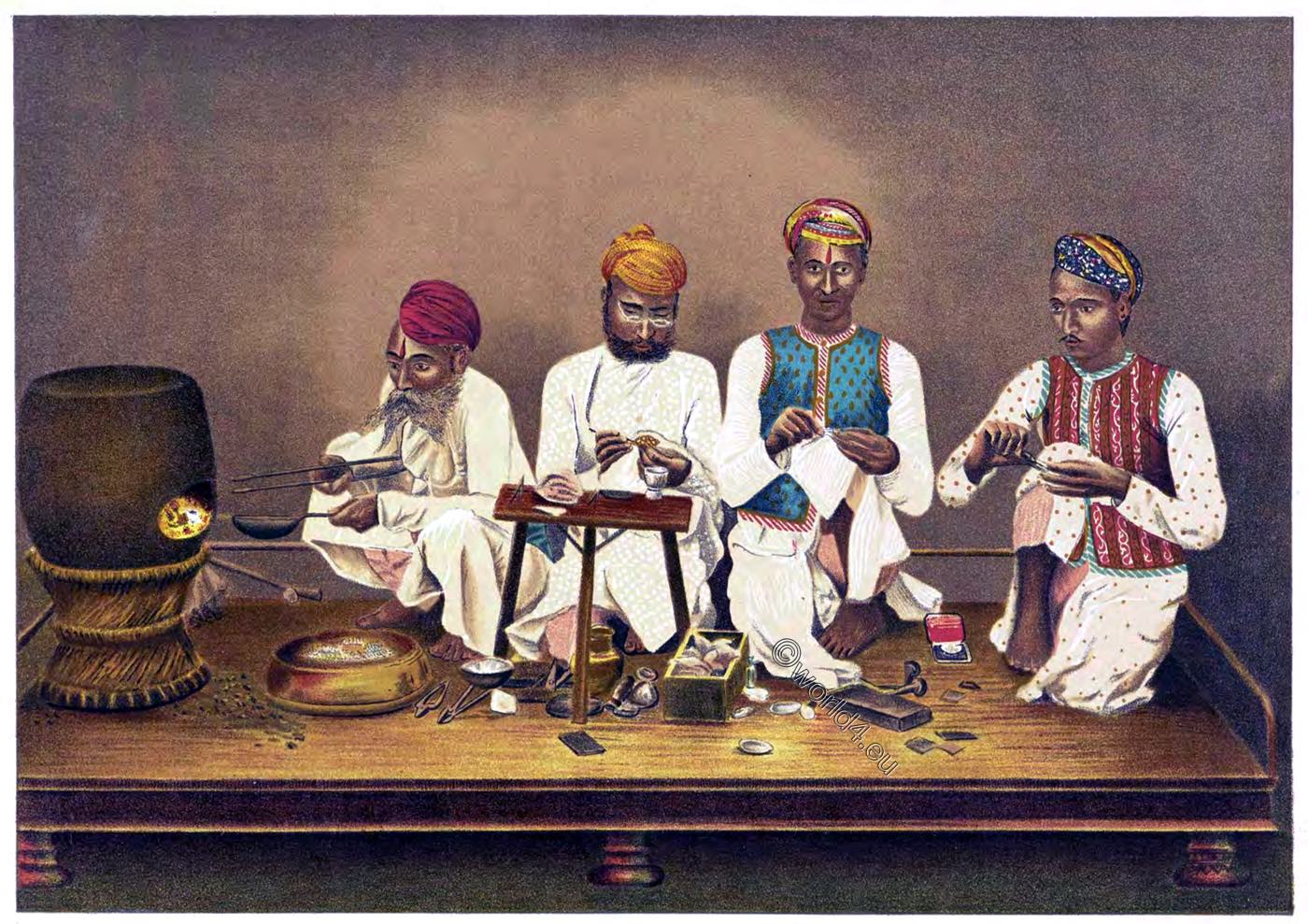

Group of Jaipur Enamelers at work.

(From “Jaipur Enamels,” by S. S Jacob and T. H. Hendley 1886.)

In 1886 I wrote (Author T. H. Hendley) the text to accompany a series of enamel designs, which were drawn by one of the best Jaipur artists, Rani Bux, son of Esar, for Lieut.-Col. (now Colonel Sir Swinton S.) Jacob, K.C.I.E. The following description of the plate, which has been copied, is taken from that work, which was published by Mr. Griggs Group of Jaipur Enamellers at Work. The principal enameller in this group, Guma Singh, son of Kishan Singh, sits before a low stool upon which his colours and styles are arranged. The larger implements are placed on the ground near him, and he holds the piece on which he is at work in his hands.

The colours are placed in depressions in a thin brass plate which is wedged into the front of the stool. On his right, Dhuna Singh is engaged in heating the enamelled plate in a small clay furnace; Behari Singh, who sits on his left, polishes an ornament after the colour is fixed, and Hazari Singh is engraving another plate.” All the men are Sikhs, descended, it is said, from five enamellers who were brought from Lahore by Maharaja Man Singh, the friend of the Emperor Akbar.

The art of enamelling.

Enameling may be described as the art of colouring and ornamenting the surface of metal by fusing over it various mineral substances. Success depends on the skill and resources of the operator and the materials employed. The range of colors attainable on gold is much greater than on silver and still more so than on copper or brass. This peculiarity is to a certain extent overcome by silvering or gilding the surfaces intended to be enameled.

Various Forms.

There are known to exist three or four forms of enameling, such as the cloisonné of Japan and China, in which wires are fastened by a gum or simply impinged or in others welded to the surface of the metal, in elaboration of the design, much as in some forms of filigree. The various spaces thus outlined are next loaded with the coloring materials, and the article placed in the furnace until the glasses fuse, when the purpose of the wires becomes apparent, namely, to save the various colors from being intermixed and the design thereby hopelessly destroyed.

The second form is known as champlevé in which the metal is engraved or chased, repoussé or blocked out in such a way as to provide depressions within which the colors can be imbedded.

Chief Centers.

In Jaipur, Kach, Bhawalpur, Delhi, Lucknow, Benares and Rampur and other towns of India the pattern is chased, in Kashmir reposed, and in Multan it is blocked out by means of dies.

But in India the resources of the jeweler are limited, though his results are often extremely beautiful. His furnace is very small and his methods of heating defective, hence comparatively small articles only can be enameled, the colors being applied time after time, those that can stand the greatest amount of heat being first used and the others in order of their fusibility.

A third mode and that which prevails for the most part in Kashmir is to paint the surface with a sort of silicated or readily fusible paint and then to subject the article to a moderate heat, sufficient to melt the paint but not to cause the colors tu fuse together.

Materials used.

The flux used is invariably borax, tin oxide being added to lower the required temperature but with the further result of making the glass or enamel opaque. The colours are silicates and borates of the metals, the chief being a yellow produced through the use of chromate of potash; violets through carbonate of manganese; blues through cobalt oxide; greens through copper oxide; browns through red iron oxide; blacks through cobalt copper, manganese and red iron oxides being used along with a glass composed of 100 parts of quartz, 50 borax and 200 red lead.

The brilliant reds attained by the Jaipur, Delhi and Benares workers on gold are the most difficult of all colours to produce, and their secret is therefore more or less rigorously preserved. White or ivory colour is also difficult, but is obtained from antimoniate of potash, hydrated iron oxide and carbonate of zinc, added to the ordinary glass.

Sources:

- Indian art at Delhi, 1903: being the offical catalogue of the Delhi exhibition, 1902-1903 by Indian Art Exhibition. Delhi; Sir George Watt. Calcutta: Superintendent of Govt. Print. 1903.

- Indian jewelry by Thomas Holbein Hendley. Journal of Indian Art 1909.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.