chapter house and cloisters are the work of Prior Chillenden in the fifteenth century. The latter were originally glazed, as at Gloucester, and were the scene of much of the daily work of the monks.

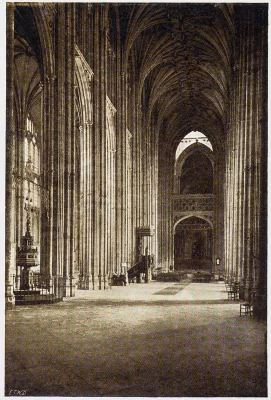

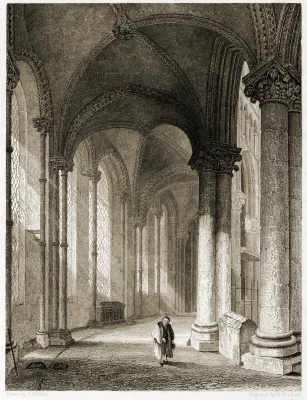

THE NAVE

ENTERING by the south-west porch the nave is seen stripped of all the beautiful colour and glass which once covered its splendid columns, and filled its great windows. Now all is bright and glaring, but the contrast which results between the nave and the dimly lighted choir is as impressive as anything in our cathedrals. Prior Chillenden in the latter half of the fourteenth century rebuilt the nave, the curious buttresses of the central tower being added in 1425.

The body of Archbishop Benson lies in the north aisle. He was the first primate buried in the cathedral since Reginald Pole, the great archbishop of Queen Mary’s reign.

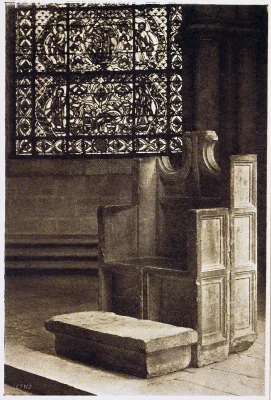

ST. AUGUSTINE’S CHAIR

THE name which is given to this ancient chair recalls the first Roman missionary to Kent, St. Augustine. The little church of St. Martin, a mile away, is perhaps more closely associated with his memory, but it must be remembered that Christ Church was his foundation.

The chair is the cathedra or bishop’s seat which gives the church its title and position. Though of very great antiquity it is almost certainly not contemporary with St. Augustine. Every archbishop is enthroned in this chair on his elevation to the primacy.

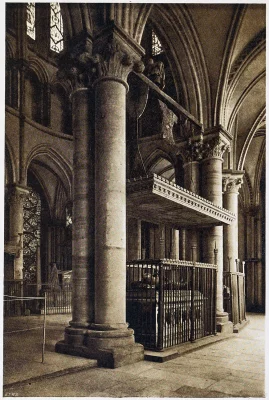

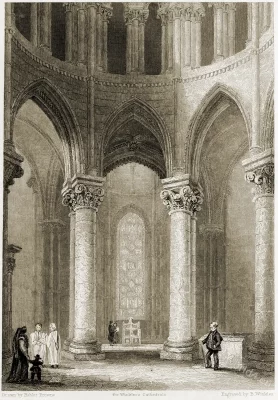

THE CHOIR

TO the antiquarian the choir is profoundly interesting on account of its very foreign character, quite unlike any contemporary work in England. William of Sens, who was the architect of the western part, was greatly influenced by the traditions of his native town, and his successor, the English William, was naturally bound to finish his work in the same style. The strange variations in width are due to the desire to retain the fragments of Conrad’s choir which had survived the fire of 1174.

Prior d’Estria built the beautiful enclosing screen, a thoroughly English work of the early fourteenth century.

THE BLACK PRINCE’S TOMB

ASCENDING the steps worn by the knees of countless pilgrims to Becket’s shrine, the Trinity Chapel is entered.

The tomb of Edward, the Black Prince, is undoubtedly the most interesting monument which remains in the cathedral. A bronze figure of great beauty represents the warrior in full armour, and the tomb bears the familiar badge of the Prince of Wales, together with an epitaph written by Edward himself. On the beam above is part of the suit of armour worn in actual warfare.

In this chapel Henry IV lies buried, and the vacant space in the middle is the site of the shrine of St. Thomas. The glass in the aisles is the finest of the period in England.

THE MARTYRDOM

THE north-west transept, the site of Becket’s tragic death on December 23, 1170, is perhaps the most strangely fascinating spot in any English Church. The great reconstruction of the fourteenth century has, it is true, altered the appearance of this corner but, perhaps designedly, the very place where the saint fell remains undisturbed to this day. Part of the cloister doorway belongs to the one through which the archbishop entered the church a few moments before his death.

The great window in the north wall was given by Edward IV, and contains portraits of Edward V and his brother who were murdered in the Tower of London.

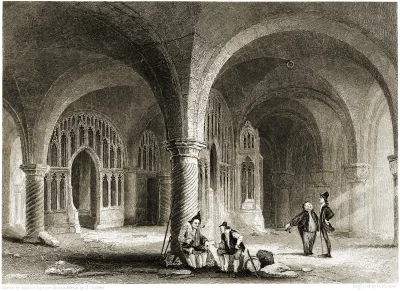

THE CRYPT

IN the crypt some of the earliest work of the Norman builders is seen. The west end, which is here illustrated, was built by Conrad and survived the fire of 1174. The capitals are beautifully

carved, though only partly finished in some cases. English William built the eastern portion to support the Trinity Chapel.

The Lady Chapel, which was of extraordinary magnificence, was in the crypt, and here Henry II performed his famous penance at the tomb of Becket before the saint was translated to the chapel above.

The whole crypt was granted by Elizabeth to Huguenot refugees for their looms, and a French service is still celebrated in their special chapel.

CANTERBURY CATHEDRAL.

by John Tillotson

The archiepiscopal see of the primate and metropolitan of all England was established in the year 597, by Pope Gregory the Great, who sent the pall to Augustine. The province of Canterbury includes the bishoprics of Bangor, Bath and Wells, Bristol, Chichester, Lichfield and Coventry, Ely, Exeter, Gloucester, Hereford, Llandaff, Lincoln, London, Norwich, Oxford, Peterborough, Rochester, St. Asaph, St. David’s, Salisbury, Winchester, and Worcester.

The province of Canterbury was finally settled by Pope Leo III., A. D. 803, when he denounced everlasting damnation against all who should attempt to tear the coat of Christ. The arms of the archiepiscopal see represent the staff and pall, insignia formerly of great importance.

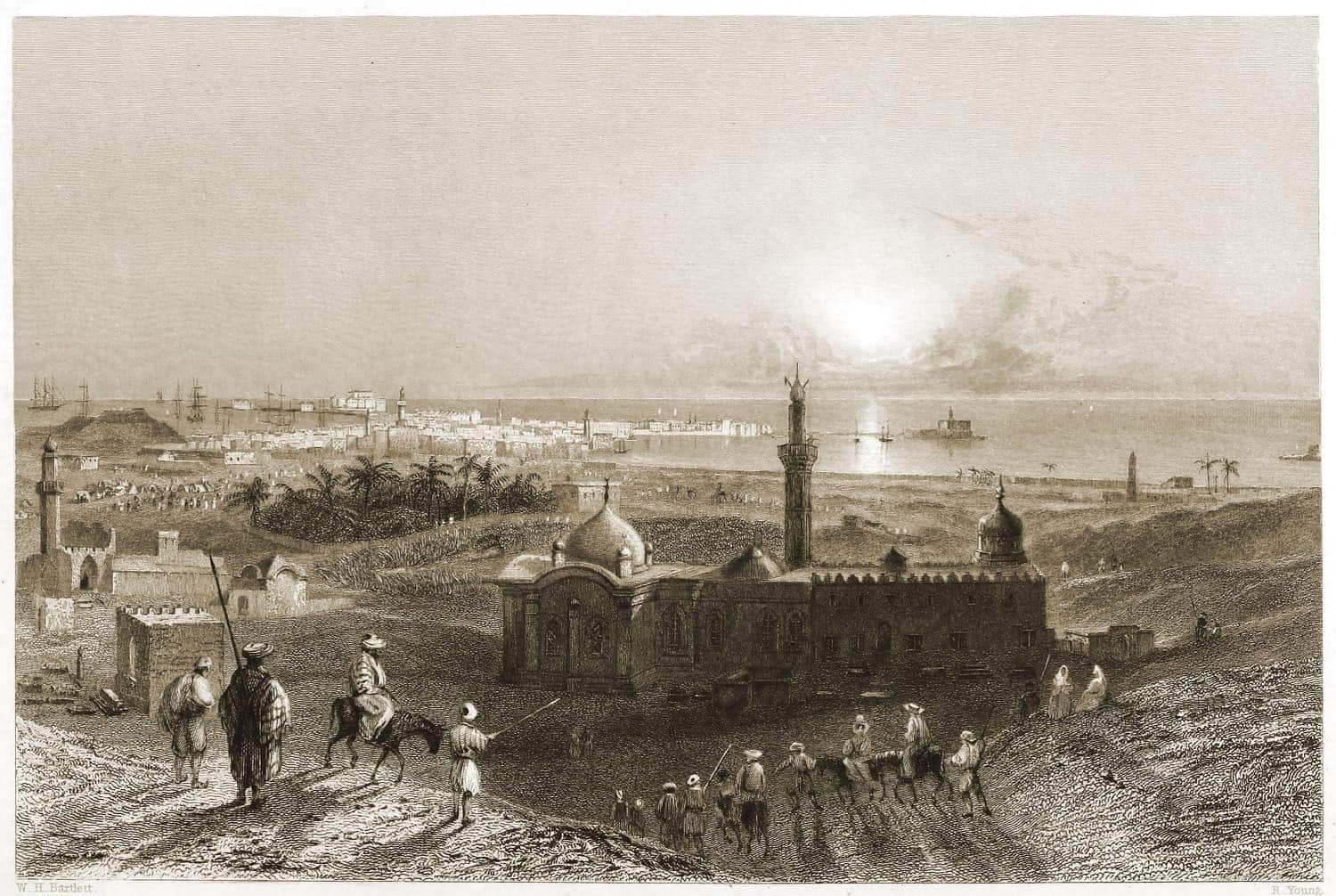

The ancient city of Canterbury, (the ecclesiastical metropolis of England) is chiefly remarkable for its churches, especially for its magnificent Cathedral, which is seven centuries old, and occupies the site of the first Christian edifice erected in England.

“The deep-set windows, stained and traced,

Would seem slow flaming, crimson fires

From shadowy grots of arches interlaced,

And tipt with frost-like spires.”

The choir is the most spacious in the kingdom; the nave, cloisters, and chapter-house are excellent architectural specimens of the early pointed style—the central tower is 235 feet high, the length of the church is 513 feet—all of which, with many more particulars of the same kind, are duly chronicled in the guide books.

But is it not a fact that the exact height, depth, length, and breadth of great buildings conveys a very inadequate idea to the mind of what the building really is, that in looking on the time-worn towers, the fretted roofs, the graceful sweep of arches supported by clustering pillars, all exhibited to us in the l dim religious light stealing through the stained windows and flinging on the marble pavement masses of purple, gold and red, that we forget all about the dimensions of the edifice, all that guide books have to relate, all that a garrulous verger rotes in our ear.

The mind looks back—historical memories are revived—the great ones of old—priests and princes move before us; we see with the mind’s eye shadowy but stately forms, the master spirits of a bygone age—and the men of mail and mitre play out their parts before us.

Here in Canterbury Cathedral, two churchmen, divided from each other by six hundred years, are brought together. Here we think of Augustine, who came hither as missionary from Rome, and being favourably received by the Saxon King of Kent, repaired to the capital town, called Kent-wara-byrig (Cant-wara-byrig), since corrupted into Canterbury.

The missionary band entered it in procession, carrying the cross, pictures and relics, and chanting litanies, and established themselves in a church built by the Christian Britons, but abandoned in the days of persecution which followed the setting up of the Saxon government.

Here they celebrated mass and made many converts, so that Augustine wrote to the Pope, saying—”the harvest is plenteous, and the labourers no longer suffice.” Augustine accommodated himself and his faith to the habits and customs of the idolatrous Saxons.

Their temples were not destroyed but sprinkled with holy Water, and christened by saintly names; their sacrifices were not forbidden, but were to be regarded as Christian banquets to the honour of God, and not as offerings to idols; their festivals were not to be abandoned, but to be associated with the memory of saints and martyrs: everything remained as it was, only under different names.

A shrewd man of the world was this austere monk Augustine, first Archbishop of Canterbury, a man of kindred spirit with that other Archbishop who was murdered centuries afterwards on the altar steps of the Cathedral.

Look yonder, in imagination, and conjure up a gaily attired hawking party of the twelfth century gallantly mounted, bravely attired, they ride; with hawk and hound to dark pools, where the reeds spring up long and dank. Who is it laughs the loudest, utters the wittiest repartee, whispers the softest nothings in my lady’s ear, casts off his bird and brings down the prey the readiest? It is the young Englishman, Thomas Becket, who does not seem to have in him the makings of a sanctified prelate.

But the church is the road to his preferment, and he takes it readily. A change comes over him; he is a devout looking monk, a man of vigil and fasting, of self-humiliation and self-discipline: he rises rapidly, and another change comes over him. Now he is the haughty bishop, the king’s intimate companion, surpassing the Norman courtiers in luxury and lordly pomp.

Seven hundred horsemen, the harness of their chargers embossed with gold and silver, are kept in his pay. His ambition rises higher each day, but the ascent is dangerous; the King takes alarm, murmurs, half suggests he would be rid of him, and the rest is easy. Soft and sweet rise the rich strains of music; white robed priests are sweeping past, and incense bearers swing their silver vessels and perfume the air.

Yonder stands Becket at the altar for the last time. Four armed men have struck him down, with yells and oaths have bidden him die, and have given him his death blow. They have fled on the completion of their murderous work, and crowds of people have surrounded the corpse stretched across the steps of the high altar—weeping, kissing its hands and feet, dipping handkerchiefs in the blood that covers the pavement.

So Bishop Becket becomes Saint Thomas. A crowned king whose hasty word has caused his murder, is stripped and flogged; pilgrims from all parts of England visit the shrine of the new saint: and the practice is maintained for near four hundred years. This annual pilgrimage—of which Chaucer has sung—was suppressed at the time of the Reformation.

The saint’s grave remains one of Britain’s most important and largest pilgrimage sites.

Source:

- Beauties of English scenery: illustrated with thirty-five engravings on steel, from designs by W. H. Bartlett, D. Cox, W. Daniell, R. A., H. Gastineau, C. Bentley, G. Shepherd, T. M. Baynes, &c. by John Tillotson (ca. 1830-1871). London: Allman & Co. 1860.

- Winkles’s architectural and picturesque illustrations of the cathedral churches of England and Wales by Benjamin Winkles, Robert Garland, Thomas Moule. London: Effingham Wilson, Royal Exchange, and Charles Tilt, Fleet Street, 1836.

- The “Dainty” portfolio of English cathedrals: Canterbury by Arnold Fairbairns. London: E.T.W. Dennis, 1900.

Related

- Ely Cathedral in Cambridgeshire, England.

- Nave of Wells Cathedral. Main work of early English Gothic architecture.

- Glastonbury Abbey in the county of Somerset, England.

- The market cross at Glastonbury, Somerset.

- The Gloucester Cathedral.

- The cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris.

- Monasteries and Cloisters as Centres of learning and Culture.

- Rouen Cathedral coronation site and burial place of the Norman dukes.

- Figures of Ecclesiastics of the cathedral of Chartres.

- Tintern Abbey. An excellent specimen of pure Gothic architecture.

- The cloisters of Belem. The Mosteiro dos Jerónimos. Lisbon, Portugal.

- The Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, also known as Jerome Monastery, Lisbon.

- Al-Andalus. Interior of the Mosque at Córdoba, Spain.

- Pilgrimages and the sacred hills of Buddhism in China.

- The Laura of Mar Saba near the Dead Sea.

- Convent of Mar Saba. The Holy Laura of Saint Sabbas. Palestine.

- The Franciscan Convent of the Terra Santa, Nazareth.

- Early monastic life and the controversy over icons.

- The daily life of the monk favourable or detrimental to creative work.

- The Holy House of Loreto. The Basilica della Santa Casa.

- The convent of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai, Egypt.

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.