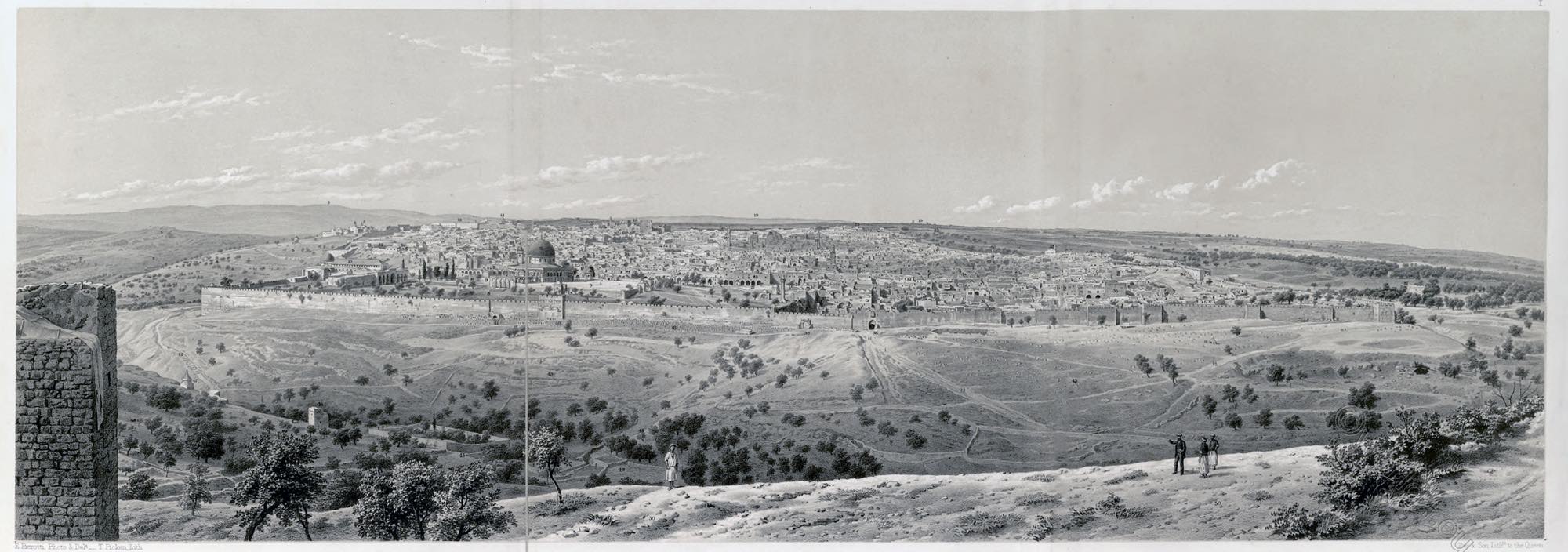

PLATE XLV.

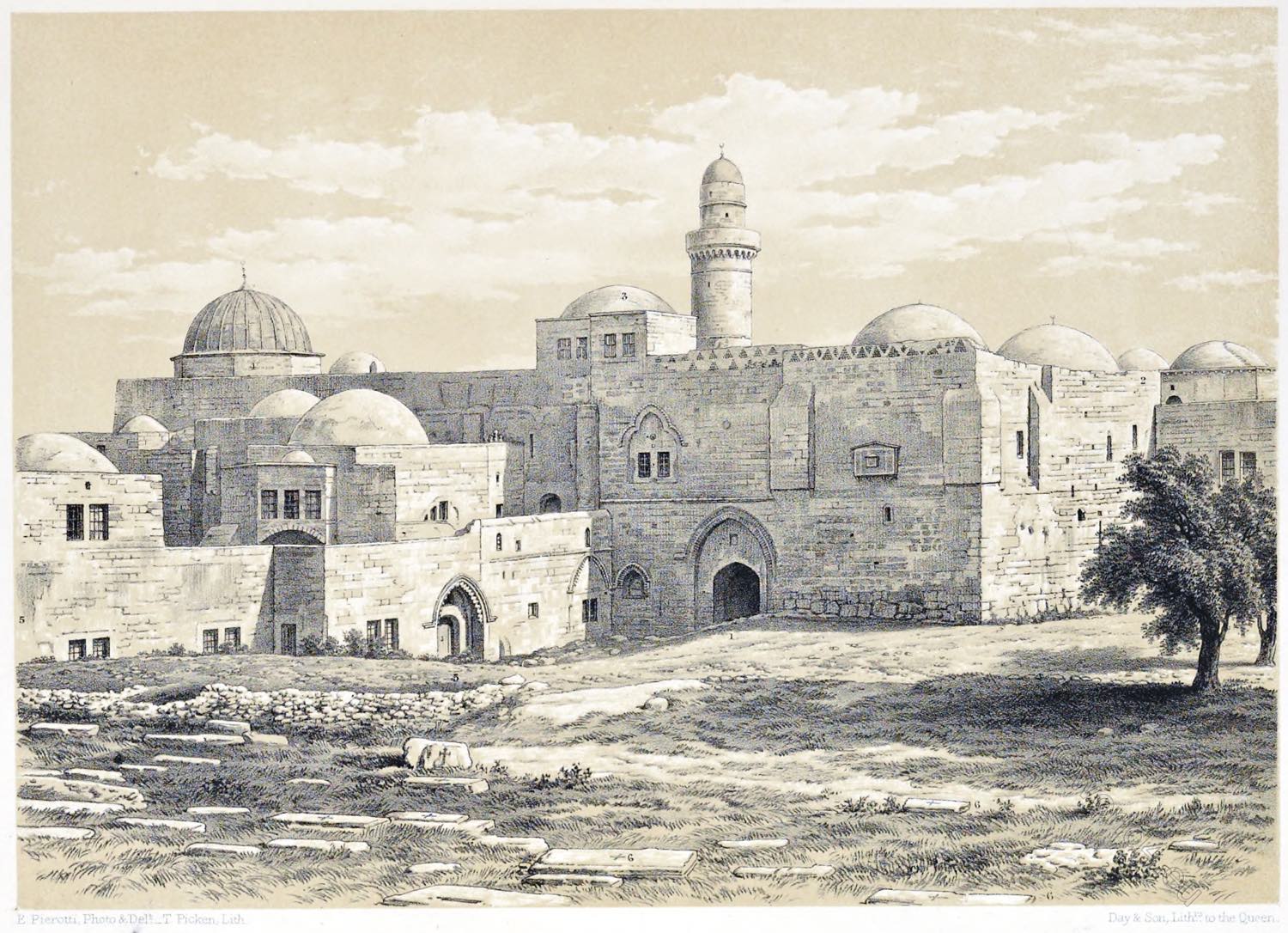

VIEW OF THE CENACLE (COENACULUM), AND OF THE SO-CALLED TOMB OF DAVID.

- Principal Entrance.

- Mohammedan Houses.

- Cenacle (Coenaculum).

- Dome of the Tomb of David.

- Modern Mohammedan Houses.

- Christian Cemetery.

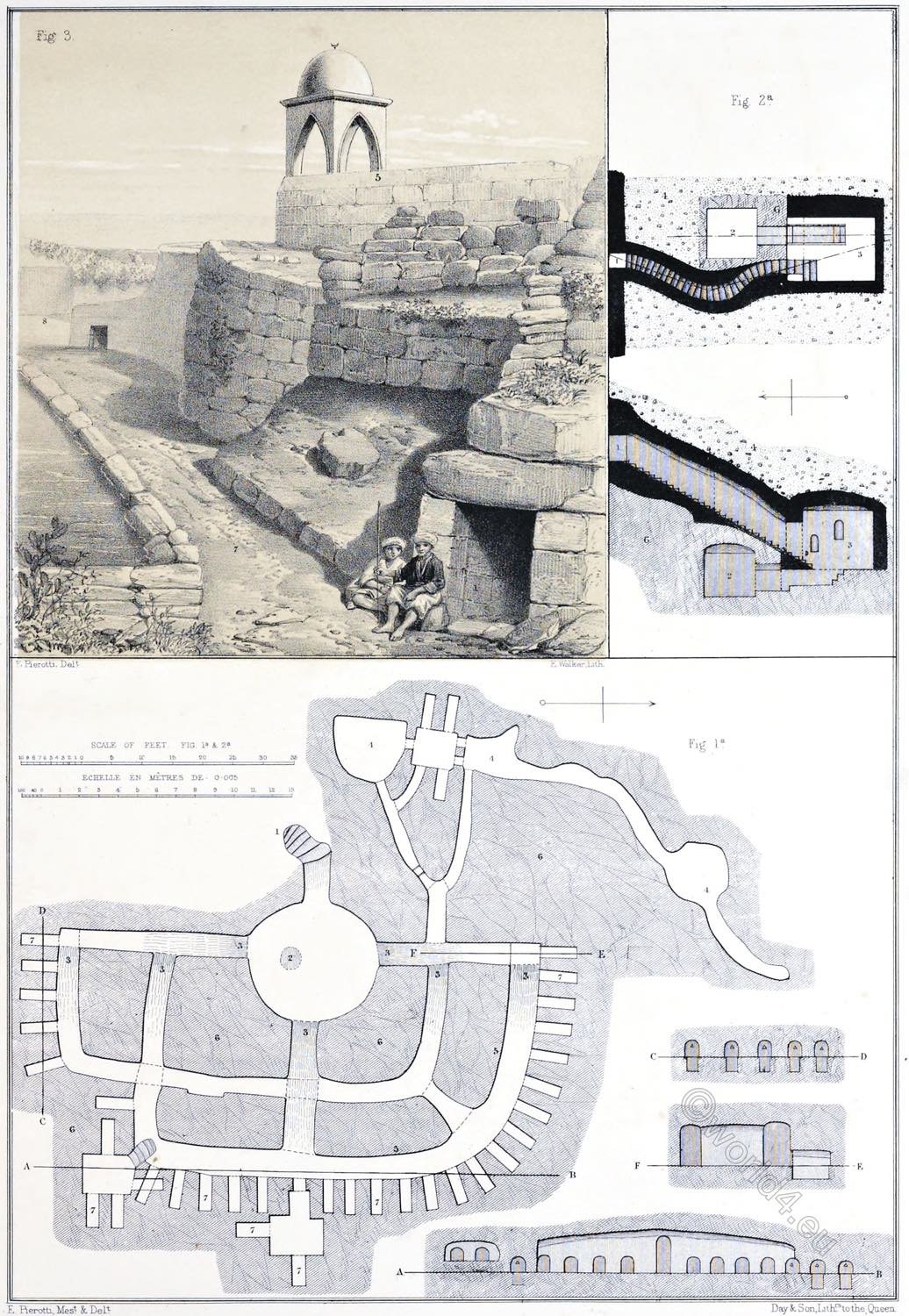

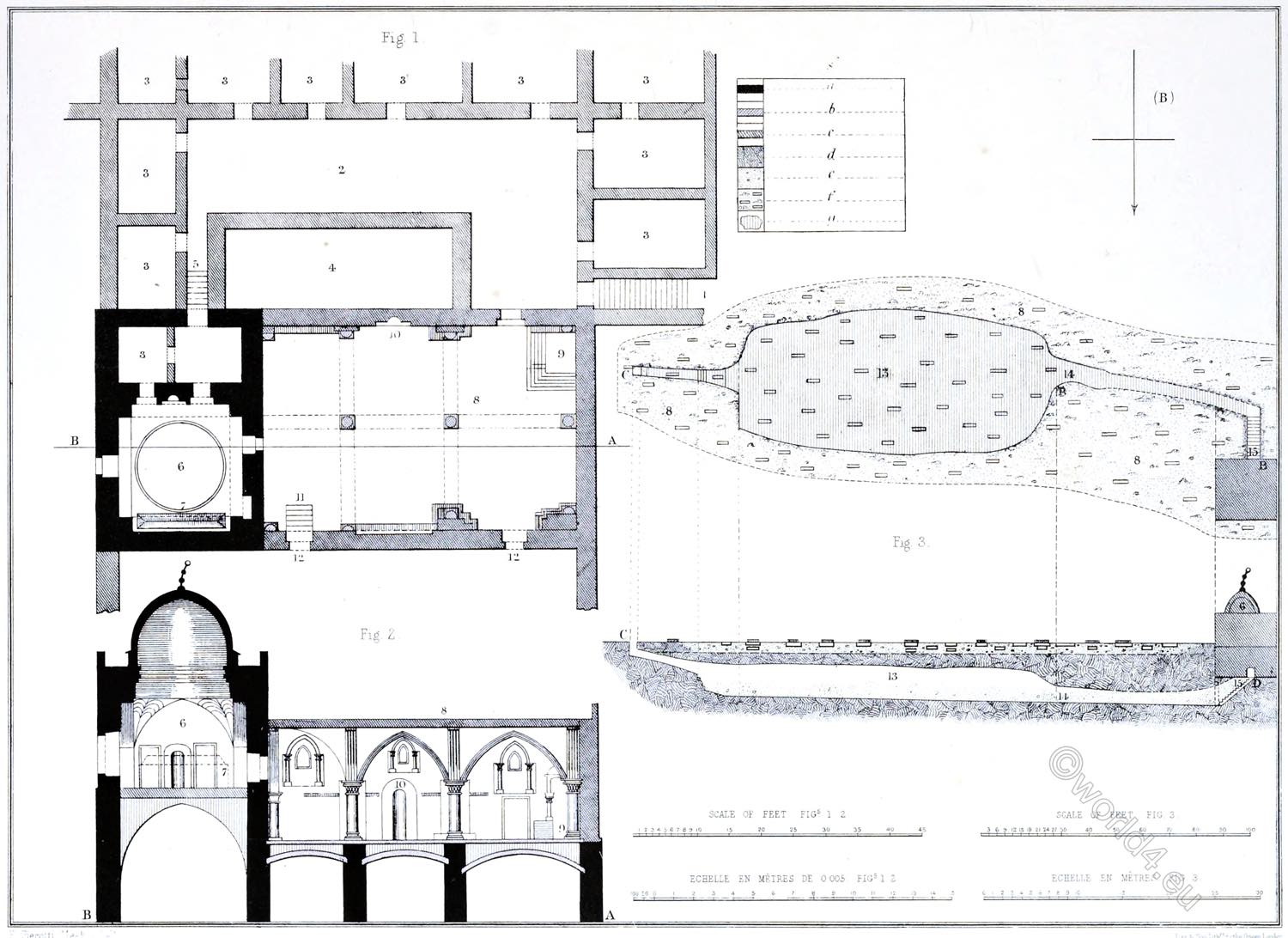

PLATE XLVI.

PLAN AND SECTION OF THE CENACLE (COENACULUM); OF THE SO-CALLED TOMB OF DAVID; AND OF THE UNDERGROUND WORKS OF MOUNT SION.

- Staircase leading to the Upper Court,

- Upper Court.

- Mohammedan Chambers.

- Lower Court.

- Passage to the Tomb of David.

- Mohammedan Chapel, dedicated to the Tomb of David.

- Representation of the Sarcophagus of David.

- Cenacle (Coenaculum).

- Staircase leading to the Tomb of David.

- Place of the Mohammedan Priest.

- Staircase leading to upper Chambers.

- Chambers.

- Underground Works of Mount Sion, in front of the Tomb of David.

- Subterranean Passage covered with stone and earth.

- Staircase leading to underground Works.

S. Conventional Signs.

a. Ancient Wall.

b. Wall of the time of S. Helena, or of the Crusaders.

c. Modern Arab Wall.

d. Rock.

e. Place covered with earth.

f. Christian Tombs.

g. Underground Works.

Source: Jerusalem Explored. Being a description of the ancient and modern city, with numerous illustrations consisting of views, ground plans, and sections by Ermete Pierotti; translated by Thomas George Bonney (Fellow of St Johns College, Cambridge). London: Bell and Daldy; Cambridge: Deighton, Bell and Co. 1864.

THE CENACLE (Coenaculum).

This term generally refers to the place in Jerusalem where Jesus had the Last Supper of his earthly life with the Apostles before dying on the Cross. Later, the Apostles gathered there after Jesus’ resurrection (cf. Gospel according to John 20:19-29) and at Pentecost (cf. Acts of the Apostles 2:1-4).

Cenacle (Latin: coenaculum) indicated in itself the place where one dined, but more generally it designated the upper floor of the house accessed by stairs. According to ancient Roman custom, it was always a rather large room and was used for dinner, which was the main meal of the day, attended by all the family members and any guests present.

In the context of the Gospel narrative, this means the upper floor of the house because it translates the corresponding Greek word ἀνάγαιον, anágaíon (cf. Gospel according to Mark 14:15; Gospel according to Luke 22:12), which indicates, precisely, the upper and hospitable part of the house.

Documents show that the church was rebuilt or restored in the second half of the 4th century by the Bishop of Jerusalem, John II (386-417); the festive sermon has been preserved and can (probably) be dated 15 September 394. Since then it has been called “Holy Sion”. Some precious relics of the Passion were venerated there: the Communion cup as well as the lamp in the light of which Jesus taught his disciples, and the memory of St James and King David, whose tomb was venerated under the Cenacle, was celebrated. From this meaning he moved to a topographical designation, calling the southern part of the western hill on which the Upper Room stands “Mount Zion”. The competing localisation on the Mount of Olives was suppressed.

The militia of Khosrow’s II Persians destroyed the church in 614; many Christians sought shelter in vain in the Hagia Sion Basilica; more than 2000 people were killed around the church, and the church was also set on fire. It was restored a few years later by the monk Modestus, later Patriarch of Jerusalem. It was later devastated again by the Muslims. On their arrival the Crusaders found the ruins of the holy place: only the chapel of the Cenacle had been saved. They built a great basilica that included not only the ‘Upper Hall’ (the Chapel of the Cenacle) but also the site of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary.

According to the pilgrim Arculf *), traditions of the Passion story were also added with the scourging column (Christ at the Column or the Scourging at the Pillar); Arkulf is credited with a plan of the church which shows that the south-east corner of the basilica was venerated as the place of the Last Supper: Locus hic caenae domini, “Here (is) the place of the Lord’s Supper.”

*) Arculf (born in the 7th century) was, according to his own account, a Frankish bishop in the 7th century who was influenced by Gallo-Roman culture. The account of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land is an important historical source about the Middle East shortly after the Islamic conquest.

After the fall of the Crusader reign, the cenacle was preserved by the Christians who continued to celebrate Mass there, while the basilica gradually fell into disrepair. In 1219, however, the church building was demolished by the Muslim defenders of Jerusalem for strategic reasons. The participants of the 5th Crusade found a ruin with the tombs of David and the other kings on the ground floor and the Upper Room on the upper floor.

A restoration in the years 1229 to 1244 produced the building that still exists today. “The other traditions had attached themselves to different parts of the ruins, creating something like a religious garden with the old legends of Mount Sion.”

The arrival of the Franciscans in the Holy Land in 1333, following the purchase of the Cenacle that the kings of Naples, Robert of Anjou and Sancia contracted with the Sultan of Egypt, saw, as a first work, the restoration of the Cenacle and the construction, a few years later, of the adjacent, small convent that is still preserved today. It was then that the superior of the Franciscans in the Holy Land assumed the title of “Guardian of Mount Sion”; but they had to leave Mount Zion altogether in 1551.

A century later, Muslims and some Jewish families appropriated the rooms below the Cenacle, claiming for themselves the ‘Tomb of the Prophet David’.

A century later, the rooms below the Upper Room of the building passed to the Muslim community and some Jewish families as a sanctuary in honour of the Prophet David (Nebi Daˤud), and was given a minaret.

The Upper Room could still be visited by Christian pilgrims for a fee. Today, Franciscans of the Custody of the Holy Land live again in a convent near the cenacle.

A British Mandate regulation grants access to the holy site to members of all religions, but severely restricts worship. While Christian visitors often recite a psalm or sing a hymn here, services are only allowed three times a year, and no Christian symbols (such as crosses) are seen in the space.

Another tradition, however, places the site of the cenacle at the home of St Mark’s mother, where the Church of St Mark, belonging to the Syriac Orthodox Church, now stands.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.