Buddhist monks toll bells 108 times daily in monasteries, a ritual symbolizing the complete Chinese year and offering solace to souls. This number encompasses the year’s months, solar terms, and 5-day periods. While tolling methods vary regionally, the shared belief is that the bells’ sounds provide relief for those in Buddhist hell. Chinese writers, however, dispute this, claiming bell tolling serves as musical or signaling functions, not for saving souls from the afterlife.

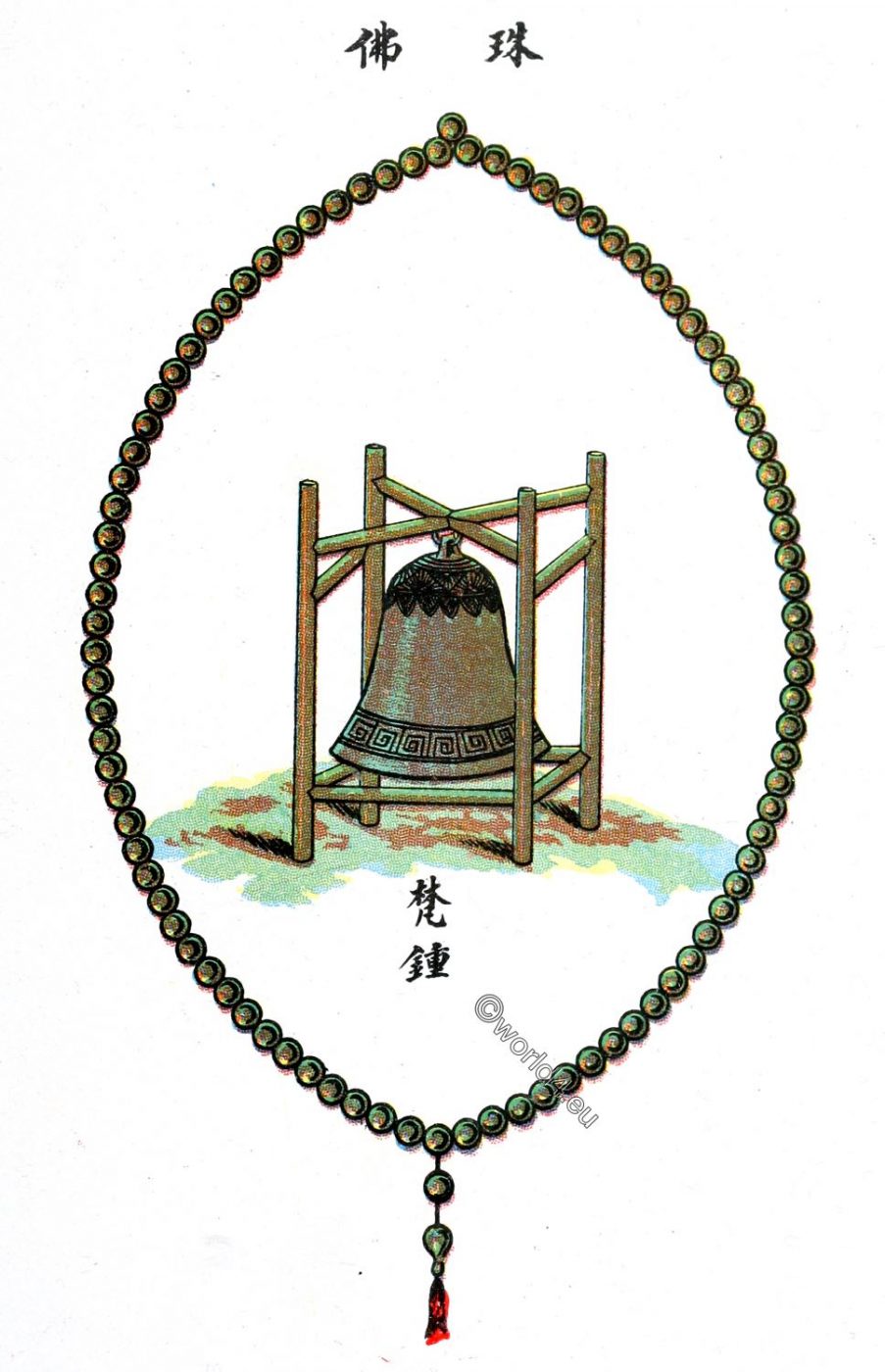

Tolling of Buddhist Bells. Chwang-fan-chung.

In almost all Buddhist monasteries, may be seen a bell, which is tolled by the monks morning and evening. These regular tollings comprise a series of 108 strokes. This number 108 represents:

1°. The twelve months of the year= 12.

2°. The twenty-four divisions of the Chinese year, corresponding to the different positions which the sun occupies with reference to the 12 signs of the zodiac. These 24 terms, or tsieh divide the solar year into 24 periods of almost equal duration. They are the following: Slight cold, Great cold, Beginning of Spring. Bain water, Excited insects, Vernal equinox, Pure brightness, Corn rain, Beginning of Summer, Small fulness (grain fills), Sprouting seeds (grain in ear), Summer solstice, Slight heat, Great heat, Beginning of Autumn, Stopping of heat, White dew, Autumnal equinox, Cold dew, Frost’s descent, Beginning of Winter, Slight snow, Heavy snow. Winter solstice = 24.

3°. The 72 divisions of the Chinese year into terms of 5 days. Each of these terms of five days is denominated “Hen”. Now, the number 72 X 5 gives the Chinese year of 360 days.

Adding up the months, the twenty-four terms or tsieh and the periods of five days or “heu” in a year, we have the total of 12 + 24 + 72 = 108. It is the whole year which is thus entirely devoted to the honor of Buddha.

The manner of ringing these 108 strokes varies according to different places. The following are a few selections.

1°. At Hang-chow, Capital of Chekiang province, the tolling is regulated by the following quartet, which has become a popular tune.

At the beginning, strike thirty-six strokes:

At the end, still thirty-six again;

Hurry on with the thirty-six in the middle:

You have in all but one hundred and eight, then stop.

36 + 36 4-36 = 108.

2°. At Shao-hsing another quartet has the following:

Lively toll eighteen strokes;

Slowly the eighteen following;

Repeat this series three times,

And one hundred and eight you will reach.

(18 + 18) X 3 = 108.

3°. At T’ai-chow another city in Chekiang province, we find the following ditty:

At the beginning, strike seven strokes;

Let eight others follow these;

Slowly toll eighteen in the middle;

Add three more thereto;

Repeat this series thrice;

The total will be one hundred and eight.

(7 + 8 + 18 + 3) X 3 = 108.

Why these bells are tolled.— Although the manner of ringing differs according to different places, it is fancied everywhere, that the sound of the bell procures relief and solace to the souls tormented in the Buddhist hell. It is thought that the undulatory vibrations, caused by the ringing of the bells, provoke to madness the king of the demons, T’oh-wang render him unconscious, blunt the sharp-edged blades of the torturing tread-mill, and also damp the ardor of the devouring flames of Hades.

At the death of the first Empress Ma of the Ming dynasty, every Buddhist monastery tolled thirty thousand strokes for the relief of her soul, because according to the Buddhist doctrine, the departed on hearing the ringing of a bell revive. It is for this reason that the tolling must be performed slowly. 1)

1) See: Liang-pan ts’iu-yu-hoh, Shi wen lei tsü, Leng-kia king, Yung chw’ang siao p’in.

Chinese writers refute these Buddhist notions about bells.

We read in the Lü-shi ch’un-is’iu that the Emperor Hwang-li ordered Ling-lun to cast twelve

bells, in order to fix the musical notes. The work known as Yoh-ki (Memorial of Music), says: “the tolling of bells is used as a signal”.

According to these two writers, such is the precise purpose for which bells are used. They either give forth musical notes, or they are rung to give signals (of joy, sadness or alarm …), but there was never any idea of employing them to rescue the dead. The work entitled “Shi-ming” Buddhist names, has the following: “the bell is a hollow instrument; the larger it is, the deeper are its sounds, but who could cast one large enough to make its tollings heard in the infernal regions? Even should that happen, such a sound is but a mere empty noise, incapable of awing the ruler of Hades, and powerless also to break the sharp-edged tread-mill which tortures the damned. Wealthy families, desirous of rescuing from hell the souls of their ancestors, offer presents to the Buddhist monasteries, in order that the monks would toll the bells unceasingly day and night, and perform this service even for several successive days.

They may toll them till they deafen the ears of the neighbors, who curse and swear at them: they may ring till the bells burst, they will never thereby rescue a single soul out of Hades. It matters little whether they toll a brass bell or strike on a wooden one, the result is practically useless in both cases”.

Source:

- Recherches sur les superstitions en Chine par Henri Doré. Le Panthéon Chinois, Zi-Ka-Wei 1916.

- Illustrations of China and its people: a series of two hundred photographs, with letterpress descriptive of the places and people represented by John Thomson. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle 1873.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.