HOW GREEK WOMEN DRESSED BY PROFESSOR G. BALDWIN BROWN.

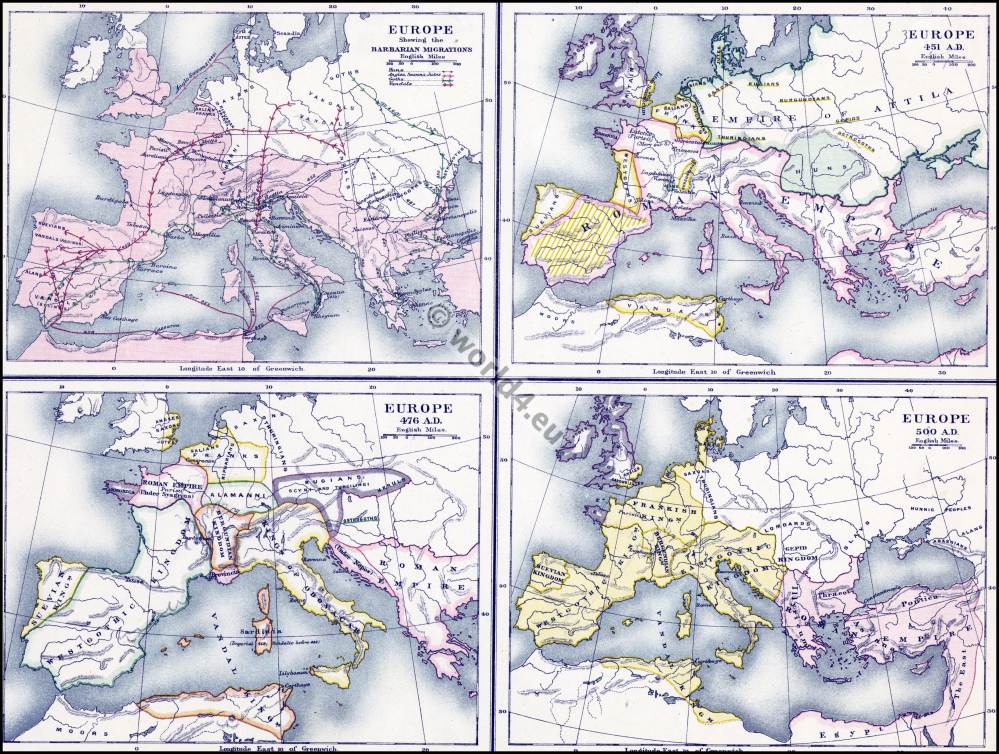

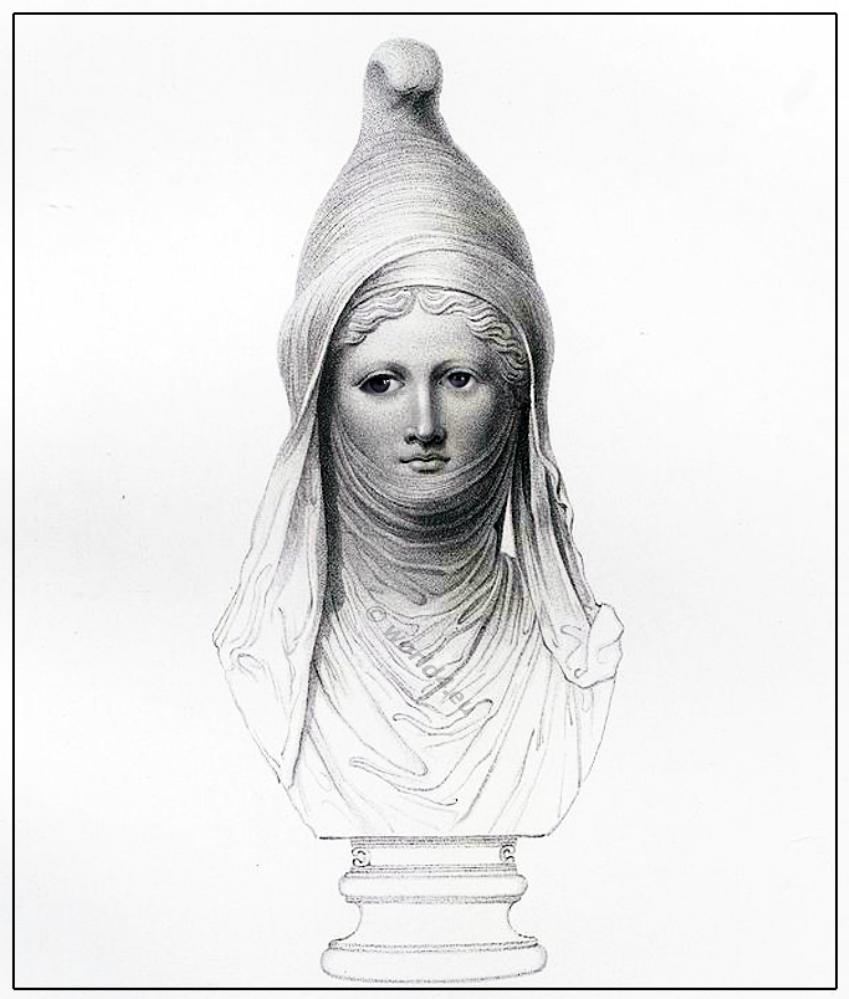

IN the present and in a succeeding article it is proposed to deal with some points of artistic interest connected with the Greek female dress of the classical period. There was no difference in principle between Greek male dress and that of the women. In the case of the latter some minor additions, such as veils, were sometimes worn, but essentially the female dress, like the male, consisted in two garments, either or both of which could form the costume, and which correspond roughly to tunic and mantle.

It is recognized that in many cases both the upper and the under garment were plain rectangular pieces of stuff folded round the body, and held in their place either by the nature of the cast, or by temporary fastenings, and it is the argument of these articles that this is true of the normal Greek costume, not only in many cases, but in all; so that, if we put aside certain rare and exceptional appearances, all the forms of Greek dress found on the monuments can be produced without the aid either of scissors or of needle and thread.

The mantle varied in size, and was worn in many different fashions, enveloping the whole or only part of the person, and sometimes merely draped, but at other times fastened with a brooch of some kind like a Scottish plaid. In one form of it, that of the chlamys, a military cloak affected especially by youths, it was quite small, and was clasped on the shoulder or at the neck. The ampler mantle worn by older men and by ladies, and often called himation, was large enough completely to envelop the person. It was generally worn without brooch. Illustrations of the methods of its use, some of which present difficulties, will he given in the succeeding article.

The tunic must not be regarded as merely an undergarment, like a modern shirt or shift. It was intended in itself to serve all the purposes of dress, save where special protection of the person was desired. It could be coloured and artistically adorned, had showy fastenings, and was completed and rendered serviceable by a girdle. It corresponded to the Latin tunica, and the English form of this word is the most suitable term by which to denote it.

The monuments show us tunics of two distinct kinds. One is evidently of thicker stuff than the other and falls into larger folds. It is worn shorter and without sleeves, or without any part of it covering the arms, and is sometimes open on one side. The other falls into multitudinous crinkly folds, as would be the case with a thin fabric of ample dimensions. It descends below the feet and generally covers the arm, or at any rate the upper part of it, with a full sleeve. A girdle is, or may be, worn with either dress, and in addition the latter kind is sometimes confined over the bust and under the arms by secondary bands. The one seems to be woolen, the other is evidently of a fine linen or cotton fabric, and they appear generally to answer to the traditional distinct ion which archaeologists have drawn between the Doric and the Ionian tunics.

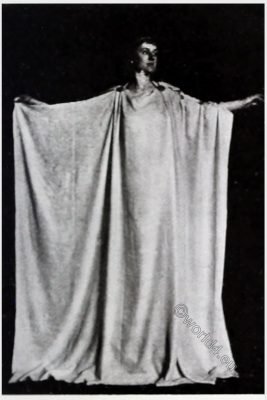

It is customary among scholars who have given attention to this subject to assume that, while the Dorian tunic was merely draped round the figure, the Ionic garment was shaped and sewn. This is interred partly from its fully developed sleeve, which it is supposed could nut he made without the scissors, and partly from a certain passage in Herodotus, on which has been based the theory that any vestment fastened without the use of long pointed pins must be closed by the needle and thread. Experiments, however, made with actual drapery upon a model or a lay figure, show that the fully developed sleeve, even reaching to the wrist, can be perfectly well formed by the proper manipulation of a rectangular piece of stuff, while there are several ways of fastening a dress that do not involve the use of long pointed pins. In No. 1, Plate I, for example, the model is draped in a rectangular piece of fine lawn, measuring about 5 yards by 2, and this is arranged on the model’s left hand in the Doric fashion, on her right in that which would be termed Ionian.

On the one side we see the sleeveless Dorian tunic reaching only to the feet, with the reduplication over the chest, and the arched line of the “fall-over of the dress”, where it is pulled up through the girdle. It is open at the side, so that the wearer shewing the thigh. On the other side, beyond the garland which masks the change in the cast, the robe is draped Ionian fashion, with the superfluity of length, applied to the Ionians in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo. To allow of this ‘trailing on the ground,’ the robe, though girdled, is not drawn up through the zone. Along the arm it is draped in a full sleeve to the wrist.

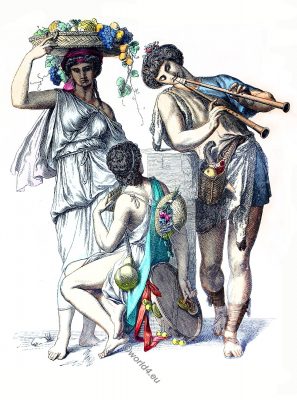

No. 2, Plate I, shows the two fashions in two distinct dresses worn at the same time, and each made from a rectangular piece of stuff. We see here, too, side by side the most ample and the scantiest female costumes found on the monuments. The principal figure, suggested by one on the sculptured drum from Ephesus in the British Museum, is draped in two tunics, a ‘Doric’ one worn over the thinner but more ample ‘Ionic,’ and a himation is furthermore being attached to her shoulders by her handmaid, who is herself attired in the costume of the girl runner in the Vatican, with a small rectangular piece of stuff tied by two corners on the left shoulder and open at the side. The method by which the draperies on the principal figure are produced will be understood from the series of studies which follow, and it will be seen from these that, whatever be the fashion of wearing the dress, it is in all essentials one and the same, and it may be added is always characteristically and charmingly Greek.

The Greek dress is indeed one of the typical products of the Hellenic genius. It exemplifies better than almost anything else the capacity of this gifted people for producing the most beautiful effects by the simplest means. The stuff itself was simple and cheap, and in many cases was the product of the household loom, at which, like Penelope of old, the lady of the house sat at work amidst her handmaids. It might be dyed, especially when it was of wool, any desired color, and be decked with a figured border woven into (not embroidered on) the fabric, but it was not brocaded or patterned all over, and still less made stiff and heavy with gold. Just as the exquisite Greek jewelry depended for its effect solely on the artistic manipulation of thin plates of gold, and was careless of the pomp of gems, so the evenly woven soft homogeneous web of fine wool or flax was taught to fall with a lovely play of lines, and with contrast of broadly-treated with detailed passages, intrinsically beautiful and at the same time nicely adjusted to the artistic purpose of assisting the expression of the form beneath.

It is, moreover, one of the most valuable results of the experimental study of Greek dress that it brings out into the clearest light the truth to nature of the monuments. This applies more particularly to the finest of these, such as the female figures from the pediments of the Parthenon. There is, indeed, a curious realism here in the rendering of the character and details of dress. As is the case with the anatomy of the nude figures, there is evidence in the draped ones of that fresh outlook on nature, that alacrity in seizing on every little unexpected accident, which characterizes the modern artist. The same thing is to be observed in the paintings by Michelangelo on the vault of the Sistine, the only existing works in figure design comparable with the Parthenon pediments. In both the sublime idealism of the creations as a whole is tempered with a quite modern actuality in the details, which gives vigor and life to the artistic effect.

In one of those flashes of real aesthetic insight, which, putting Lucian aside, are so rare in ancient literature, Plutarch writes of the eternal youth that blooms on all the art of the Periclean Age (480–404 BC). This freshness of effect is partly due to a naturalism in details that never descends to prosaic realism, and the curious variety observable in the forms and methods of arrangement of the dresses, with their girdles and bands, is a case in point. For by manipulation of these the robe could be left loosely streaming or girded close, and its length could be adjusted to the taste or occupations of the wearer. It might leave the arms entirely free, or drape them to the wrist, and all these modifications were produced by merely fastening or unclasping a brooch, or tying or unloosening a band. It should also be noted at the same time that this simplicity was not anything obvious or banal. On the contrary, there are appearances which have proved formidable stumbling blocks to scholars, and which cannot be explained merely by the light of nature or from Pollux. Actual experiment will generally reveal the secret, and when we see how it is done – but not till then – it appears self-evident.

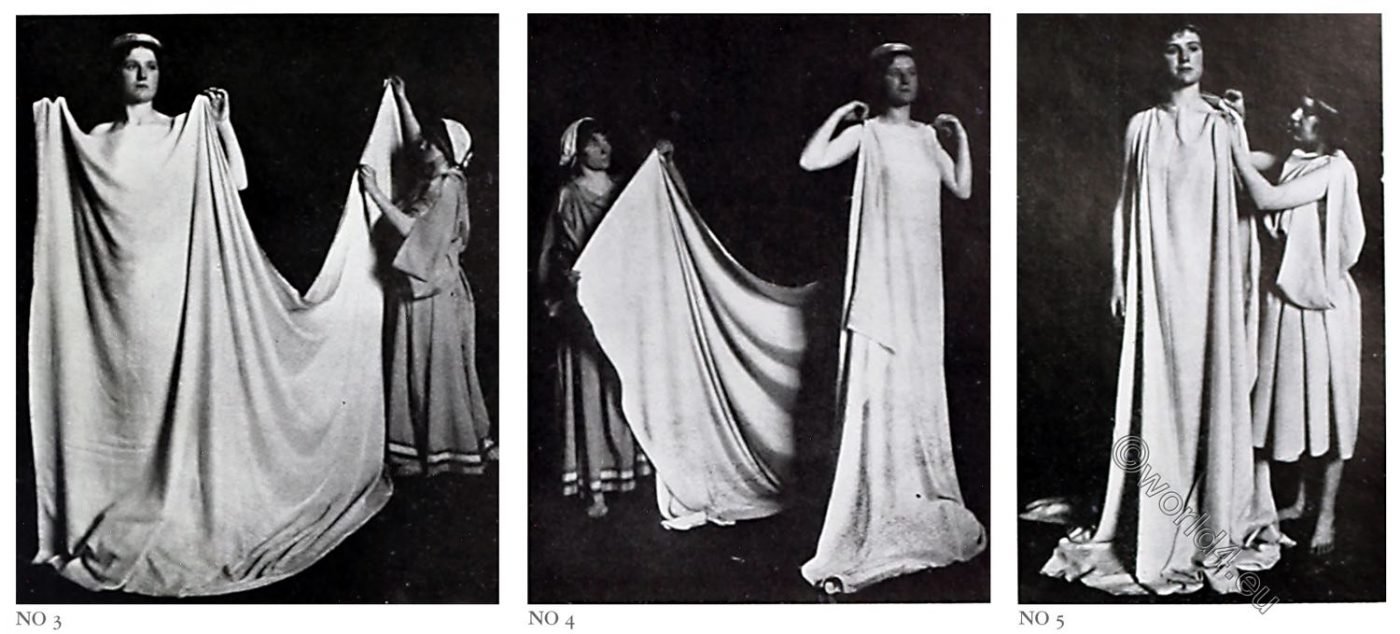

The size and shape of the piece of stuff required to form an average Greek female tunic are approximately those of an Indian Chuddar shawl that will measure some 4 yards by 2, while the texture of such a shawl, of fine woolen fabric, renders it very suitable for the purpose. The lady who is to be robed by the aid of her attendant (No.3, Plate II) holds the piece of stuff about 30 inches from the end, while the handmaid, grasping it at the same distance from the other extremity, will bring it round at the back as in No.4, and will attach it on the lady’s right shoulder, where her hand is holding the front portion of the stuff.

A corresponding attachment is then made on the other shoulder (No.5), and the dress, as regards its essential purpose of covering and protecting the body, is already complete. In the matter of these attachments, however, certain details of importance have to be attended to. Wherever two portions of the stuff are brought together, there must be a certain fullness produced by a box-pleat or by gathers, and on this depends a good part of the richness in the folds of the resultant costume. In the case of the plain sleeveless tunic, like that worn by the two ladies in the archaic relief from Pharsalus in the Louvre (picture above) the gathering of the stuff together at the points of attachment is very marked, and the richness thus produced at the sides contrasts effectively with the plainer fall over the front of the figure.

In practice it will be found that 7 or 8 inches of the material must be gathered in in this way, and a box-pleat, though not, perhaps, exactly classical, gives very readily the required effect. The same is the case with the attachments on the arm, which drape the stuff into the form of a sleeve. In archaic sculpture the gathering in of the fabric at each point is indicated by three or four converging wavy lines; but in advanced work, such as the reclining Fate trom the Parthenon, the thin linen web is drawn together in a fan-like arrangement of delicately carved crinkly folds.

A Greek dress fastened without attention to this detail will never show the needful richness. The nature of the fastenings themselves will be considered in the subsequent article.

Another simple precaution that must be taken results in one of the most charming features of the dress. It will be noticed in almost all draped female figures of mature Greek sculpture that the top of the dress in front over the bosom is not straight, but a little full. Lady Evans, in her book entitled ‘Greek Dress,’ remarks on the feature: ‘At the finest period a pleated fold occurs in the front of the neck . . . but how this was produced is not very clear. It may have been secured by pinning.’

As a fact the pretty detail produces itself in the most natural manner possible as a consequence of the simple device of allowing a little more stuff between the shoulder fastenings in front than at the back. This little overplus of 2 or 3 inches makes the stuff wave and fall over upon the bosom in dainty ripples, of which the Greek artist took the fullest advantage.

The dress as now draped on the figure is still open at one side, and it is also far too long for use. No. 6 shows the wearer, mounted for the purpose on a stool, holding out the dress on both sides, so that the full width of it is visible. Attention should for the moment be confined to the side where the fingers hold the corners of the drapery, and the other side must be assumed to correspond. Let us suppose now the dress to be let fall from both hands as shown in No. 7, where a girdle is also seen passed round the waist.

Since in No. 6 the distance between the point of attachment on the wearer’s right shoulder and the bottom corner of the drapery on the ground to the left of the illustration is greater than the direct vertical distance from the shoulder to the floor, it follows that when loosed from the hand the stuff will fall, as in No. 7 lower at the sides than in the middle, and the bottom line of the robe, as the wearer stands on the stool, takes the form of an arch. Now to bring the dress into a serviceable shape for wear it must be shortened, and with this intent it is drawn up through the girdle and suffered to fall over in a kind of roll.

It is obvious that in order to secure a level line at the ultimate bottom of the robe, it must be pulled up more at the sides than in the front, and as a consequence will hang over to a greater depth. This results in that arched line over the hips which reproduces the line at the bottom of the freely hanging robe in No. 7. and is familiar on the monuments, as in the case of the Vatican Caryatid given in No. 8. The appearance of this arch over the hips has proved puzzling to some of those who have concerned themselves with the Greek dress, but its explanation is as simple as that just given of the ‘pleat’ at the top of the dress in front. It must be noted that it is only when the dress is full that this arch will appear. If it be scanty, so as only to go round the figure without much to spare, the line must be straight, and we see it as such in earlier work, such as the standing figures from the pediment at Olympia.

At the back it seems to have been the custom to pull the dress up through the girdle to a less height, and in this way to produce a sort of train, which must have greatly improved the look of the robe when worn by a figure in movement. No. 9 shows the dress as far as it has now been carried, and such a costume was at any rate sufficient for the goddesses Hera and Athena, who sit draped in this fashion in the assembly of the gods on the Parthenon frieze.

The dress as now constituted lacks one element observable in the front view of the Caryatid in No.8. It will be seen there that part of the material is folded over at the top and falls at the front and at the back as far as the waist. The lower edge of this, which is single, is easily to be distinguished from the double roll which falls over when the robe is pulled up through the girdle; but it follows the same arched line as the latter, because at the sides the length is not merely the perpendicular depth of the fall which we see in front, but the whole 30 inches or so from the shoulder attachment to the outer corner of the stuff where the figure is holding it in No. 6. To keep these ends clinging closely to the form the corners are weighted, and this can often be seen on the monuments. On the other side of the figure, where the dress is not open but is folded round, the material forming the fall passes under the arm in a sort of bag.

This turning over of the stuff, for which extra length must be allowed, may have been due to the desire to obtain additional warmth over the upper part of the body. No. 11 shows it complete; the fact that it is not sewn up on the open side being demonstrated by the exposure of the limb. The dress may, however, be sewn up along the whole length of the open side without thus involving any alteration of its arrangement. What must seem to us a defect in the dress still remains, and this is the exposure of the flank under the arm between the shoulder and the girdle. This unfits the dress for fancy use in modern days, and must, one would think, have counteracted entirely the effect of the reduplication of the stuff over chest and back by giving admission to the cold. The sewing up of the open side makes no difference here, as it is the top of the dress, not the upper part of the long side, that is open; and the aperture is just as apparent on the side where there is no seam, as on the attendant in No. 5.

The inconvenience in question is at once removed when the dress is fastened along the arm in the manner of a sleeve. Such fastenings are shown in No. 10, and the completed result on the right side of No. 12, while a reference back to No. 6 will show, what must never be forgotten, that when a sleeve is used the arm or hand will always issue out of the top of the dress; never out of the side. A sleeve of this kind cannot conveniently be worn with the fold-over, as this would always be flapping over the arm when extended or moved.

With the simple dress of No. 9 however there is no difficulty; but the use of the sleeve necessarily modifies the double fall of the dress as it is pulled up through the girdle. The superfluity of stufF at the sides, which gave the arched line of the fall, is now required for the sleeve, as it is essential that there should be fullness enough under this to allow the arm to move freely. It is therefore drawn up as far as possible through the girdle, and hangs in ample folds under the arm as in No. 12. It is there confined by a band passing under the arm and over the shoulder after a fashion exhibited on the monuments.

It is a very curious fact that a sleeve of this kind, which may be quite short like that of the Chiaramonti Niobide, and only fastened once or twice along the arm; seldom or never makes its appearance on the monuments as a future of what is clearly the woolen Doric tunic. The sleeve is, of course, very common, but it almost always occurs in connexion with the other form of the tunic, where the stuff seems more voluminous and its fabric linen. In principle, however, the Dorian tunic, when worn without the fold-over, could always, if desired, supply the wearer with a covering for the arms.

HERODOTUS tells us that the so-called Dorian tunic, noticed in the preceding article, was the original attire of all the Greeks, and it appears that the Homeric dames, whose white arms and shapely ankles seem to have been in evidence, were already attired in this simple and convenient fashion. On one occasion, however, in early Attic history the Athenian ladies used the pins or clasps of their tunics for murderous assault, so that a sumptuary law was passed obliging them to alter their attire to the Ionian fashion, and they accordingly ‘changed to the linen chiton, with the intention that they should not use any more’ such dangerous fastenings. This passage is the locus classicus for the character of the ‘Ionian’ tunic, which has been already referred to as differing from the Doric.

On the strength of it it has been maintained that the Ionian tunic was not held together by clasps of any kind, but by seams; while some believe that it was shaped by the scissors with a sleeve formed by cutting and sewing like that of a modern blouse. The prototype of such a dress would naturally be sought among the flowing robes of Orientals, and when it was pointed out that the word ‘chiton,’ used commonly in Greek for this dress, was of Semitic derivation and meant a linen garment. It appeared established that the Ionian tunic was borrowed from the East, and was of an entirely different form and character from the more purely Hellenic Dorian dress.

A shape for the dress was suggested by Studnicska, who in 1886 published a diagram of it, while other writers have since then figured and described it. It is elegantly described in Smith’s ‘Dictionary of Antiquities’ as made when ‘two rectangles of cloth have been sewn together on three sides, in such a way that a sack is formed with a hole in the bottom for the head to go through, and two holes at the sides for the arms.’ Such a dress is shown in No. 23 on Plate IV, and the reader can judge of the artistic possibilities of it, in comparison with the dresses of the same material worn by the model in the fashion contended for in these articles in Nos, 17 and 19.

To begin with, the dress is about half as wide as the minimum width which experiments show to be needful for richness in folds. It is described in Pauly’s’ Real Encyclopadie’ and elsewhere as the same width as the distance between the elbows of the wearer when the arms are extended sideways. It should as a fact be quite as wide as the whole stretch of the arms, from finger tips to finger tips. One writer says the width of the dress ‘being half the full span of the wearer with the arms stretched out, a long hanging sleeve is thus obtained’; but as a fact there is no material for a sleeve of any length or richness, while the straight seam of the top of the dress from the neck to the elbow cannot possibly allow of that graceful clinging or the stuff to the limb, secured when it is draped along it in ample fullness with fastenings at intervals.

Then, again, the notion that the tunic was sewn up along both sides is surely a very strange one. The seam up one side of a dress is at times shown in sculpture, but who ever saw on a monument a seam up both sides? The second seam was evidently suggested by the desire to avoid cutting a hole in the stuff on the closed side to get the arm out, but soon as it is recognized that the arm always issues out at the top of the dress, and not out of any part of the sides, this gratuitous second seam may very well be dropped.

The supposed Ionian tunic of these descriptions is in fact a prim and scan ty little shift that lends itself to no charm or variety of cast, and it is time that it should cease to do duty for the sweeping raiment of Ionian Greeks, whose studied elegance in costume and coiffure is attested alike by the monuments and by literature.

The dress impugned has been devised to correspond with the traditional interpretation of the passage from Herodotus. This interpretation is, however, contradicted by the monuments themselves. These proclaim almost with one voice that the ‘Ionian’ tunic shown on them is not sewn on the arm, but is fastened with small clasps or buttons, while, so far as can be judged, the shoulder fastening, which is very often concealed by the hair, is of the same character. Nay, more, on some draped female figures in the Museum at Mykonos, there are actually to be seen remains of small bronze fastenings let into the marble, that served as attachments of the sleeve. In many of the similar figures that form the chief attraction of the Acropolis Museum at Athens, the attachment is figured in the marble as a small button. The same is the case in innumerable instances on the vases, though the painter here does not always take the necessary pains to exhibit the separate fastenings.

No one, indeed, who started from a study of the monuments, especially those of sculpture, would have the least hesitation in deciding that the dress was clasped at intervals along the arm and not sewn. is only the influence of a traditional literary interpretation that has blinded the usually wide-open eyes of the professed archaeologists.

The truth is that when Herodotus tells his readers that the change of dress he refers to was brought about … all he means is that the long pins, or brooches furnished with such pins, were given up for another kind of fastening. His words do not necessarily imply the substitution for the pins of a seam. The exact construction of these small fastenings is a matter for conjecture, but they cannot have contained pins of a dangerous size.

On the other hand the Dorian tunic was held as a rule by a single fastening, and this, especially as the stuff was comparatively heavy, was naturally large and strong. Of its nature we are not fully informed, as it is very seldom indicated on the sculptured monuments. It appears occasionally on vases in the shape of a long and formidable pin with an elaborate head, and a point that projected upwards and that must certainly have needed a point protector, such as was found in connexion with pins of the kind at Hallstatt. Although, however, the shoulder fastening of the tunic is generally ignored by the carver, the attachment of the chlamys at the neck or on the shoulder is very commonly rendered in sculpture, as, for instance, on the Phigaleian frieze, and appears there in the form of a round disc. This was probably not a button, but a fibula with a pin below, and this pin might have been large enough to be serviceable in assault. A brooch of the kind has been used in the experiments with the Dorian tunic shown on the plates.

There is, however, one conspicuous monument of undoubtedly Ionian sculpture that seems at first sight to offer the much-needed monumental support for the literary thesis. This is the Harpy Tomb from Lycia, in the British Museum. There on the western side (see No. 24) sits enthroned a stately lady, who holds out a phiale in her right hand, and exhibits in so doing an arm covered with an ample sleeve to the wrist. All down the front of this arm runs a plain stripe with an incised line at each side and down the centre, and the stuff is treated on each side of this stripe with the conventional lines that denote the folds of a thin linen fabric.

Here at least we appear to find distinctly represented a seam, but the indication is deceptive. Apart from the fact that this is not the natural position on the arm for a seam, the stripe is really intended to serve as a basis for the work of the painter, who would represent thereon in color the wavy edges of the stuff and the intermittent points of attachment. That this is the true explanation is suggested by the colored reproduction of one of the draped female figures from the Acropolis, given in the German official publication ‘Antike Denkmaeler,’ I, Plate 19. There on the right arm the green pigment that indicated these fastenings is still visible, and the Harpy Tomb figure must originally have exhibited something of the kind. A confirmation of this view of the most convincing kind can be found on one of the draped female figures from the Parthenon known as ‘The Fates.’

The two figures which form the familiar group show on their right arms the dress drawn together at intervals with the gathering in of the fabric at the points of attachment, though the actual clasps are not plastically rendered. In the case of the third figure, however, who sits nearest to the centre of the pediment, the sleeve all the right arm is treated almost exactly as is that of the figure on the Harpy Tomb.

There is no plastic indication of the drawing together of the stuff, but a flat stripe is left on which the painter would add what was necessary to complete the effect. It is a curious example of a little survival of archaism in the otherwise mature pediment compositions, and unless we imagine this figure to have been dressed differently from her sisters, which no reasonable spectator would believe, we must accept an explanation which covers also the earlier Ionian example just referred to.

It this be accepted then it follows that the sleeve was not a cut and shaped one, for such a sleeve would not be closed with temporary attachments. Independently, however, of the seam, Amelung, in Pauly’s ‘Encyclopadie,’ argues that the form of the sleeve on the Harpy Tomb shows it to be a distinct piece apart from the rest of the dress. This can be tested by experiment. No. 18, Plate IV, exhibits a pose and costume sufficiently like those in the relief in question, and it will be seen that a satisfactory sleeve can readily be made on the simpler system.

Another early monument that has every appearance of belonging to the Ionian School seems conclusive on the point here urged. This is the so-called Leucothea relief in the Villa Albani, where the standing figure to the right of the relief wears a sleeve that the carver has quite unmistakably represented as in one piece with the dress.

It is not of course denied that the needle and thread were employed in connexion with the Greek costume. The tunics, both Dorian and Ionic, might be sewn up on the open side, and in these cases they were sewn up entirely, for the term ‘partially closed Dorian tunic,’ found in some of the books, rests on a misunderstanding of the dress. So far as practicability goes, the dress might be sewn on the shoulder and along the arm instead of being caught at intervals by the small clasps. On the left arm of the model in No. 22 the dress is closed by such a seam, and so far as can be judged the long tunic worn by the famous bronze charioteer from Delphi is similarly treated, see No. 20. For a man who may have been a bachelor such an arrangement would be convenient, and he would not mind the sacrifice of appearance for the sake of avoiding the tiresome fastening and unfastening of numerous clasps.

There is no question, however, that the sacrifice of appearance would be a very signal one, for the system of intermittent fastenings is of the very essence of the Ionian tunic as a vehicle of artistic effect. To realize all its aesthetic capabilities, it is necessary to consider with the tunic the over-robe or himation. It is the contrast of the larger folds of the thicker fabric with the crisp and delicate ones of the tunic that largely determines this artistic effect, and it is only with an ample linen chiton, the fastenings of which are of the kind here spoken of, that sufficient variety and richness can be obtained.

Nos. 17 and 20 are intended to show the natural formation of these folds in a stuff properly disposed about the figure and itself very thin and soft through age. By the Greek sculptor the form is plastically rendered in all its fullness and beauty beneath the robe, but it is quite a visionary notion that he swathed his unfortunate model in wet drapery to make this cling closely to the limbs. As a fact the drapery lies in nature over the form just as it lies in Pheidian sculpture, and the actual fall of the stuff when suitably cast will hardly ever fail to produce some passage or passages of rare and delicate beauty that would not be out of place on a fine statue of the fifth century. It adds to our appreciation of the consummate genius that guided the Greek chisel when we see how near it kept to nature while achieving as a whole the most ideal beauty.

For example, No. 21 exhibits something sufficiently like the pose and drapery of the reclining ‘Fate’ from the Parthenon, to enable us to realize what the sculptor must have had before him in nature. The baring of the shoulder, which would be impossible with a sewn tunic, is easily brought about by undoing a couple of the upper fastenings of the clasped garment, while the value of the intermittent attachments which gather in the stuff at certain points is apparent in the fall of the sleeve from the left arm of the model. No. 25 shows how, if all the clasps be undone, the dress is resolved again into its simple dements, while Nos. 17 and 19 illustrate the use of the subsidiary bands crossing in front of the bosom or at the back. When they cross at the back, as in No. 19, they are bound tolerably closely round the arm at the shoulder, and in this way conveniently confine and shape the sleeve. When crossed at the front they do not specially affect the sleeve, but define the bust and give opportunity for delicate effects in the arrangement of the smaller crisply-wrinkled folds.

With the Ionian tunic thus treated there is constantly combined the ample woolen mantle, which not only kept its wearer warm during a winter that was by no means always mild, but ministered to the pleasure of the eye in composition and contrast. Half the artistic beauty of Greek draped statues and reliefs depends on the studied contrasts thus brought into view, and there are passages in these that are absolutely satisfying to the aesthetic sense, and yet have nothing to offer but this simple composition of broadly-treated with richly-detailed surfaces. It was a very common cast for the end of the himation, which must measure at least four yards by two, to be thrown from the back over the left shoulder and for the mass of the drapery to be brought round over the back and front of the figure and finally thrown over the left shoulder from the front.

The handmaid in No. 14, Plate III, is in the act of draping her mistress in this fashion. For outdoor wear, part of the mantle could be drawn over the head in the form of a hood, while seated female figures are commonly satisfied with wrapping the cloak round the lower limbs. A part from the marbles and the vase paintings, we find this mantle worn in a hundred graceful fashions in the so- called Tanagra figures.

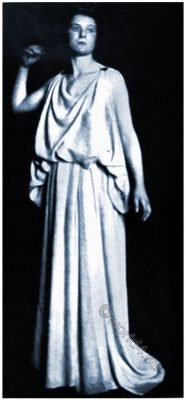

Occasionally by women, and, at any rate in the monuments, constantly by older men, we find the himation worn alone without any tunic. No. 13, Plate III, shows a cast suggested by the beautiful relief of the female dancer in repose from the theatre at Athens. In all these cases there is no brooch or other fastening, but such attachments are used in other fashions of the costume. That in which it is worn falling at the back and clasped on both shoulders at the places where the tunic is fastened (see No.2 on Plate 1) a fashion affected by the Caryatids of the Erechtheion, and the Eirené of Cephisodotus at Munich, seems a little awkward. One does not see exactly how a mantle thus attached can conveniently have been brought into service, and the weight of it must have caused a drag on the shoulders. The himation is sometimes doubled, and, passing under one arm, is clasped on the other shoulder. Both males (Apollo in the relief from Thasos in the Louvre) and females (Diana from Gabii in the Louvre) wear wraps of this fashion.

In the form of the small military cloak or chlamys, worn commonly by youths and warriors on the sculptured friezes, the drapery is used more as an element in the decorative pattern than as clothing for the body, and streams freely in the wind in whatever shape is required by the composition. In the Parthenon frieze it is used more soberly; Hermes in the Thasos relief really wears it as clothing.

The only form of the overdress that does present real difficulties is that worn by many archaic draped female figures, and shown in Nos. 15 and 16 on Plate III. One difficulty is to know whether the folded garment shown as white in the illustrations is in reality a scarf-like wrap thrown round the upper part of the form, or the upper and turned-over part of a doubled himation. In other words, is the skirt below the wrap of a piece with the dress that shows above the wrap, or is the skirt formed by the lower part of the wrap itself that completely conceals the underdress?

This question, which has been argued by Kalkmann, Holwerda and other archaeologists, is, to the writer’s mind, solved by some archaic terra-cottas in the museum at Athens, published by Winter in the Jahrbuch for 1893, the coloring of which seems to prove that the garment is really an independent scarf-like piece out of connexion with the drapery that falls below it.

Given a motionless wearer of imperturbable patience, and plenty of pairs of hands to fold and to hold, the dress can be formed by making the long folds on the diagonal of the stuff, and gradually bringing these to the vertical in relation to its width, when the parts arc reached where the folds must be short. Unless the strips be made inconveniently narrow, these short folds in the front of the figure will still be too long, and now comes what appears to be the secret of the dress. The upper edge of it, with all the folds, is tightly rolled over so that it is shortened in the front, while at the same time the folds are kept in their places. A scarf thus arranged will sustain itself, but of course when a band is drawn tightly along it under the roll, its security is greatly increased. There are cases in which it is fastened on both shoulders instead of only on one (see No. 16), while it is sometimes clasped along the arm so as to form a kind of sleeve.

This curious form of the overdress can be made by folding a long and narrow rectangular strip, but it is easy to see that it is an unpractical vestment, tiresome to put on, and liable, if not fastened, to come out of its elaborate creases at a moment’s notice. As a fact, the folds are very often fixed by means of a band that binds the wrap tightly round the person, as in No. 15, but this is not always the case, and it is possible so to arrange the stuff that it will sustain itself in its folds, but only on a motionless figure. If the model move, the result is a debacle. Hence it seems probable that the dress, which in its elaboration and prim artificiality suits the archaic times, was really evolved for use on the xoana, or dressed-up doll-like idols of wood, so beloved of the people.

Source: The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. London: Savile Pub. Co.; New York: S. Buckley, 1903.

[wpucv_list id=”136457″ title=”Classic grid with thumbs 2″]Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.