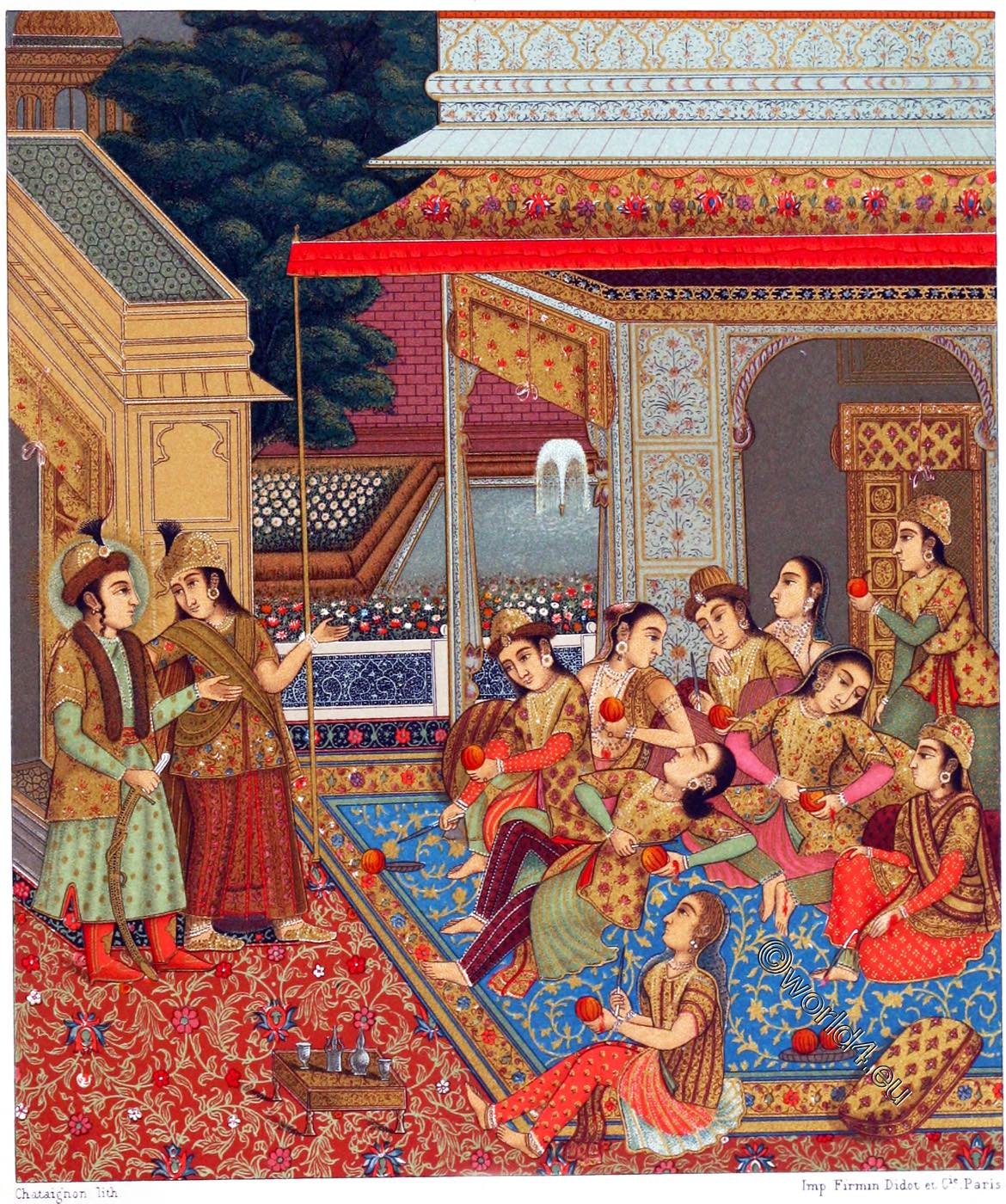

INDIA. INNER COURTYARD OF AN INDIAN HAREM.

Facsimile of an Indian-Persian miniature depicts Zuleika introducing Joseph to her friends who are busy peeling oranges.

The story about Zuleikha and Joseph.

Facsimile of an Indian-Persian miniature, formerly owned by Ambroise Firmin-Didot in Paris. Zuleika, so called in the Indian legend the wife of Potiphar, introduces Joseph to her friends who are busy peeling oranges. Their expressions and movements reflect their amazement at the beauty of the Israelite Selavon. One of the women drops her knife in surprise.

The story of Zuleikha is told in the Middle Ages Jewish Sefer ha-Jaschar, Book of the Righteous, a commentary on the Torah, and in the Koran, where she was mocked by other aristocratic Egyptian ladies, her circle of friends, because she was in love with a Hebrew slave boy.

Zuleikha invited her friends to her house and gave them all oranges and knives to peel them with. While they were engaged in this task, Zuleikha let Joseph walk through the room. Distracted by his beauty, all the ladies accidentally cut themselves with the knives and shed their blood in the process. Zuleikha then reminded her friends that she had to see Joseph every day. After this incident her contemporaries no longer mocked her.

Potiphar, also known as Aziz in Islam, is a figure in the Hebrew Bible and the Koran. He is the captain of the Pharaonic Guard, who is said to have bought Joseph as a slave and, impressed by his intelligence, made him master of his house.

Unfortunately, Potiphar’s wife, who was known for her infidelity, had taken a liking to Joseph and tried to seduce him. When Joseph rejected her advances and ran away, she took revenge by falsely accusing him of wanting to rape her, and Potiphar had Joseph locked up. Since execution was normal in rape cases, the story implies that Potiphar had doubts about the portrayal of his wife.

What happened to Potiphar afterwards is unclear; some sources identify him as Potipherah, an Egyptian priest whose daughter Asenath Joseph married. The false accusation of Potiphar’s wife plays an important role in Joseph’s account, for if he had not been imprisoned, he would not have met the fellow prisoner who introduced him to Pharaoh.

This story became a very common theme in Western art during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, usually depicting the moment when Joseph tears himself away from the bed with a more or less naked figure of Potiphar’s wife. Persian miniatures often illustrate Yusuf and Zulaikha in Mawlanā Jami’s (d.1492) Haft Awrang (“Seven Thrones”).

Source: History of the costume in chronological development by Auguste Racinet. Edited by Adolf Rosenberg. Berlin 1888.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.