THE PEASANT ART OF LITHUANIA.

THE manifold influences to which Lithuania has been subjected in the course of centuries sufficiently account for the characteristic diversity of the basic elements in its peasant art as a whole. This “Volkskunst” (Folkart) forms a conglomeration of various ethnographic elements which frequently present sharp contrasts.

Beginning with an ornament that is reminiscent of Roman bronzes, there are to be found in this peasant art, derived from a common pre-Aryan source, more or less numerous traces of Finnish, Scandinavian, Germanic, Oriental, Byzantin-Russian, West Polish and other influences, some of which are still existent, while others have already vanished. And since these manifold influences have not operated for the same length of time and with the same intensity in all parts of the country, it has resulted that the peasant art of each of these parts has acquired certain particular traits not only in regard to form, but also in respect of technique and material. On the other hand, however, the general character, physical and mental, of the native inhabitants, has impressed a common stamp upon the entire peasant art of the country, and in consequence, in spite of racial affinities with other countries, the artistic productions of Lithuania as a whole have acquired a distinct and independent character, both as regards conception and a certain archaism and primitivism of execution.

The artistic activity of the Lithuanians has in the main manifested itself in three directions-in weaving, in the ornamentation of their household utensils of wood, and in their so-called “chapel crosses” or wayside shrines. Their architecture I will pass over, as it does not present any specially characteristic traits, and as a whole cannot, with the exception of a few carvings on roofs, balconies, and window-frames, mostly adopted in recent times from neighboring peoples, be regarded as the actual creation of the Lithuanians, in this respect offering a marked contrast to an architecture like that of the Polish inhabitants of the Tatra mountains.

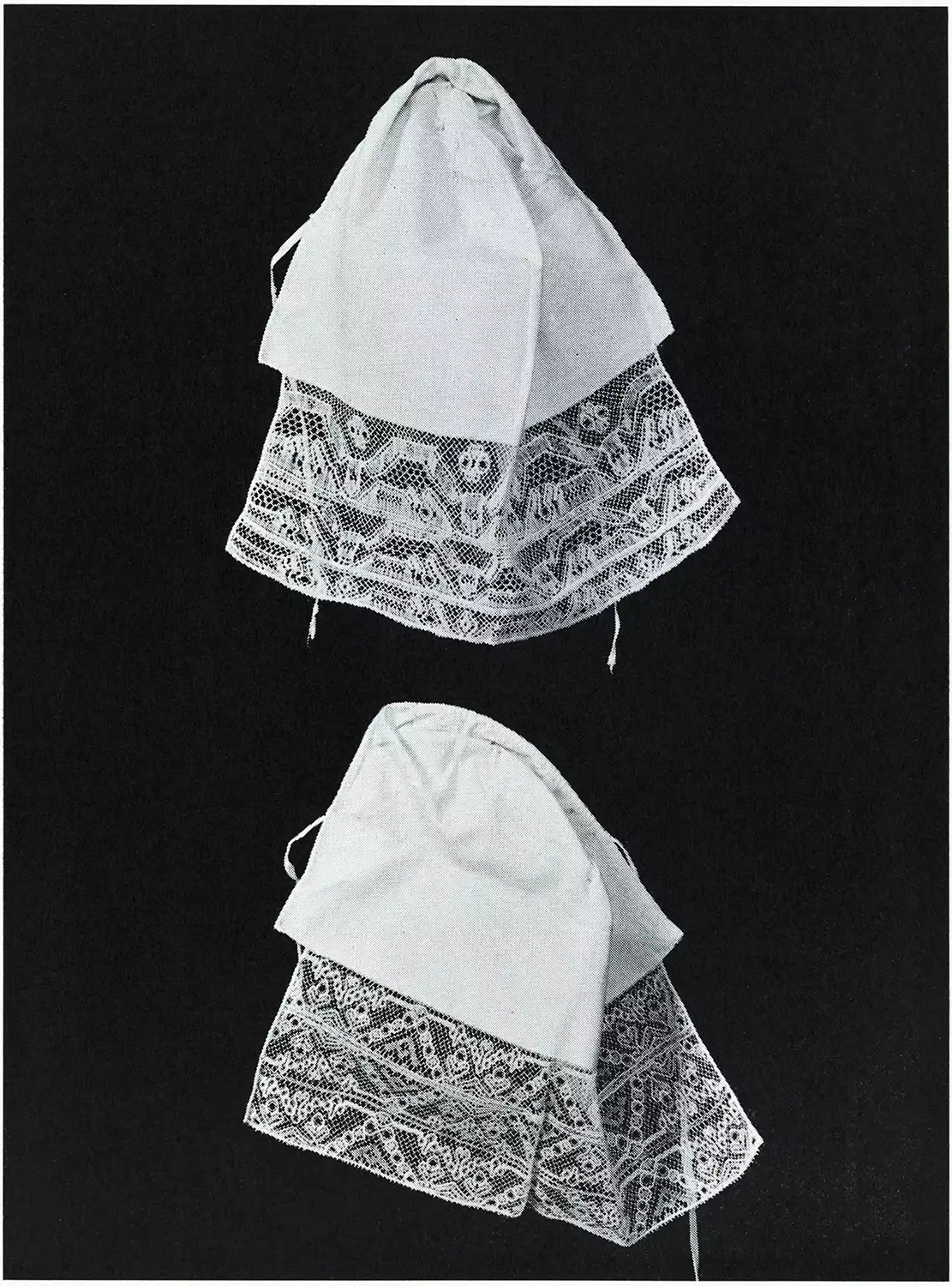

In ornamental weaving the costumes of the women offered the greatest scope for the activity of the peasant artist. It is, however, very difficult at the present day to reconstruct the costume worn in the earliest times, even with the aid of mediaval records. If one may judge from an apparently very ancient usage, which continued down to the middle of the 19th century in the district of Poniewiesh (Government of Kovno), and even now persists among the Letts of Kurland, the Lithuanian women wore long wide robes of wool or linen which enveloped the entire figure, and were fastened at the shoulder by a large round clasp of silvered metal, which was embellished with a relief-like floral ornament.

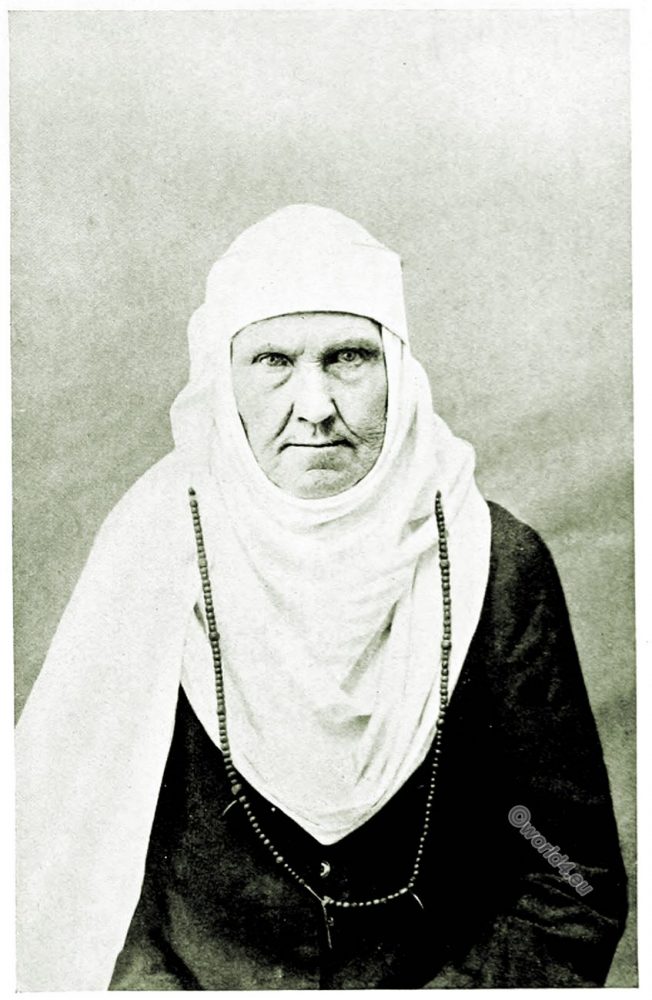

The so-called “namitka” may be regarded as the sole rudimentary survival or this garment. It is still worn by old peasant women in various localities in the Kovno Government (1), and consists of long narrow strips of white linen which are wound round head and neck, the ends hanging loose on the back or shoulders. The Slavic origin of the word “namitka,” and the use of this article of apparel by the peasant women of Volhynia and Podolia until the beginning of the 19th century, seem to confirm the legend which attributes the introduction of this headgear into Lithuania to Jagiello, King of Poland and Prince of Lithuania (2). According to this legend all baptized Lithuanian women received from Jagiello one of these white “namitkas,” to distinguish them from those who remained heathens.

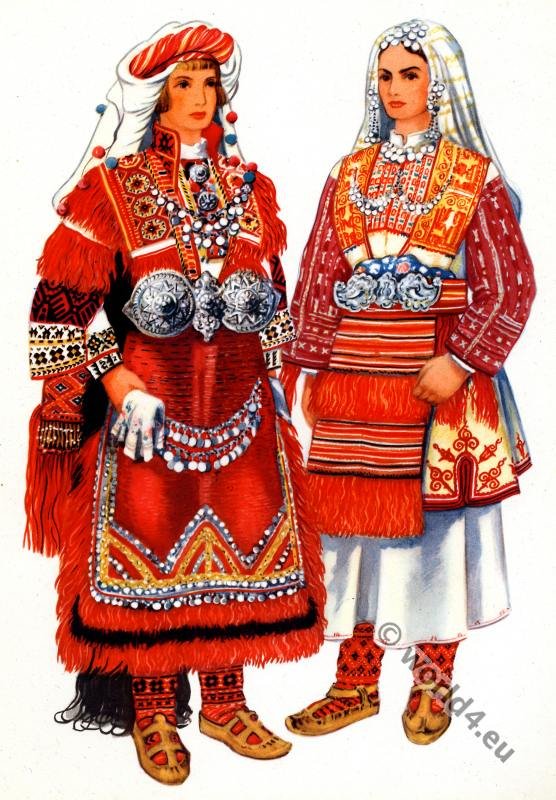

Of particular richness and variety of color was the costume worn in the north of Lithuania-the district of Zmudz. The oldest of the female costumes with which we are familiar at the beginning of the 19th century consisted of the “namitka,” a laced corset, a skirt, a long dark-blue jacket or coat, and an apron with an embroidered lower edge. At a later date the jacket or coat became shorter, reaching to the knees only, and was pleated at the bottom (Nos. 520 and 523), while for headgear a factory-made cloth took the place of the “namitka.” The coat, from the bust downwards more and more closely pleated, became in time to be known in North Lithuania as “ŝimtakvaldis,” i.e. “a hundred pleats.” The corset, made of patterned wool or silk material and often provided with metal fastenings, was characteristically short in North Lithuania, somewhat reminiscent of the taille of the Empire mode, which is still to be met with in Sweden, but not elsewhere in Lithuania.

With the exception of the three silk cloths worn wound round the head, which were of factory origin, the whole of the costume was a product of domestic industry-the “hundred pleated” coat, the pleated corset, the striped skirt woven of wool, the linen apron, as well as the openwork collar of glass beads. Equally original was the bridal dress worn at the same period in North Lithuania, which differed from that worn in other parts of Lithuania, and was made of wholly of factory-made materials. The so-called “crown” formed a distinctive part of this attire, and was made of colored silk ribbons manufactured in Prussia. In the district of Poniewiesh (Kovno) the women until quite a short time ago wore broad bands made of gold thread “kaspininkai” with lace edging and silk lining, which like-wise were of German origin. These bands or galoons were wound round the head and fastened at the back. The only relic of the early costume that remains in North Lithuania is the partiality for crude colors both in the home-woven woolen stuffs and in the fabrics bought from traders. In place of the striped coats that used to be worn, and which closely resembled the work of peasants in the neighborhood of Lowicz in Poland, Scotch checks have now come into use, while the corset and the pleated jacket have gone out altogether. Nor are these few survivals any longer met with ill other parts of Lithuania.

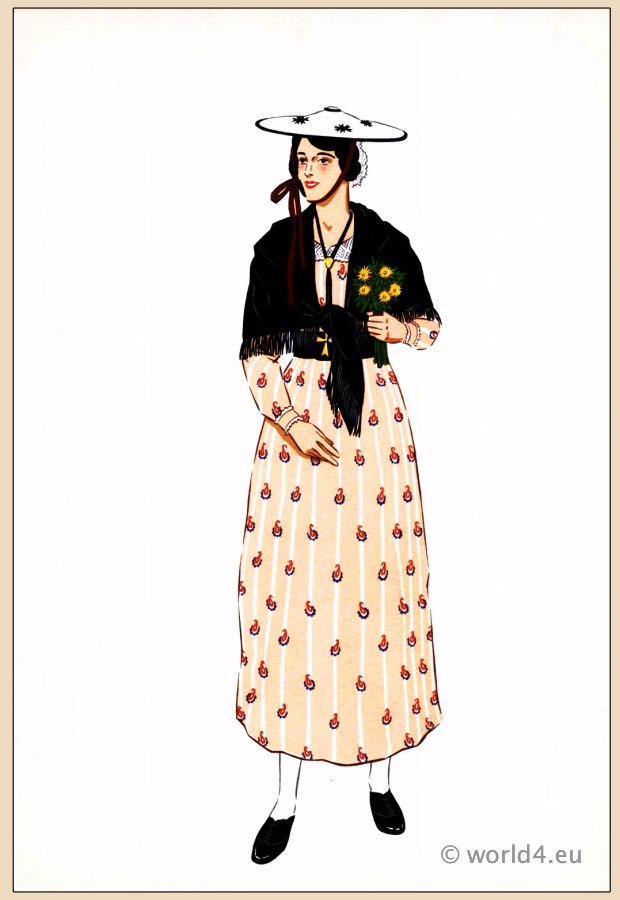

Only in recent days, when the national renaissance has been proceeding with rapid strides, have the Lithuanian women begun to wear a national costume on the occasion of important festivals- a costume borrowed from the province of Suwalki. Owing to the close relations which have subsisted for centuries between the Lithuanian inhabitants of this district and the Polish Mazurs, this costume strongly resembles that worn in the neighborhood of Cracow.

The costume of the men has fared even worse than that of the women, and it fell into disuse before this. From analogy with the costume worn by the Lettish men in Courland and according to information given by aged inhabitants, it consisted of a long home woven woolen coat of a dark-blue or grey color, resembling in cut and fold the above described jacket of the women. At the present time the men wear short coats of grey home-woven cloth, having the cut of a town-made coat. Here and there in North Lithuania the fur cap, at one time generally worn by the men, is still retained under the name of “triausé,” i.e. three-eared-a form which points to its having been adopted from the people of a country with a very severe climate, probably from the Finns, whom the Lithuanians once had for near neighbors, and a branch of whom now settled in Lappland still wear a similar cap. The wooden shoes “klumpie“, still frequently met with in North Lithuania and often bearing carved or painted ornamentation, are akin to those now in use in Sweden. Besides these, shoes made of plaited leather are in general use.

On the southern and eastern boundaries of Lithuania woolen girdles of a kind quite unknown in the north are extensively worn. They are from two to ten centimeters wide and about three meters long, and are ornamented at both ends with fringes; they are handwoven and the patterns are very varied, some showing a close resemblance to the girdles worn in the adjacent parts of White Russia, while others are similar to those found among the Laplanders.

While in the northern districts of Lithuania the home-woven stuffs have only stripes or checks by way of ornament, in the south, i.e. in the Government of Suwalki, ornamental motives derived from the plant world are principally made use of, along with geometrical patterns, as in the aprons and table-cloths; and here the tulip motive “Tulpinis raštas“, wholly unknown in the north and extremely rare in Central Lithuania, is very much in evidence. Curiously enough the only other place where this motive is met with is Bosnia, and there it is treated differently, while its use is unknown amongst Lithuania’s neighbors.

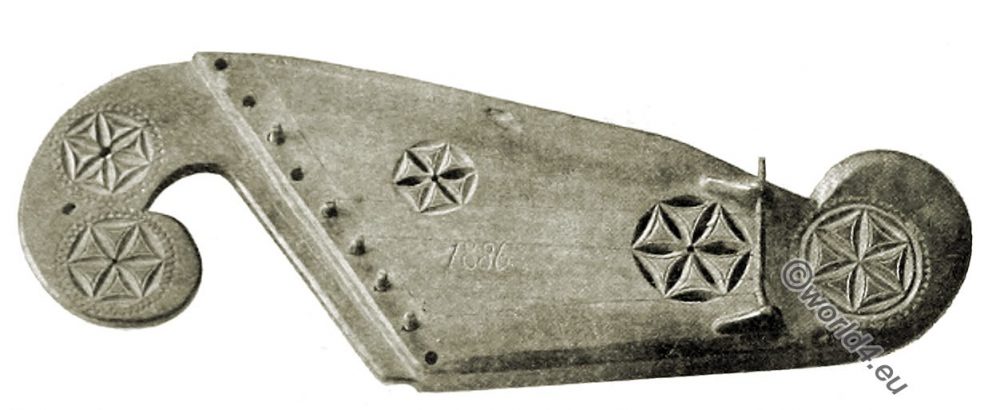

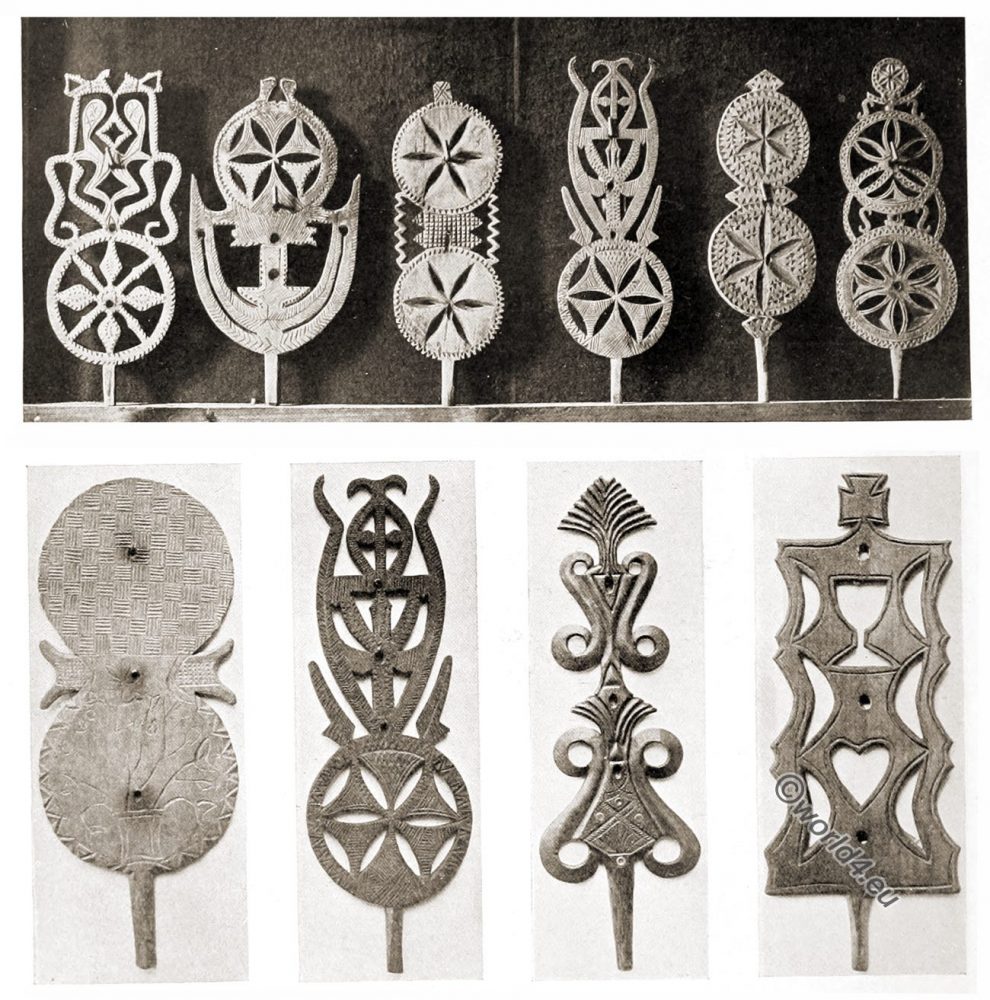

The practice of using carved ornamentation for domestic utensils is very general in the northern districts of Lithuania. A wealth of such ornamental devices is displayed in the boards to which the spindles are attached at the spinning-wheel. This implement is derived from Sweden, where it is in common use and known as “rockblad”; thence has come its form, size and, to a large extent, its ornament.

Very original, and unknown elsewhere in Europe, is the long wooden needle called “šveikele,” used for fastening the wool or flax to the board of the spinning-wheel (No. 538). It is cut out of a single piece of wood, although it often has a few links at the end.

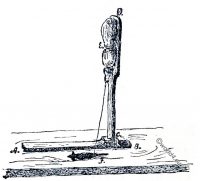

One cannot help marveling at the patience bestowed on the making of these implements; sometimes a lad will spend several days in making a single needle for presentation to his sweetheart with one of the carved boards. Another implement which served the same purpose as these boards was that which is here figured-the so-called “Przaśnica,” an appliance which doubtless originated in very early times before the spinning-wheel existed. The board AB is used as a seat; the flax E is attached at CD, whence the fibres are wound on the spindle F. The board CD usually has carved ornamentation on it, and one example which hails from the government of Kovno, and belongs to the year 1774, bears a striking likeness in motive and technique to similar implements from the district of Lida in the Vilna Government, where the Lithuanians have mingled with the White Russians and borrowed their ornamentation.

Similar decoration is found on the “kultuves,” a kind of stick or beetle used in laundry operations, as well as on the “abrusienicze,” or towel-rails (No. 536), and other articles. These objects are often painted in divers colors.

From their long and intimate relations with the Finns, the Lithuanians derived a stringed instrument, now coming into use again after being long discarded-an old Finnish instrument somewhat akin to the zither, and called in Lithuanian “kanles” (No. 546), a variation of “kantele,” the name by which the instrument is mentioned in the Kalevala.

The favorite colors of the people of North Lithuania, to judge by their preferences in both home-woven and purchased stuffs and the pigments used for their household implements, are red, green, and yellow; in the south, besides these, blue and violet are in vogue, but red is dominant everywhere. A North Lithuanian proverb says, ” What is red is beautiful,”* and up till the middle of the 19th century an entirely red costume was worn there, of which the writer possesses an example. In combining the crude colors regard is always paid to the rules governing the complementary colors; the vegetable dyes in use are prepared at home, and the harmonies of tone achieved with them have resulted naturally from long usage.

- It is the same with the Russians. In Russian krasny means both red and beautiful.

In recent times there has been an active revival of weaving as a domestic industry, especially in the north, thanks to the support given to the movement by the landed proprietors.

It remains for us to mention what are, perhaps, the worthiest products of the artistic activity of the Lithuanians-namely, the carved crosses and “chapels” which they are wont to set up outside their homes, by the roadside, on the summits of hills on the graves of the dead, and in other places as memorials of their gratitude to God or as marks of their sorrow. The country used to be full of them, and they gave it a quite specific character, so that at one time the line of demarcation of the cross-strewn territory practically coincided with the ethnographic boundary of Lithuania. Nowhere else in Europe, with the exception of a part of Hungary, are such richly ornamented crosses erected. It is hardly possible to group them into definite types. In every diocese, and even in every village, the crosses show differences of proportions, form, ornament, color, and iconography. In regard to form, as well as ornament, individual freedom has had full play. The ornamental motives are very varied, and the plant-world has been largely drawn upon. All styles are represented among them, derived probably from the churches in the vicinity. Particularly noteworthy are the iron ornaments which usually crown the roofs or canopies of such” chapel crosses.” Simple as they are, and mostly made by illiterate village smiths, they often possess a certain nobility of line and display a wealth of fantasy.

The carved wooden figures of saints which form part of these memorials naturally follow as closely as possible the recognized iconography of the Church, and differ from similar productions in other countries only in their primitive technique. This branch of Lithuanian peasant art received its death-blow about half a century ago, when an interdict was issued (1864) against the erection of such crosses in other places than cemeteries, and the revocation of the interdict in 1896 has had very little effect in reviving it. The number of “chapel-crosses” is diminishing year by year, and their place is being taken more and more by smooth commonplace wooden crosses which are destitute of decorative features.

We come at length to the following final result of our investigation. The older peasant art of Lithuania, and particularly that of its northern parts, is predominantly akin to the Finnish, and to some extent to the Scandinavian; while, in its later forms, it shows more affinity to Slav types. The neighbourly relations which subsisted for so many years between the Lithuanians and the Finns have given to them a common stock of folk-songs and a whole series of similar phrases. Which of the two races has borrowed from the other, and I how much, cannot at present be determined, for the history of their association has so far been very little investigated, and such linguistic studies as bear upon the question have not got beyond the preliminary stage. Light on this problem will only come when the nomenclature of the various ornamental motives and domestic appliances in Lithuanian and Finnish has been subjected to thorough analysis.

By MICHAEL BRENSZTEJN, 1912.

(1) The Government of Kovno (in Russian Ковенская губерния/Kovenskaya gubernya) was an administrative unit of the Russian Empire. As long as it existed, it was part of the Generalgouvernement of Vilnius.

According to today’s terms, it occupied about the western half of Lithuania, its main part being the landscape Žemaitėjė. In the south it bordered East Prussia and within the Russian Empire on the provinces of Courland and Vilnius as well as the Russian-Polish government of Suwalki.

(2) Jogaila (Belarusian Ягайла; * before 1362; † June 1, 1434 in Gródek) was 1377 Prince of Kiev, reigned as successor of his father Algirdas with his (pagan) name Jogaila as Grand Duke of Lithuania from May 1377 to August 1381 and from August 1382 until 1434. After his baptism and the marriage to Hedwig of Anjou (called Jadwiga) on 18 February 1386 – who had been crowned “King” of Poland since 16 October 1384 – he was named Władysław II. Jagiełło, reigned together with his wife until her death on July 17, 1399 and later until his death.

List of pictures:

517 – Cut Paper Design

518 – Peasant Costume from lower Lithuania.

519 – Linen Head-Dress (Namitka) from Kovno.

521 to 522 – Peasant Costumes from lower Lithuania.

523 – Bands of Coral Beads, from Suwalki.

524 and 525 – Examples of Embroidery.

526 to 535 – Carved Spindels.

536 – Carved wooden Towel-Rail (Abrusienicze).

537 – Carved Spindel.

538 – Carved Spinning-Board and Needle (Sveikele).

539 to 541 Examples of Wood-Carving.

542 to 545 – Crosses from Kovno.

546 – Carved Musical Instrument (Kanles).

547 and 548 Earthenware Jar and Jug.

549 and 550 Carved wooden Box-Lids.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.