French fashion history. Middle Ages. 1422 to 1483.

Reign of Charles VI, 1395 to 1422, called the Beloved (French: le Bien-Aimé), Charles VII, 1422 to 1461, called the Victorious (French: le Victorieux) and Louis XI, 1461 to 1483, called “Louis the Prudent” (French: le Prudent).

Content:

Taste in dress becomes purer – Heart-shaped head-covering, the “cornette,” and the “hennin ” in the reign of Charles VI – Husbands complain – Preachers denounce – Thomas Connecte declaims against the diabolic invention – Brother Richard tries to reform it – The “hennin” gains the victory – Costume of Jeanne de Bourbon – “Escoffion” – An absurd figure – Gravouère – Isabeau de Bavière – Gorgiasetès – Tripes – Splendour of the court – Agnes Sorel – “Coiffe adournée”; diamonds; the carcan – Walkingsticks.

Middle ages 14th to 15th century.

It is a curious fact, of more frequent occurrence than might be imagined, but the terrible Hundred Years’ War, which cost so much French and English blood, in nowise diminished women’s passion for dress and fashion, whims and extravagance of all kinds. It must even be acknowledged that this melancholy period of our history was remarkable for the splendour of its fashions.

From the time of the Capets there had been much variation in dress and in luxury. The taste of the nation was stimulated and improved by foreign importations. Emblazoned garments had become a thing of the past.

Heart-shaped head-covering.

In the reigns of Charles VI. and Charles VII. especially caprice began to play an important part in the dress of women. The “beguins,” or hoods, were changed at first into high heart-shaped head-gear, with two wide wings fastened to the head with wire and bearing a strong resemblance to the sails of a windmill.

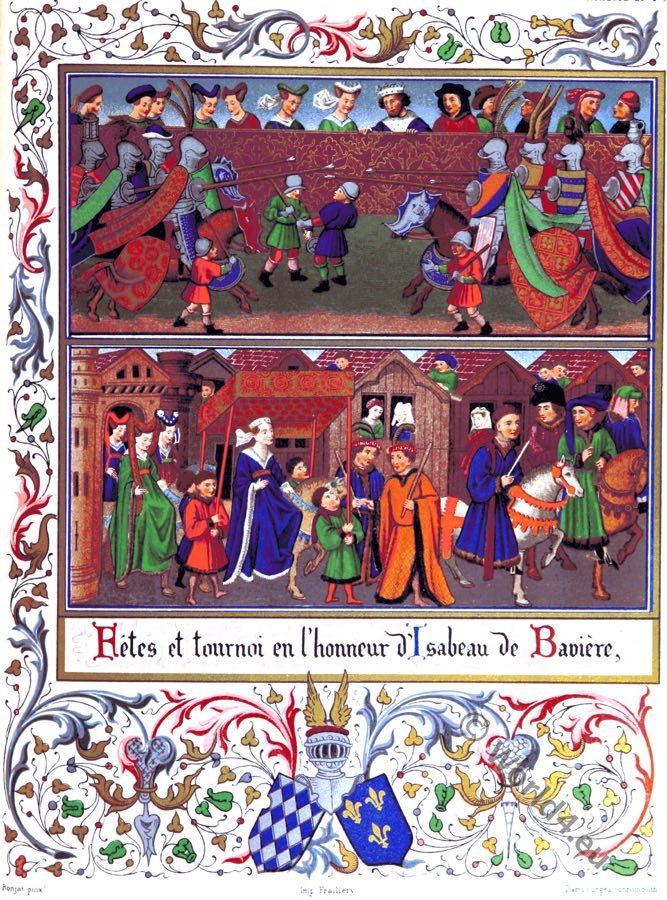

Next, the heart-shapes having been criticized by the clergy were transformed into “Hennins,” the non plus ultra of fashion, and were of a most prodigious height. Very different from the masculine head-gear bearing the same name was the “Cornet” or “Hennin “worn by women. This was a kind of two-horned head-dress, with horns about a yard high, which was introduced into France by Isabeau de Bavière, the wife of Charles VI. The “Hennins“ were made of lawn stuffy starched and kept in shape by fine wire, but were of less exaggerated size.

Such a novelty was irresistible; all the ladies eagerly copied the Queen, and vied with each other as to who should wear the most handsome head-gear, “peaked like a steeple,” says Paradin, and the tallest horns. From these horns there hung like flags, crape, fringe, and other materials, falling over the shoulders. Such head-dresses were naturally very expensive, and husbands were loud in complaint.

Matrons and maidens alike “went to great excesses, and wore horns marvellously high and large, having great wings on either side, of such width, that when they would enter a door it was impossible for them to pass through it.” The height of the hennins was so great that a small woman looked at a distance like a moving pillar.

In mourning, however, the Cornette was rolled round the throat and thrown backwards. “Never, perhaps,” observes Viollet le Duc, “did extravagance in head-gear reach such a pitch with the fair sex as during those melancholy years from 1400 to 1450; the hair itself formed but a small part of the head-dress; hoods, couvre-chefs, chapels, horns, cornettes, hennins, twists, knots, frémillets, and chains were built up into the most extraordinary edifices.” Yet it was far worse than all this in England, where eccentricity and caprice reached a height never attained at the French court.

Confessors in France, and monks especially, added their animadversions to those of grumbling husbands. They considered the “Hennin” as an invention of the Evil One, and a deadly warfare against the obnoxious article was soon organized.

Jean Wauquelin presenting his book to Philippe le Bon (Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy as Philip III, 1396 -1467) in the presence of the boy Charles le Téméraire (Charles the Bold 1433 – 1477), Nicolas Rolin and Jean Chevrot.

The Hainaut Chronicles is an illuminated manuscript in three volumes which traces the history of Hainaut County until the late fourteenth century.

Philippe le Bon (1396 -1467) et Charles le Téméraire (1433 – 1477) enfant recevant la dedicate d’un livre. Miniature des Chroniques de Hainaut. Rogier van der Weyden. Conservé à Bruxelles, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Manuscripts, MS.9242.

Thomas Connecte declaims against the diabolic invention.

In 1428 a Breton monk, named Thomas Connecte, preached throughout Flanders, Artois, Picardy, and the neighbours provinces. He travelled from town to town, riding on a small mule and followed by a crowd of disciples on foot. On reaching his destination he said mass on a platform expressly prepared for him, then he preached against Non-juring priests, the “Hennins” of great ladies, and also against gamblers, calling upon the latter to burn their draught-boards and chess-boards, cards, ninepins, and dice.

He called on children to help him, frequently shouting out the first, by way of example, “au hemming” whenever he caught sight of any woman wearing a high head-dress in the streets; and if she failed to find a speedy refuge in some house she was soon covered with mud, dragged in the gutter, and sometimes severely wounded. Connect was looked upon by the people as an admirable reformer, but he failed to reform the head-gear of women; victory remained with the hennin.

Brother Richard tries to reform it.

Another monk, a Franciscan, one Brother Richard, followed in the steps of Connect the Carmelite. On the 16th April, 1419, he began a course of sermons at the Abbey Church or St. Genevieve, which lasted till April 26th. He ascended the pulpit at five in the morning, and remained there until ten or eleven o’clock. He, too, endeavoured to reform the dress of women and their towering head-gear. His discourses occasioned some disturbances. After the tenth sermon Brother Richard received his dismissal from the Governor of Paris.

The “hennin” gains the victory.

It could not be said that the holy men preached in the desert, for wheresoever they lifted up their voices there were large audiences, and for a time the obnoxious Hennins disappeared; but only for a time. “The ladies,” wrote Guillaume Paradin, the historian, “imitate the snails who draw in their horns, and when the danger is over put them out farther than ever; and in like manner Hennins were never more extravagant than after the departure of Brother Thomas Connecte”.

Finally, whether their husbands spoke on behalf of economy, or their priests appealed to the decrees of the Church, victory remained with the women. They only gave up the Hennins from a caprice similar to that which had invented them. No one will expect to find Frenchwomen more constant or more economical in dress than their husbands. In the reign of Charles V., beauty had already asserted its claims, and coquetry filled the heart of women who sought for admiration. They gave up the fashions of the Middle Ages, and uncovered their bosoms; in addition to Hennins they wore padded head-dresses with horns, or pieces of stuff cut out and laid one upon the other like the petals of a flower.

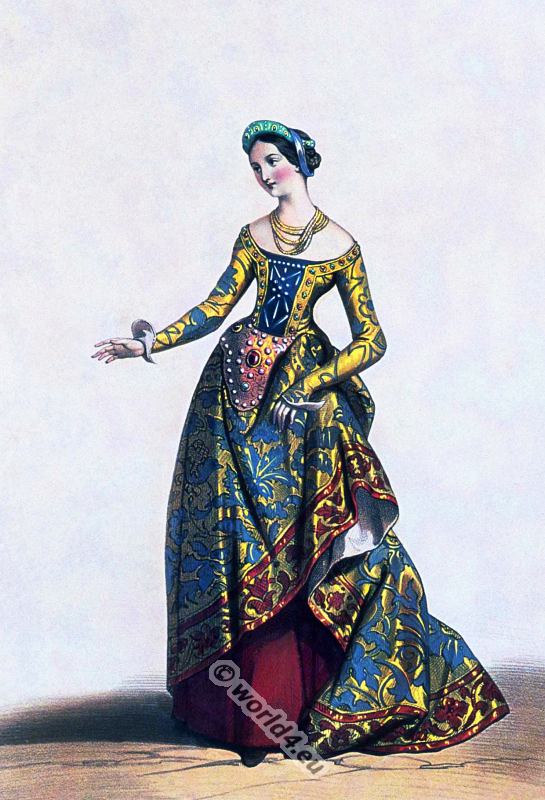

At the beginning of the 15th century, scalloped sleeves were attached to the corsets, or rather to the bodices, which were separated from the skirt behind, ending in a horizontal fold on the hips, while in front they were ungirdled, and reached down to the feet. These bodices were cut very low in the neck; the shoulders were slightly covered by a hood.

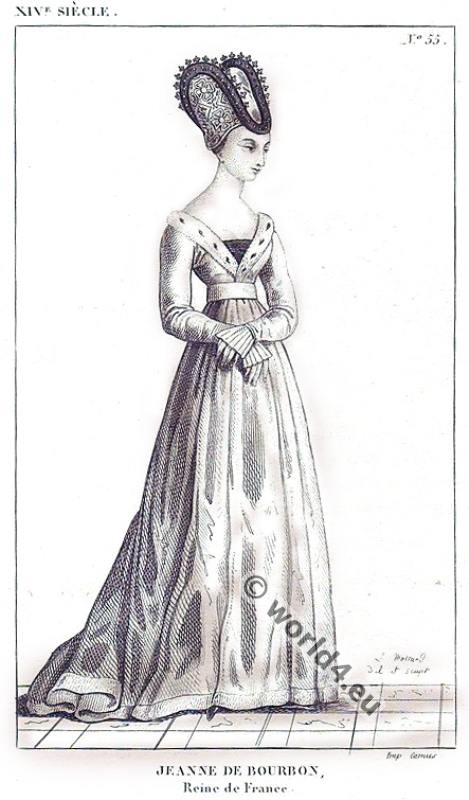

Costume of Jeanne de Bourbon

Jeanne de Bourbon, the wife of Charles V., wore “royal robes wide and flowing, en Sampues pontificates, that they call “chaps” or copes, that is, “mantles of gold or silk covered with jewels.” The wives of barons wore earrings, “outrageous toes to their shoes, and they seemed to be sewn up iIl their too scanty garments.”

The expression “too scanty” was probably applied to the mantilla introduced by Queen Jeanne, and which was called a “corset.” The mantilla reached to the waist both in front and behind; in winter it was made of fur, and in summer of cloth or of silk; it had a sort of busk covered with gold braid, and matched in color the borders of the surcoat, thus relieving the monotony of the lines as well as the sameness of coloring. Those ladies who wore trains to the skirts of their surcoats, used to tuck them up for walking.

The surcoat, in fact, was very similar to a gown, and its dimensions soon became so enormous, that, as we learn from Christine de Pisan, a man-milliner of Paris made a “cotte hardie” for a lady in Gâtinais, in which were five yards, long measure, of Brussels cloth. The train lay three quarters of a yard on the ground, and the sleeves fell to the feet. This, no doubt, was an expensive costume. There were women whose surcoats were longer than themselves by a full yard. They were obliged “to carry the trains thereof over their arms, and there were long cuffs to their surcoats hanging to the elbows, and their busts were raised high up.”

The Escoffion

The fashions of head-dresses changed from bare heads to crèpines, and coifs with tow underneath, and stuffed “à la escoffion,” a sort of padded beretta. The name “escoffion” became afterwards popularly used for the head-dress of the women of the lower orders, or the peasant-women, or that of women with their hair badly done. The fish-women, when quarreling, had a trick of tearing off each other’s escoffions.

At the same period, the most absurd adjuncts to dress were daily invented, causing that charming poet, Eustache Deschamps, to exclaim,- “A tournez-vous, mesdames, autrement, Sans emprunter tant de barribouras.” In the reign of Charles VI., the houppelande (houppelande or houpelande is an outer garment, with a long, full body and flaring sleeves, that was worn by both men and women in Europe in the late Medieval period) was the fundamental article of women’s attire, but passing from one extravagance to another, they at last adopted the strange fashion of giving an abnormal development to the front of the figure! This continued in fashion for forty years.

In the Charvet Collection there is an earring of the fifteenth century, ornamented with a polyedrus in incrusted purple glass. We still possess framed rings (bagues chevalière) and other ornaments of that period, and, in particular, one silver-gilt medal in the shape of a heart; on the reverse the Virgin and St. Catherine are represented in mother-of-pearl. Enamelled gems were much in vogue among the nobility during the reign of Charles VI.

There were also enamels of flowers, insects, domestic animals, and small ornamented human figures, initials, and mottoes. A little instrument was invented for parting the hair. It was a sort of stiletto or bodkin called a “gravure,” generally made of ivory or crystal, and sometimes mounted in gold. It remained in use as an article of the toilet during the whole of the Middle Ages.

Isabeau de Bavière. Queen consort of France.

The custom of wearing bracelets and necklaces dates so far back as the reign of Charles VI., when Isabeau de Bavière (Isabell of Bavaria 1370-1435) introduced fashion of trinkets. They were called “gorgiasetès” in the language of the day, and it used to be said of persons whose dress exceeded the limits of decorum, that they dressed “gorgiasement”, (… en France les pompes et les gorgiasetez pour bien habiller superbement et gorgiasement les dames). Isabeau also patronized very long trained gowns, and mantles with trains, carried by ladies’ maids or pages.

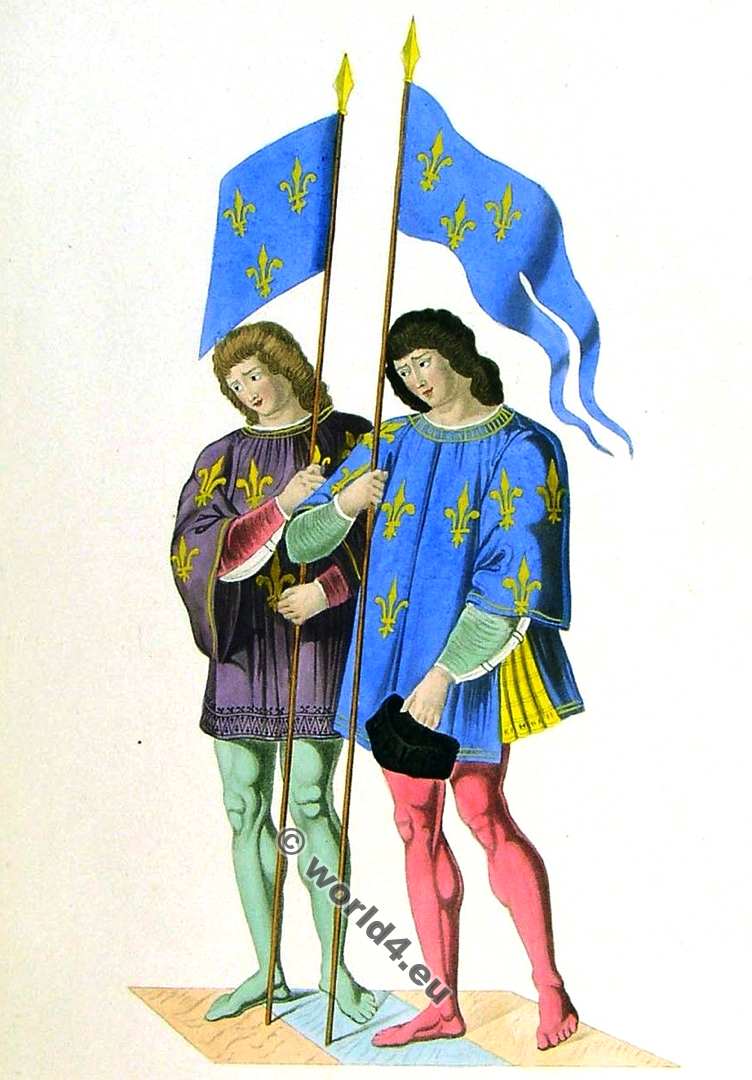

This custom still prevails at court; likewise liveries of certain colors to distinguish all the household of great nobles. Liveries, which had already existed for several centuries, became much more prevalent in the reign of Charles VI. The “cotte hardie” (during the Middle Ages a sleeved tunic, who wore both sexes and all classes) was long and flowing, but was confined at the waist, partially revealing the outline of the figure. It was lined with rich fur.

As the surcoat concealed the cotte (Cotte, even coat or cotta, was a similar long-sleeved tunic slip dress) everywhere except at the sleeves, the latter were tucked up very high by the wearers so as to display the valuable material of the “cotte hardie.” They also made an opening in the surcoat in order to show the girdle. Sermons were vainly preached against the latter fashion.

Isabeau de Bavière, the sovereign arbiter of dress, had fanciful tastes which became law to other ladies, both in the matter of head-gear and of toilet generally. There appeared successively the “tripe,” a sort of light jockey cap made of knitted silk; the “attar,” (festive dress) stuffed with tow; and, lastly, head-dresses of such towering height that the ceilings in the Castle of Vincennes, then a royal abode, were raised to enable the ladies to move about in comfort and safety. It was of course absolutely necessary to be beautiful, to attract admiration, to dazzle the crowd, to make use of every device to prove that universal homage was both deserved and obtained.

To this end, therefore, the French ladies heaped ornament upon ornament. Beautiful prayer-books were in general use, and indeed formed an integral portion of fashionable attire:- “Heures me fault de Notre-Dame, Si comme il appartient à fame (femme) Venue de noble paraige, Qui soient de soutil (subtil) outrage, D’or et d’azur, riches et cointes, Bien ordonnèes et bien pointes, De fin drap d’or tres bien couvertes; Et quand elles seront ouvertes, Deux fermaux d’or qui fermeront.”

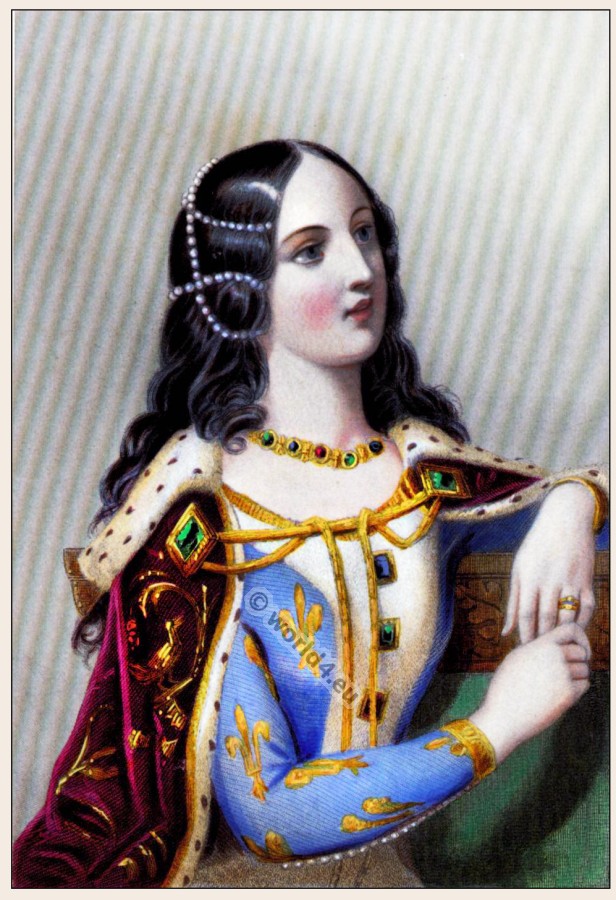

Isabelle de Valois. (Also known as Isabella of France; born November 9, 1389 Paris; † September 13, 1409). Isabelle was the third child and second daughter of King Charles VI of France and his wife Isabeau de Bavière.

These prayer-books were carried in cases suspended to the arm or waist. Until the reign of Charles VI. the under-garments of Frenchwomen were of coarse stuff or serge, that is, of wollen material. Isabeau de Bavière was the first to wear a linen chemise; she possessed, however, two only.

The tine ladies of the fifteenth century naturally imitated her, and in order to show that they wore linen under-garments, they made openings in their gown sleeves that the chemise might be seen; they even opened their skirts on the hips in order to display the length of the chemise; and they ended by having those garments made of fine linen only in the parts visible to the public, the rest was in coarse stuff or serge. Linen chemises were regarded as luxuries until the time of Louis XI. They were called “robes-linges.”

In the reign of Charles VI., the dress of servant-maids was generally composed of three pieces; a bodice of one color, a tucked up skirt of another, and a petticoat with a kilted flounce at the edge, such as are worn at the present time. The hair was covered with a kind of cap “à la musulmane.”

Such is the costume we find represented in the miniatures of the latter period of the fourteenth century. Everyone knows what evil times had befallen our country under Charles VI. The English were masters of a great part of France, at the time that Charles VII. ascended the throne and was called in mockery “King of Bourges.” That affront was wiped out by Joan of Arc.

At that period, Fashion was confined for a long time within narrow limits; but no sooner had France returned to her normal state, than the court of Charles VII. displayed a magnificence of which the sovereign set the example on the occasion of his entry into Rouen. He rode a palfrey caparisoned in blue velvet, embroidered with gold lilies, and the “chanfrein,” or nose-piece, was of plates of solid gold withostrich plumes.

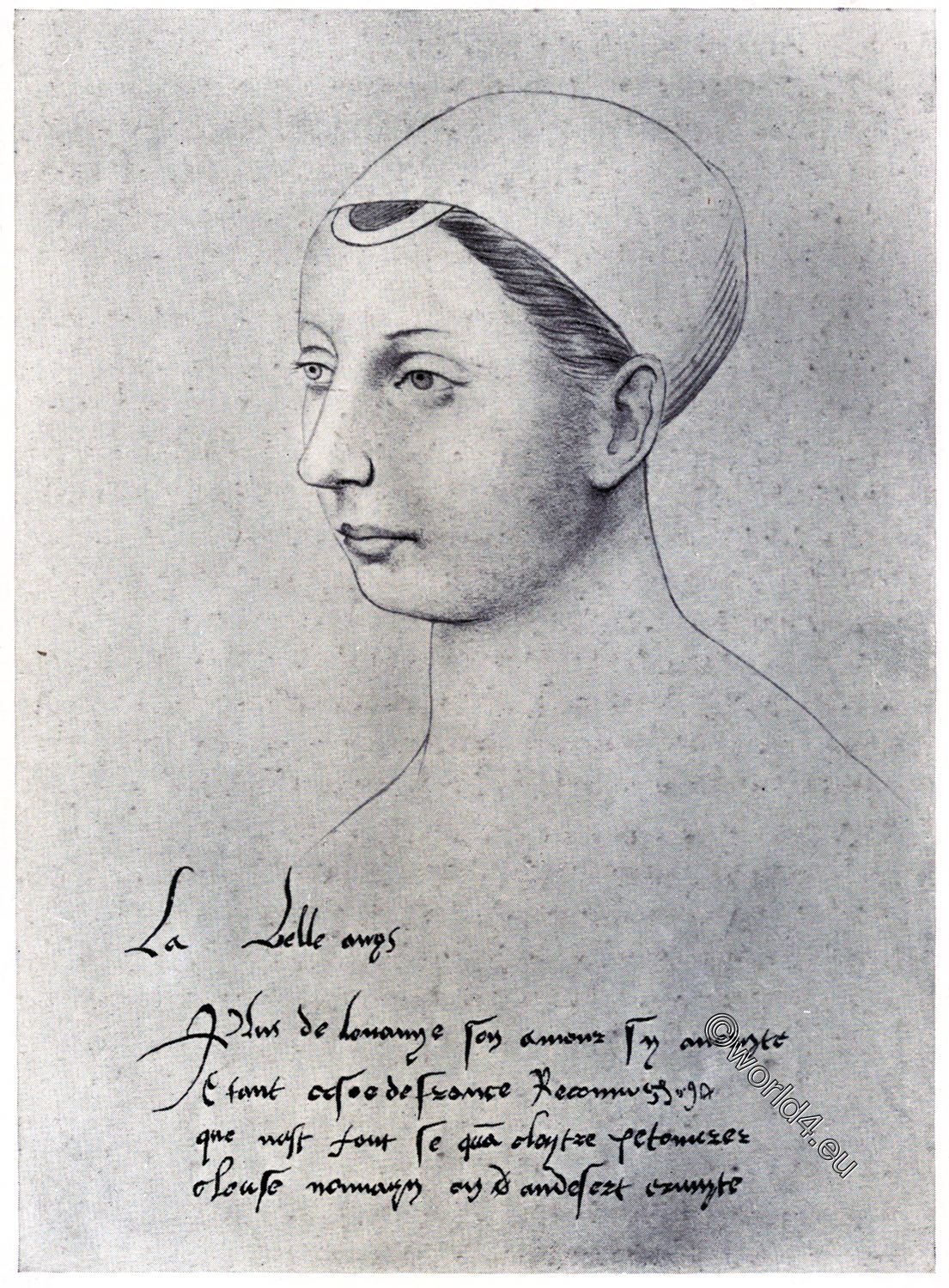

Agnes Sorel

The beautiful Agnes Sorel (1422-1450, known by the sobriquet Dame de beauté, was a favourite mistress of King Charles VII) was as much devoted to splendor as Isabeau de Bavière. Certain changes began to take place in women’s dress. Trailing gowns, high head-dresses in great variety, splendid stuffs, lace, gloves, mittens, rings, and necklaces, towards the middle of the fifteenth century; and with sundry additions of a still more extravagant nature with conical hats of which our Cauchoises have retained the shape, and the “coiffe adournèe,” a cylinder or tube diminishing in size towards the top, where it either terminated in a Rat crown, or curved over towards the back and hung down like a veil.

Agnes Sorel, famous both for wit and beauty, acted as it were the part of a queen. All women were led by her in the matter of dress, and this brilliant creature, surnamed the “Lady of Beauty,” began to adorn herself in the most magnificent costumes. If we may believe a chronicler of those times, her “train was a third longer than that of any princess in the kingdom, her head-gear higher, her gowns more numerous and costly,” and her bosom bare to the waist.

She is thus represented by a painter of the time, whose portrait of her may be seen in the Historical Gallery of Versailles. The fashions introduced by the “Lady of Beauty,” were indecorous in other respects besides that of uncovering the shoulders. Display became excessive under her auspices; she was the first to wear diamonds in the hair, and it is said also that she first endeavoured to get them cut with facets. Her heavy and splendid diamond necklace she called “my carcan.”

Isabelle de Portugal

Isabelle de Portugal wore a necklace from which hung a locket. The necklace was of pearls strung on gold thread. In the fifteenth century the scarlet coat of a duke or baron cost twenty livres the ell. Two ells and a half were necessary for a very sumptuous coat, which therefore cost 1000 francs; it lasted however for several years. Cloth of gold cost ninety livres the ell (1800 francs).

This gives us some idea of the cost of clothes in general. Women’s gowns required a greater quantity of material, because of their greater length. A lady who had neither page nor handmaiden to carry her train, was obliged to fold it across her arm. Certain dresses, “à quinze tuyaux” (or fifteen-fluted), fell in stiff tubes round the skirt, like the pipes of an organ. On horseback women wore shorter gowns, called “robes courtes à chevaucher.”

Many women of rank carried at that period light walking-sticks of valuable wood, with handles ornamented with the image of a bird. In place of mittens they wore violet-scented gloves, which were, according to Olivier de la Marche, imported from Spain. Towards the end of the fifteenth century, kid and silk gloves were in fashion, with gold and silver em broidery on the back. It was indecorous to give one’s hand gloved to anyone, or to wear gloves for dancing.

In France at the present time the contrary is our custom. Women made us of fans at church to disperse the flies. Their fans were ordinarily made of feathers, peacocks’ feathers in particular. The Queen of France astonished the Parisians by driving about among them in a swinging chariot of great splendour, that she had received as a present from the King of Hungary. For a long time she was the only woman in France who possessed such a vehicle. The court was beginning to decree official costumes of ceremony. Fashion had now founded her absolute rule.

During the whole of the Middle Ages fair hair alone was considered beautiful. On this point the French and the ancient Greeks were of one mind. Homer has described the fair hair of Aphrodite, Hera, and Pallas Athene; in like manner our ancient poets describe their heroines as blonde beauties, and they invented the word “blonder,” to become, or to grow fair-haired. This fashion must have led to the manufacture of enormous quantities of false hair.

Source: The HISTORY OF FASHION IN FRANCE; OR, THE DRESS OF WOMEN FROM THE GALLO-ROMAN PERIOD TO THE PRESENT TIME, FROM THE FRENCH OF M. AUGUSTIN CHALLAMEL. by Mrs. CASHEL HOEY and Mr. JOHN LILLIE.

Related

Discover more from World4 Costume Culture History

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.