Xiamen is also known by the local name Amoy, which is also the name of the local dialect. Today the city is one of the economic centers of the Chinese coastal region. Xiamen has the epithet “Crane City”, because supposedly passing cranes had settled here. The famous islet of Gulangyu (鼓浪屿), which belongs to the municipality of Siming, lies off the island of Xiamen. With the Treaty of Nanjing (1842), which ended the First Opium War, Xiamen became one of the ports open to Britain.

Xiamen has been used by Europeans as a trading port since 1541 and was the main export port for tea in the 19th century. Xiamen was the last base of Zheng Chenggong (called Koxinga) until his retreat to Taiwan before the Qing Dynasty, when he became known as the warlord of the Ming Dynasty and pirate leader.

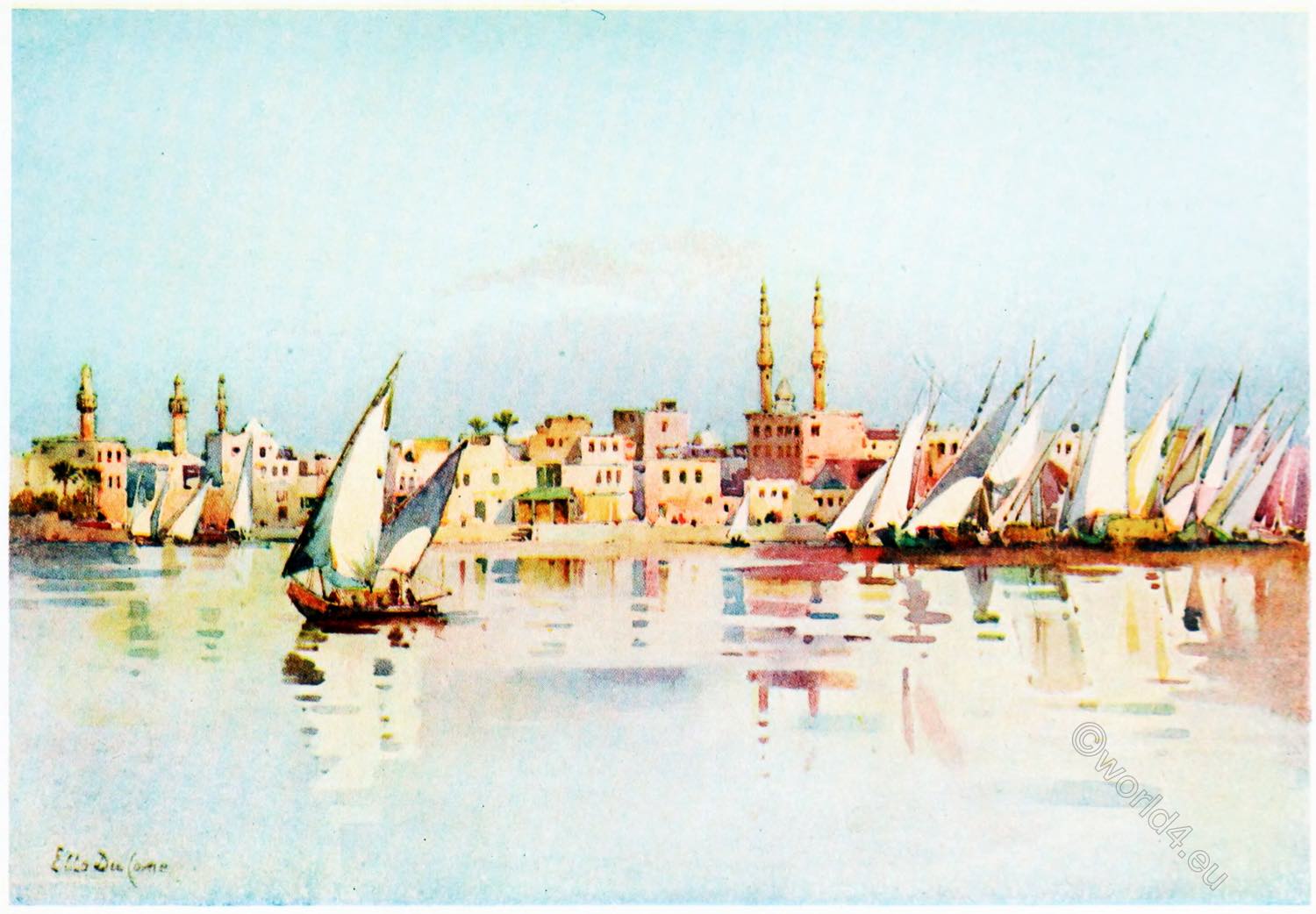

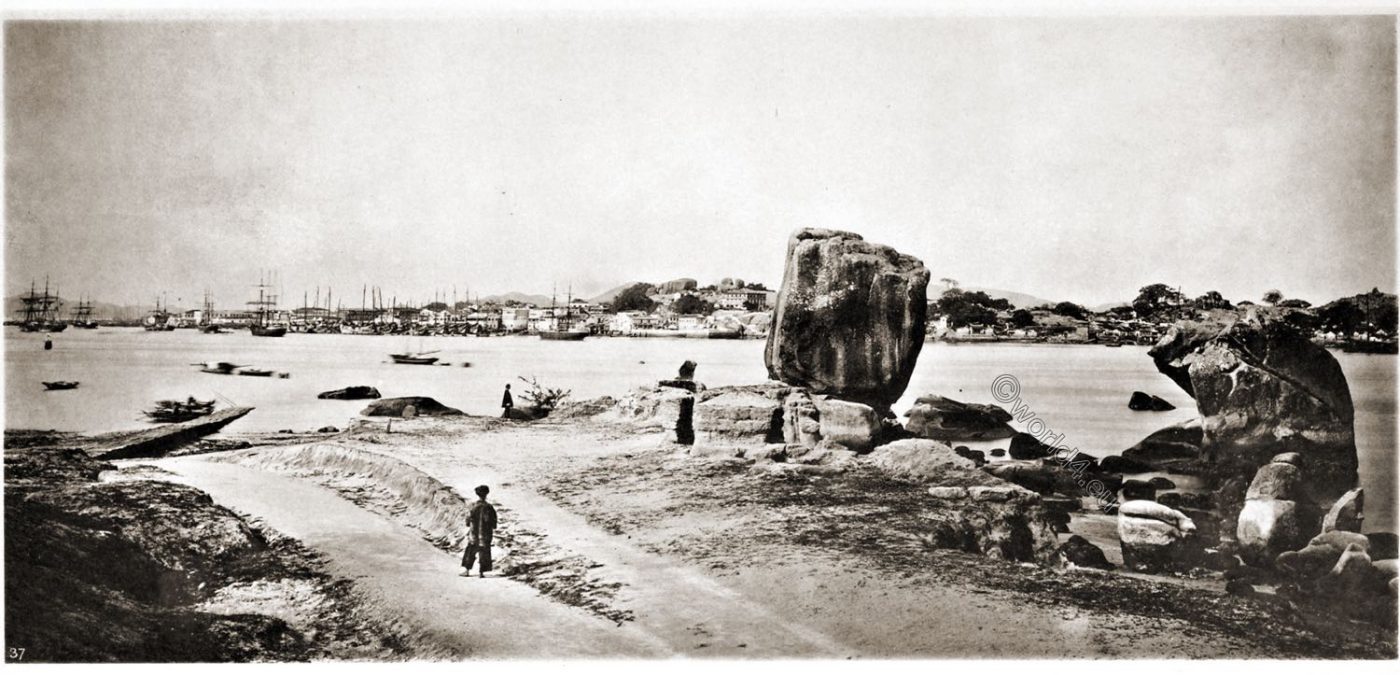

Amoy Harbour.

AMOY (today Xiamen) was one of the earliest ports to which foreigners resorted. About thirty-six miles north of this place is Chin-chew, known to Marco Polo by the name of Taitun, and, about the beginning of the ninth century, the centre of the local export trade. Amoy harbour is one of the finest on the Chinese coast, and at the points from which plate NO.37 was taken, is more than 800 yards across, thus it offers abundance of anchorage-ground for vessels even of the largest size.

There is a maximum difference between high and low water mark here of about eighteen feet. The action of the tide has corroded the basis of many of the bold rocks inside the harbour basin, and a notable instance of this is to be seen in the upright mass of granite which stands in the foreground of this picture, and which is known by Europeans as “Six-mile Rock,” and by the Chinese as the “Sail Windlass Rock.”

To this pinnacle of stone, popular superstition is attached, for the natives look upon it as a kind of guardian genius who has control over the fates of Amoy. When this rock falls (say the credulous) Amoy will fall too. So year by year additional props are planted beneath its gradually diminishing base. In 1544 the Portuguese attempted to establish a settlement on this part of the coast, but the authorities there, more fortunate than they have been since in Macao, made the place too hot to hold the intruders.

In 1624 a second attempt to tap the commercial resources of the district was commenced by the Dutch, who endeavored to establish themselves on Fisher’s Island. This position they afterwards exchanged for Formosa (Taiwan), and from the latter they were finally driven in Koksinga’s time. Amoy was thrown open to foreign trade by the treaty of Nanking. The chief exports from this part of Fukien are sugar and tea, a great part of the latter article being grown in the north of Formosa. The import trade is now very much in the hands of the Chinese merchants, who avail themselves of the coast steamers to run to Hongkong to buy their wares, and who, if persons of respectability and standing, find every facility afforded to them by the banks in carrying on their commercial undertakings, however small their own capital may be.

The irregular, illegal system of inland transit dues is very damaging to foreign trade, and effectually excludes European wares from many of the marts of the interior. Goods on being transported inland, although they have paid the legitimate port dues, are subject to a system of irregular taxation or squeezing, the amounts which are levied fluctuating with the need of the local officials at different points along the route.

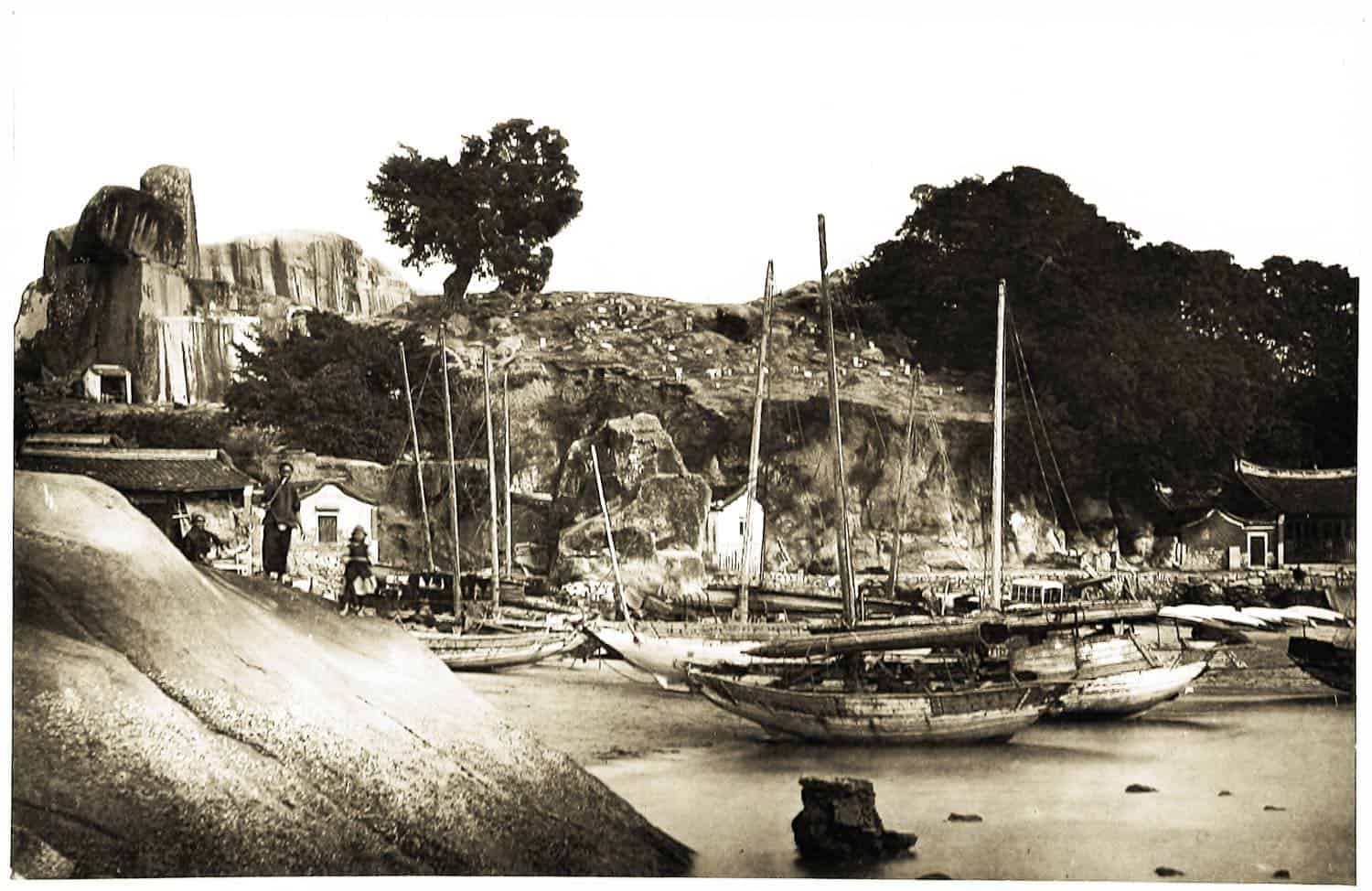

During the war, a tax called le-kin was also imposed to meet the military expenditure. This tax is still levied on foreign merchandize at Amoy, while Swatow and the other ports on the coast, except Formosa, are none of them similarly burdened. Part of the carrying trade from this port to Formosa, Singapore and Batavia is still done in junks, for these, as I believe, are less heavily taxed than square-rigged ships.

The photograph shows that part of the native town of Amoy where the offices of foreign merchants have been built, the town itself stands on the west of the island from which it takes its name.

The harbor of Amoy (Xiamen). Fujian Province China. (Treasure spots of the world)

AMOY HARBOUR, CHINA.

THE little island of Amoy nestles close to the coast at the southern extremity of the Fujian Province of the Chinese empire. The native name of the island is “Hia-mun,” and it forms one of a group of many such islets that stud the coast of Fujian.

Historically, this part of the province has a deep interest attached to it, in so far, at least, as European intercourse is concerned. If not the earliest, it was one of the first ports resorted to by European traders- a fact which may be gathered by an inspection of the ancient foreign gravestones bearing Latin inscriptions that are still to be found on the hills of Amoy, Kulangsu, and the adjacent islands. It was here, too, that Koksinga, the celebrated Chinese sea-king, is reported to have assembled his fleet, with which he crossed to Formosa, and in 1661 succeeded in expelling the Dutch from that island. The hardy islanders of Amoy, after the conquest of China by the Manchus, or Tartars, were the last to succumb to the foreign yoke, and, indeed, even to this day the Amoy men wear a dark turban to conceal the badge of disgrace, the tonsure and queue imposed upon the Chinese by their Manchu conquerors.

The harbor of Amoy is one of the safest and most accessible to be found along the coast of China, nor does its position lack picturesqueness, as it is guarded by an array of bold granite rocks, upon which the natives look with awe and reverence, while the hills around present a multitude of gigantic granite boulders, wearing the most grotesque shapes, and perched in strange disorder on their summits. These have been gradually left bare and exposed by the silent power of disintegration, which has been going on for ages. These rocks, many of them, are now shaded by the graceful bamboo or the wide-spreading branches of the banyan, while temples and shrines have been reared beneath them, and consecrated to the local guardians of the Buddhist faith.

One of the strangest and, to the traveller, most unaccountable objects to be encountered on those granite rocks, are rows of earthenware jars filled with human remains, and each one carefully labelled. These are the bodies of the poor, which are set there by their mourning relatives to await happier times, when the needy survivors, by some unexpected turn of fortune, shall be enabled to purchase for their beloved kinsmen the sacred mortuary rites, and consign their bodies to some peaceful resting-place.

Descriptive Article by J. Thomson. Photographed by Thomson.

Source:

- Illustrations of China and its people: a series of two hundred photographs, with letterpress descriptive of the places and people represented by John Thomson. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle 1873.

- Through China with a camera by John Thomson. London; New York: Harper, 1899.

- Treasure spots of the world: a selection of the chief beauties and wonders of nature and art by Walter Bentley Woodbury (1834-1885); Francis Clement Naish. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler, Paternoster Row, 1875.

Continuing

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.